Laura-Maija Hero, Saija Sokka & Jari Jussila

University-industry collaboration has been widely perceived as a tool for enhancing European innovation capacity (Ankrah and AL-Tabbaa 2015). The task of universities of applied sciences (UAS) is, in addition to the tasks related to learning, to carry out applied research and development work that supports working-life and regional development and considers the economic structure of the region. Universities of applied sciences are shifting their pedagogies to support this mission and to ensure the innovation competence development of the students via multidisciplinary innovation pedagogy (Hero and Lindfors 2019; Keinänen and Butter 2018).

Design-based education (DBE) is an umbrella term for student-centered, challenge-based, and multidisciplinary pedagogies that are based on the co-creation of new concrete solutions in collaboration with companies, students, teachers, and end-users. It is a “team-as-learner” approach to solving complex and ill-defined problems of companies and a rapidly changing world (Geitz et al. 2023; Guaman-Quintanilla et al. 2023). A paradigm shift to DBE calls for new types of pedagogical innovation management strategies in UASs.

Pedagogical innovation management

Applied science universities often serve as incubators for innovation, providing a supportive environment for students and teachers to collaborate with companies on design and innovation projects that can lead to groundbreaking usable solutions (Heikkinen and Isomöttönen 2015; Hero and Lindfors 2019; Keinänen and Butter 2018). This process not only contributes to the academic community and student learning but also has the potential to influence local economies, industry practices, and societal advancement.

Managing university-industry collaborative innovation efficiently is essential for successful innovation outcomes (Li et al. 2018). Effective innovation management within universities can catalyze change, driving progress and fostering a culture of continuous improvement and learning. Fostering an innovation climate and enhancing personal motivation among university students and teachers can significantly impact their innovative behavior (Newman et al. 2020). Management may increase the teacher’s motivation to engage in cooperation outside the UAS environment (cf. Joensuu-Salo et al. 2023).

Pedagogical management focuses especially on the management of teaching activities but can also be understood as a way of leadership action, and as creating conditions for cooperation and professional development (Bryman 2007; Ramsden et al. 2007). Pedagogical management is an activity that includes guidance, personnel development, and curriculum work, which also aims at developing learning in the community. Collegial and positive leadership perceptions have positive effects on the quality of teaching and learning (Ramsden et al. 2007).

Pedagogical leadership is known to be connected to high-quality teaching, the well-being and learning of teachers and students, and development and innovation. (Toom and Pyhältö 2020.) Pedagogical leaders are required to have a deep understanding of the core pedagogical processes, for example, collaborative curriculum work following the vision and strategy (Toom and Pyhältö 2020; Mäki 2022.)

Addressing the pedagogical innovation management challenge

This paper aims to address the innovation management challenge while Häme university of applied science (HAMK) is making a radical shift to design-based pedagogy in all its bachelor’s degrees. DBE (Design-based education ) in HAMK is the core of pedagogical strategy that is planned to be implemented in all degree programs starting from bachelors’ degrees. HAMK DBE is composed of eight dimensions (Figure 1).

In HAMK DBE, design thinking promotes the co-creation of solutions that are desirable, sustainable, viable, and feasible (Geitz et al. 2023; Jussila et al. 2020). Multidisciplinary collaboration is also perceived as an important element as innovations are often born at the border zones of professional fields, and because multidisciplinary teams are perceived as more creative than unidisciplinary teams (Hero & Lindfors 2019).

Solving authentic working-life challenges in multidisciplinary teams can be motivating, but at the same time can cause frustration and be stressful for the participants (Dindler et al. 2016), therefore it is important to also develop the well-being skills of both students and teachers involved in the innovation projects. Conducting such innovation projects can lead to the development of innovation competencies and promote both research-based and transformative approaches to solving problems (Jussila et al. 2023).

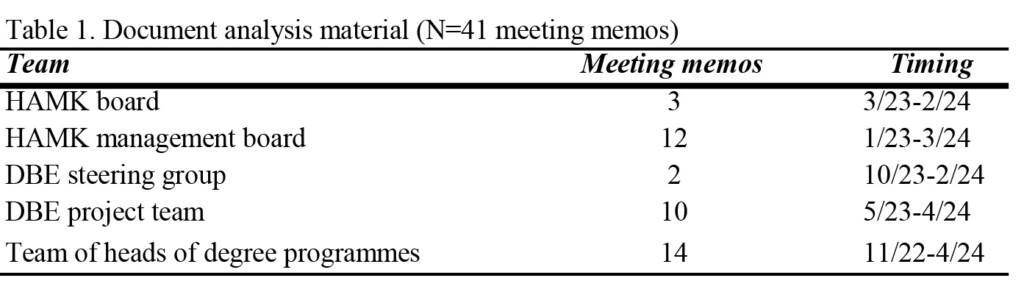

The role of the management staff in a DBE-based university of applied sciences (UAS) is very different from that in science universities. Who are the stakeholders in pedagogical innovation management that optimally support DBE and where should these management resources focus? For this purpose, we have conducted a preliminary stakeholder mapping, and two focus group workshops to unfold how teachers see DBE should be managed. The stakeholder mapping was conducted via a document analysis of 41 meeting memos (Table 1).

