Authors: Marja Laurikainen & Irma Kunnari.

Abstract

Rapid changes in the world of work due to globalization and digitalization have transformed higher education and students’ lifelong learning, career management skills and digital competences have become more important. These skills and competences need to be strengthened in authentic settings by engaging students and making their evidence of competences transparent with ePortfolios. In this paper, the authors describe and summarize research done in five European countries and six higher education institutions on three different perspectives (student, employer, teacher) on ePortfolios. The results show that the benefits of ePortfolios need to be made clear for students and the use of ePortfolios needs to be embedded into curriculum to make it systematic and meaningful, not just some extra work. This requires new kind of collaboration between teachers but also students need to take ownership of their learning process and involve other stakeholders to their assessment, i.e. peers, representatives from the world of work. Nonetheless, from the employer interviews it is evident that ePortfolios, if done properly and with thought, can make competences and skills more visible and thus, create better matches in the recruitment processes.

Introduction and theoretical background

The critical points of the quality of learning in competence-based education are the assessment and guidance practices. However, if competence assessment is done by using traditional methods in individual basis and within the school environment, it fails to both motivate the students and to create constructive alignment of the desired competences (Biggs & Tang 2007). In addition, the assessment practices should support the development of competence-based education (Koenen, Dochy, & Berghmans 2015) as well as the 21st century skills (Voogt et al. 2013), which are crucial in the rapidly changing world of work. The globalization and digitalization have transformed studying and working environments, and students’ lifelong learning, career management skills and digital competences need to be strengthened by engaging students to be more involved in their own learning and assessment processes in higher education.

Inspiring assessment and guidance practices, like peer assessment, collaborative digital assessment, and creating evidence of competences in real life settings are still not comprehensively used in higher education (e.g. Medland 2016). Further, the use of multimodal assessments seems to be limited (Connor 2012). Creativity and innovation are needed to under-stand what the evidence of competences is in real life settings and how students can document and make their skills transparent with digital tools. The need to have a digital professional profile has been recognized, but it is evident that there is still a lack of guidance and skills to create that, both from the students’ and teachers’ point of view.

Digital portfolios have a dual meaning – they can be used as a workspace for learning and reflection process making it more transparent and inspiring, and as a showcase being the inventory of all evidence/artifacts of skills and competences (Barrett 2010). With ePortfolios, assessment is not just assessment of learning or assessment for learning, but also assessment as learning. Thus, ePortfolios are used in self and peer assessing, giving feedback, co-creating evidence of competences in shared platforms and utilizing different digital applications. This is likely to increase the students’ feeling of competence, relatedness and autonomy, which are fundamental for creating motivation and wellbeing in learning (Kunnari & Lipponen 2010; Ryan & Deci 2000). In addition, ePortfolio as a story and positive digital identity development (branding) enables students’ choice and personalization, further helping them to find their voice and passions (Friedman 2006).

In this paper, the authors analyze all the data and outcomes collected from one case study (Yin 2009) in “Empowering Eportfolio Process (EEP)” research and development project funded by the European Union, where five European countries (FI, DK, BE, PT, IE) and altogether six higher education institutes (HEIs) participated. Based on the research done in the project, this paper aims to establish a common understanding of ePortfolios and find out what the key elements and challenges in the process of using ePortfolios in higher education are. Not only that, but also how to develop the use of ePortfolios to empower and motivate students in their own learning process and how to improve their employability, and skills related to that. Thus, in this case ePortfolios and the learning and assessment processes related to them are investigated from three different perspectives (student, employer, teacher/educational institution) in order to find elements to empower and engage students.

In the framework of this paper, the authors understand ePortfolios based on the following definition of ePortfolios:

“ePortfolios are student-owned digital working and learning spaces for collecting, creating, sharing, collaborating, reflecting learning and competences, as well as storing assessment and evaluation. They are platforms for students to follow and be engaged in their personal and career development, and actively interact with learning communities and different stakeholders of the learning process.” (Kunnari & Laurikainen 2017.)

This definition highlights the dynamic nature of ePortfolios and students’ ownership, but also how connected the creation of them is to other stakeholders. To develop the use of ePortfolios it was needed to hear all the voices, students’ and teachers’, but also to study and raise the awareness in the world of work. In the current labor market, finding open positions and jobs as well as the recruitment processes are evolving through digitalization. Social networking and online presence help to connect with potential employers, and companies are increasingly following potential employees’ online presence. Indeed, there are less traditional résumés, virtual ePortfolios or résumés are easy to build (technically) and manage because one can access them from anywhere and anytime (Forbes 2011).

