Filip Levälahti & Carina Kiukas

How can central elements in the European framework for higher education (HE) pedagogy, such as student-centered learning approaches and self-directed learning to promote students’ learning experience, become concrete in a project about skills tracking as a digital solution? This is the question that was raised in the Erasmus+ financed project Skills tracking as a digital solution for student-centred learning (SkillTrack) carried out by four partner universities; Arcada University of Applied Sciences (Finland), Başkent University (Turkey) and Evangelische Hochschule Ludwigsburg, (Germany) and Rīga Stradiņš University (Latvia).

The overall aim of the project is to use a skill tracking system as a tool to promote an evidence-based discussion between public administrations, educational institutions and employers and facilitate dialogue to align study outcomes with the needs of the labour market to reduce skills mismatch. As a complementing frame to the skills tracking system our aim was to developed a guide to support re-thinking pedagogical approaches and developing mindsets among teachers and students rather than giving practical tips.

Theoretical framework

The student-centered learning approach stresses the importance of focusing on the student, his/her learning and preparing a supportive learning context to foster a deeper learning process (Taylor 2013; Wulf 2019). With learning context, we include everything that has an impact on student’s learning process, such as learning goals, assessment, learning strategies, resources, learning environment, support, workload, social presence, learning activities, etc.

The learning process is most efficient when learners can engage in and make sense of their learning. To be successful in a student-centered approach, we must support students to be an integral part of the academic community (The European Student Union 2010; Hoidn & Klemenčič 2020). This means that we need a holistic approach to the whole learning process. To make this possible, we started the process of creating the guide based on self-regulated learning (Zimmerman & Campillo, 2002). But we realized to get a broader overview we also had to look at theoretical aspects of self-direction, self-efficacy, and self-reflection.

The definition we used for self-regulated is Zimmerman’s definition, “The degree to which students are metacognitively, motivationally and behaviorally active participants in their own learning processes” (Mentz et al. 2019). For the student, this means implementing strategies and utilizing the learning context to reach the set goals.

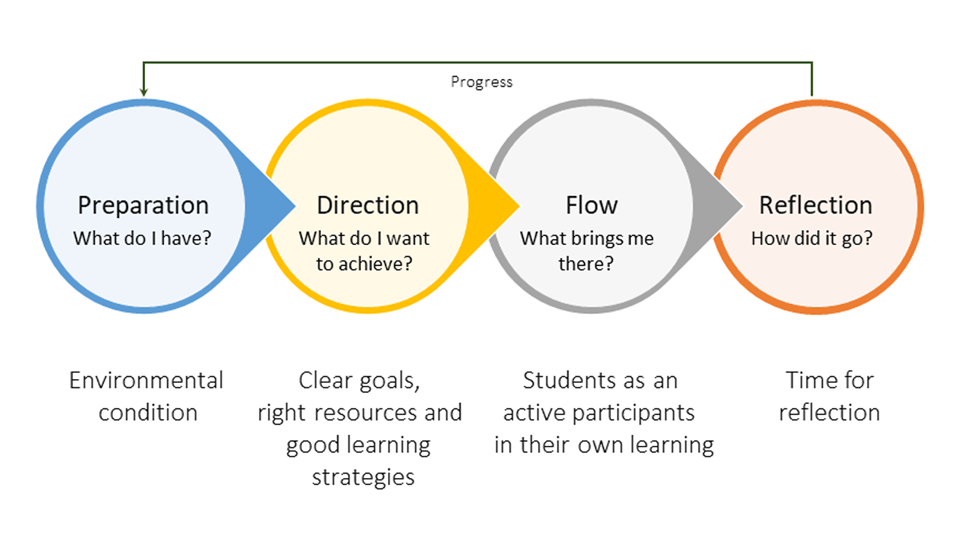

This can be done by first preparing the students for a learning session and thereby helping them to find the motivation to learn (preparation). Secondly supporting students’ independence in finding their own strategies and responsibility for learning and acting on it (direction and flow). Finally, we need to keep the students reflecting on their own learning (reflection).

Even if there are similarities in the terms self-directed and self-regulated we used both to distinguish between the students’ freedom to plan and choose learning goals and paths and take control of their own learning (self-directed) and the ability to carry out their plans (self-regulated).

In the guide we used Mentz et al. (2019, p. 40) definition of self-directed learning; “Self-directed learning may then be defined as a situation in which (a) the individual is able to define his or her own goals, (b) the goals are related to his or her central needs or values, (c) the individual is able to define the paths (i.e., procedures, strategies, resources) to these goals, and (d) the achievement of these goals represents a realistic level of aspiration for the individual, that is, not too high or too low, but high enough to be challenging.”.

The main idea is for the students to take ownership of the learning process and set up goals and strategies. These can also be created by peers where a group of students defines their own goals and strategy.

Before a learning session the student will ask questions like am I capable of accomplishing this task, is it worth the effort, what do I get out of this, etc. By taking into consideration both students’ values and expectations we can motivate students to engage in a learning process (Ambrose et al. 2010). Also, by supporting the student’s self-efficacy we can create a better foundation for self-directed learning. According to Bandura (1997) self-efficacy “refers to beliefs in one’s capabilities to organize and execute the course of action required to produce given attainment”. We cannot always affect the student’s personal factors, but we can prepare the context where the student will work.