We conducted two co-design type focus group workshops.The workshops aimed to understand how teachers see the possible changes DBE brings to their teaching and what kind of support they would need from the management. The first one involved 23 and the second 38 UAS teachers. The material consists of 61 UAS teachers’ collaborative written input in the workshops. Data-driven content analysis (Krippendorff 2013) was conducted by first reading the written workshop material two times and then starting to encode the content piece by piece to identify themes according to the content.

Current innovation management stakeholders

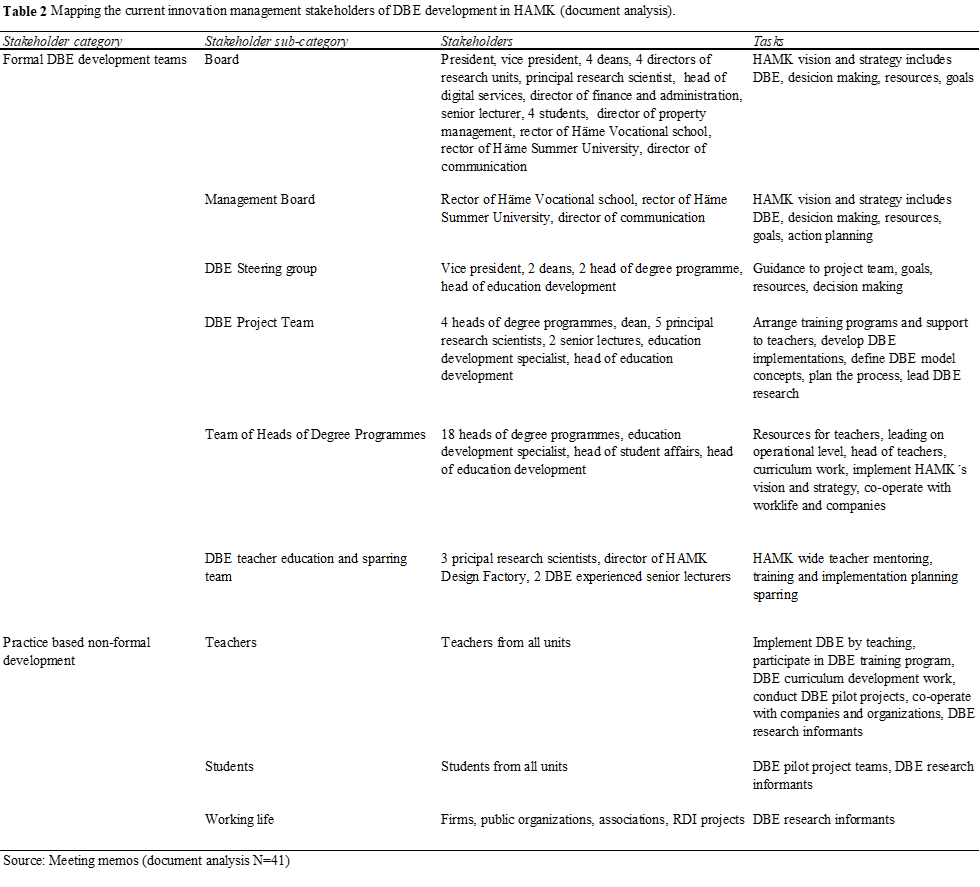

In this development phase of HAMK DBE, there are designated development teams and indirect development participants (Table 2).

The formal DBE development teams are the Board, Management Board, DBE steering group, DBE Project Team, Team of Heads of Degree Programmes, DBE teacher education and sparring team. Practice-based non-formal development stakeholders are teachers, students, and companies and organizations.

Teachers’ views and needs affect pedagogical innovation management

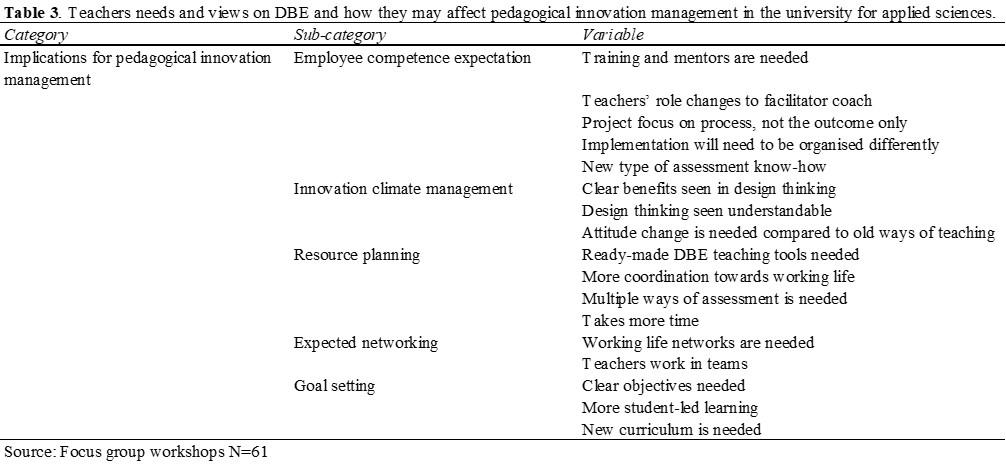

Teachers expect many changes in their teaching. These changes may affect how they need to be managed (Table 3).

These teachers’ statements have implications for management planning and practical actions, as well as for employee competence development. As the role of the teachers changes in DBE, teachers need to be supported. The focus of training should be on the teacher’s practical role-taking and implementation planning, pedagogical alignment and assessment, and concrete pedagogical tools for this type of multidisciplinary and open challenge-based learning. Innovation climate management may become easier, as the teachers see clear benefits in design thinking. Teachers seem to learn quite easily at least the theoretical design thinking principles. However, teachers see that an attitude change is needed from all teachers compared to the old ways of teaching. (Teacher focus group workshops).

As the teachers have more time-consuming coordination with other teachers and the working-life networks, they feel they need more hours in their work plans, especially in the collaborative planning phase. However, based on this study, teacher collaboration and sharing of resources might save some hours as the work is shared with several teachers. Teachers are expected to have working-life networks. Teachers are not teaching alone in their classrooms. They work together with organizations to develop the best possible outcomes with students for the benefit of the companies while still facilitating student learning. Formulating the job description and setting goals for the teacher may need to be re-evaluated as the teachers feel they need clearer objectives and new curricula to guide the DBE teaching (Teacher focus group workshops).

Pedagogical innovation management actions

The shift to DBE pedagogy involves several levels of management from the top management board to heads of degree programs, researchers, teachers, students, and companies and organizations. There have been implications for pedagogical innovation management. The management of a UAS should focus on many change dimensions at the same time. Those include transparent employee competence expectations, innovation climate management, resource planning, expected networking of the pedagogical staff, and clear DBE goal setting.

It has been possible to focus and develop pedagogical innovation management actions already in three ways based on pilots and research (e.g. Hero et al. 2024).

Firstly, pedagogical structures have been developed:

- A mentor system is established. Every campus will have two DBE mentors to support and give support and innovative ideas to other teachers.

- DBE is integrated to curriculums by offering a curriculum and implementation guide and learning targets to degree programs.

- Integrated DBE steering group and DBE project team will continue to monitor and develop DBE. This group makes decisions and definitions of policy on how to develop and advance DBE in HAMK.

- A DBE research team has started working and collecting data. 5) 11 DBE pilot projects have been studied from student, teacher, and working-life perspectives.

Secondly, pedagogical support has been organized

- Trainings for teachers and staff have been offered online and offline. Some of the staff have already participated in ”DBE Dip Day” to try out DBE.

- Design thinking toolbox has been offered to teachers and DBE student teams.

- Guidance has been offered for teachers on the practical implementation of DBE study modules. A DBE Teachers’ Moodle repository has been opened.

- A guidebook and assessment playing cards have been offered (Hero 2024).

Thirdly, working life integration management has started.

- A DBE agreement template has been reformed.

- An open challenge negotiation template and a DBE working-life collaboration training for teachers have been piloted.

- A survey and interview guide for collecting information about the impact of DBE has been developed and the pilot companies have been interviewed to develop DBE together with companies and organizations.

It is possible to pilot study pedagogical management. Based on our findings, a systematic research-based approach to pedagogical innovation management is essential in larger and wider pedagogical paradigm changes.

Authors

Laura-Maija Hero, (D. Ed), Principal research scientist, HAMK Häme University of Applied Sciences, laura-maija.hero(at)hamk.fi

Saija Sokka, (M.A. Ed.), Head of Education Development, HAMK Häme University of Applied Sciences, saija.sokka(at)hamk.fi

Jari Jussila, (D.Sc), Principal research scientist, Director, Hamk Design Factory, HAMK Häme University of Applied Sciences, jari.jussila(at)hamk.fi

References

Ankrah, S. and AL-Tabbaa, O. (2015). Universities–industry collaboration: A systematic review. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 31(3), pp.387–408. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scaman.2015.02.003.