Self-reflection includes both reflecting on the achieved knowledge and skills and on the process of reaching them (Mentz 2019). A well-prepared learning context will support the student’s self-regulated learning. Reflecting on what has been working well and what could improve is a part of the learning process and makes an impact on the progression.

Pedagogical guide

The guide is primally aimed at teachers. But students could also benefit much from taking part in the guide for more understanding of their own learning performances. Interaction and collaboration between learner and teachers and between peers are important in student-centered and self-directed learning. This means that students should be involved (more or less) in all elements in this guide.

The four phases in the model (see figure 1) should be read as building blocks rather than a time sequence. It highlights the importance of building on the foundation and preparing the learning context to make self-regulated learning happen. The phases are all, more or less, active throughout the learning process. Both the teacher’s and student’s role might change during the process. In the beginning, the focus is more on the design (learning goals and strategies), while it is later more about applying the set strategies. Ideally, the students are active during the full process and are more self-directed during the application process.

The first phase, preparation, is about strengthening students’ agency and control over their own learning. This requires that teachers prepare the students and learning context for self-directed learning. The learning context needs to be prepared, transparent, and visible. Involving the student early in this process will increase his/her motivation and smoother self-directed learning. This preparation will also support the student’s self-efficacy and motivation.

Direction is about the student taking ownership of their own learning. An introduction and counseling discussion with the students should include defining goals – The student will be supported in defining his or her own goals. These goals are based on the expressed learning outcomes for a learning session. It is also important that the student can relate the expected learning outcomes to his or her central needs or values. The introduction should also include to define learning path – the student will also be supported in defining the paths (i.e., procedures, strategies, resources) to reach these goals. Also provide the students with some flexibility and a feeling of ownership. Finally, an introduction should include the process of defining realistic level of performance – the student will be supported to decide his or her level of performance that he or she would like to achieve according to the set level in the defined learning outcomes?

With flow the students, not only own their learning, but also master and engage in their own learning process. It is about reaching set goals and strategies by engaging in different learning activities. Good preparation of both the learning context and the student will support the flow. It is also important to maintain a metacognitive reflection during the activities and adjust the learning if needed.

This learning process will develop both students’ intended skills and their learning competence. The reflection part of this process is not only important for evaluating if students have reached their goals but also to give the opportunity to correct misunderstandings and further develop their skills. It is also an important phase to evaluate their own learning processes.

Conclusions

Our experience is that we regularly but at times with little reflection, claim to use concepts such as student-centered learning and self-directed learning. Achieving the great ambitions of these concepts requires constant reflection in the contexts in which we act. Teachers need to reflect on the work they do to support students’ learning. Students need to be given counselling and structures that enable them to be active in their own learning process.

With the pedagogical guide for student-centred and self-directed learning we strived to promote an international pedagogical discussion within the project. The guide will be tried out and further developed based on the experiences in the four partner universities during the project. Workshops for reflections on the implementation of the model will be held in every partner university. The importance of reflecting repeatedly on how we make student-centered and self-directed learning happen needs to be supported not only in our project. The guide will hopefully also support colleges outside the project.

Filip Levälahti, M. Ed., E-learning specialist, Arcada UAS, filip.levalahti(at)arcada.fi

Carina Kiukas, PhD Adult Education, Dean, School of Engineering, Culture and Wellbeing, Arcada UAS, carina.kiukas(at)arcada.fi

References

Ambrose, S., Bridges, M., DiPietro, M., Lovett, M., & Norman, M. (2010). How Learning Works (1st ed.). Wiley. https://www.perlego.com/book/1008816/how-learning-works-pdf, p. 70

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. W H Freeman/Times Books/ Henry Holt & Co.

Hoidn, S., & Klemenčič, M. (Eds.). (2020). The Routledge international handbook of student-centred learning and teaching in higher education. Routledge.

Mentz, E., De Beer, J. & Bailey, R. (eds.), 2019, ‘Self-Directed Learning for the 21st Century: Implications for Higher Education’, in NWU Self-Directed Learning Series Volume 1, pp. i-436, AOSIS, Cape Town. https://doi.org/10.4102/aosis.2019.BK134

The European Student Union, 2010. Student Centered Learning. An Insight Into Theory And Practice External) https://docplayer.net/7231327-Student-centered-learning-an-insight-into-theory-and-practice.html

Taylor, J. A. (2013). What is student centredness and is it enough? International Journal of the First Year in Higher Education, 4(2), 39-48.

Wulf, C. (2019). “From Teaching to Learning”: Characteristics and Challenges of a Student-Centered Learning Culture. In Inquiry-based learning–Undergraduate research (pp. 47-55). Springer, Cham.

Zimmerman, B.J. & Campillo, M. (2002). Motivating self-regulated problem solvers. In Davidson, J.E. & Sternberg, R.J. (Eds.), The nature of problem solving. New York: Cambridge University Press.