Design-based education (DBE). Design-based education (DBE) is the starting point for learning and teaching at HAMK. Available at: https://www.hamk.fi/en/about-hamk/strategy/design-based-education-dbe/. [20.2.2025].

Dindler, C., Eriksson, E. and Dalsgaard, P., 2016. A large-scale design thinking project seen from the perspective of participants. In: Proceedings of the 9th Nordic Conference on Human-Computer Interaction. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1145/2971485.2971559.

Geitz, G., Donker, A. & Parpala, A., 2023. Studying in an innovative teaching-learning environment: Design-based education at a university of applied sciences. Learning Environments Research, pp.1-19. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10984-023-09467-9.

Guaman-Quintanilla, S., Everaert, P., Chiluiza, K. & Valcke, M., 2023. Impact of design thinking in higher education: A multi-actor perspective on problem solving and creativity. International Journal of Technology and Design Education, 33(1), pp. 217-234. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10798-021-09724-z.

Heikkinen, J. and Isomöttönen, V., 2015. Learning Mechanisms in Multidisciplinary Teamwork with Real Customers and Open-Ended Problems. European Journal of Engineering Education, 40(6), pp.653-670. Available at: https://doi:10.1080/03043797.2014.1001818.

Hero, L.-M. (2024). InnoCards 2.0 DBE: Innovation competence in a multidisciplinary team in design-based education. Publications of Häme University for applied sciences. Available at: https://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-951-784-848-0.

Hero, L.-M. and Lindfors, E., 2019. Students’ learning experience in a multidisciplinary innovation project. Education + Training, 61(4), pp. 500-522. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1108/ET-06-2018-0138.

Hero, L.-M.; Galiot, R.; Jussila, J. & Sokka, S. (2024). Becoming a DBE teacher. Teachers’ understanding and needs at the beginning of the transition to design-based education. Hamk Unlimited Scientific 13.6.2024. Available at: https://urn.fi/URN:NBN:fi-fe2024060342971.

Joensuu-Salo, S., Peltonen, K. and Hämäläinen, M., 2023. The importance of HEI managerial practices in teachers’ competence in implementing entrepreneurship education: Evidence from Finland. International Journal of Management Education, 21(2), p.100767.

Jussila, J., Raitanen, J., Partanen, A., Tuomela, V., Siipola, V. and Kunnari, I., 2020. Rapid product development in university-industry collaboration: Case study of a Smart Design Project. Technology Innovation Management Review, 10(3), pp. 49-59. Available at: http://doi.org/10.22215/timreview/1336.

Jussila, J., Räty, M. and Siintoharju, S.-M., 2023. Developing students’ transversal skills: A case study of an international product development project. CERN IdeaSquare Journal of Experimental Innovation, 7(3), pp. 32-37. Available at: https://doi.org/10.23726/cij.2023.1474.

Keinänen, M. and Butter, R., 2018. Applying a self-assessment tool to enhance personalized development of students’ innovation competencies in the context of university-company cooperation. Journal of University Pedagogy, 2(1), pp.18-28.

Krippendorff, K., 2019. Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology (4th ed.). Sage.

Li, F., Chen, J. and Su, Y., 2018. Managing the university-industry collaborative innovation in China. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 31(1), pp. 62-82. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1108/jocm-04-2017-0148.

Mäki, K. 2022. Pedagoginen johtaminen – korkeakoulun johtajan työ vai yhteisön tapa toimia? [Pedagogical management – the work of a university director or the community’s way of working?], 214–224. In Mäki, K. & Vanhanen-Nuutinen, L. 2022. Korkeakoulupedagogiikka – ajat, paikat ja tulkinnat. Haaga-Helian julkaisut 7/2022. Available at: https://www.theseus.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/756306/HH_korkeakoulupedagogiikka_screen_sis.pdf?sequence=1 [15.4.2024].

Newman, A., Round, H., Wang, S. and Mount, M., 2020. Innovation climate: A systematic review of the literature and agenda for future research. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 93(1), pp.73-109.

Ramsden, P., Prosser, M., Trigwell, K. and Martin, E., 2007. University teachers’ experiences of academic leadership and their approaches to teaching. Learning and Instruction, 17, pp.140–155.

Toom, A. and Pyhältö, K., 2020. Kestävää korkeakoulutusta ja opiskelijoiden oppimista rakentamassa [Building sustainable higher education and student learning]. Opetus- ja kulttuuriministeriön julkaisuja [Publications of the Ministry of Education and Culture], 2020:1. Available at: https://julkaisut.valtioneuvosto.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/161992/OKM_2020_1.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y [11.4.2024].