The aims of the research of three perspectives on ePortfolio are described below. The methodological approaches in all three are presented in the chapter Methodology.

The aim of the research done on students’ ePortfolio process was to investigate the assessment and guidance processes as well as ePortfolio environments and tools available in participating countries. In addition, the career learning and motivating or engaging aspects of the process were investigated. Ultimately, the research aimed to give an understanding on how students’ competences versus assessment practices are constructively aligned in order to create empowerment for students and what kind of tools can support this the most efficient way.

The research on employers’ perspective aimed to reveal how students’ competences and the needs of the world of work meet. In addition, it aimed to find out what kind of digital portfolios the representatives of various organizations want to see when they are recruiting a new employee and the specific things they assess from the (digital) portfolio. Educational institutions are only starting to understand the meaning of ePortfolios or online presence. Thus, educational processes do not yet fully support the building of the skills and competences needed for this new kind of job hunting. The research on employers’ expectations on digital portfolios was made to improve the ePortfolio process within educational institutions as well as to raise the awareness of employers of the benefits of ePortfolios.

The third and final research aimed to investigate teachers’ guidance processes related to ePortfolios and how ePortfolios are implemented in different participating HEIs. Further, it aimed to describe how ePortfolio processes are integrated into curriculum and how sustainable those processes are, how the assessment processes are organized, and what the structures for good utilization of ePortfolios in the learning infrastructure are.

Methodology

The data for this article was collected from one case study (Yin, 2009) “Empowering Eportfolio Process (EEP)” research and development project where five European countries (FI, DK, BE, PT, IE) and altogether six higher education institutes (HEIs) participated. All of the HEIs are in different stages of implementing ePortfolios and use them in very different contexts. Two of the HEIs represent initial teacher training, one HEI is starting to integrate ePortfolios in the context of health and welfare education. On the other hand, one HEI focuses on the aspects of adult/continuing education, career guidance and recognition of prior learning, and one HEI represents the point of view of an educational development unit, which promotes the quality of academic education and supports continuing education and other forms of lifelong learning. In addition, one HEI represents both professional teacher training and bachelor level education, in this case especially in the fields of business administration and bioeconomy.

The research was done by teams of 1‒4 researchers who are experienced in different aspects of educational development (digital, pedagogical and curriculum development) as well as implementation of ePortfolios in higher education. The research was conducted between autumn 2016 and spring 2018 in the participating HEIs. During this time, the research teams communicated and collaborated through digital platforms as well as meetings in events on ePortfolios (seminars) which provided opportunities to discuss the findings and draw up common recommendations.

Data was collected in a small-scale field research on three perspectives of the ePortfolio process – from students’, employers’ and teachers’/higher education institutes’ point of view. Firstly, a desk research was made to map the current situation related to national policies, strategies and recommendations, existing practices and models in participating HEIs (and beyond) related to ePortfolios. These were collected into a digital publication “Collection of Engaging Practices in ePortfolio Process” (Kunnari & Laurikainen 2017), which was a starting point for the research on the three perspectives.

For all three studies, there was a unified framework for data collection and analyzing. However, the data collection in each country was implemented in a way that served the purposes and specific circumstances of that specific HEI and country the best possible way. Thus, the methods (e.g. surveys, interviews, literature research, and focus groups) and samples vary but still follow the same overall framework. In addition, in all HEIs participating in this research there were internal pilot activities, which fed data collection and analyzing process.

Methods in investigating students’ perspective

Due to different stages and situations in ePortfolio implementation in each country and participating HEI, the samples used to this research vary in size, degree programme, degree cycle and phase of the studies. The average size of the sample was n=19 and mainly from BA level students. The average response percentage was 35. The country specific information is provided in Table 1.

Table 1. The sample used to investigate students’ perspective on ePortfolios(Kunnari, Laurikainen, & Torseke 2017; Korhonen, Ruhalahti, & Torseke 2017; Poulsen & Dimsits 2017; Devaere, Martens & Van den Bergh 2017; Van Eylen, & Deketelaere 2018; Pires, Rodrigues & Pessoa 2018; Choistealbha 2018).

| FINLAND | DENMARK | BELGIUM 1 | BELGIUM 2 | PORTUGAL | IRELAND | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ePortfolio stage: emerging/ existing | Existing in some programmes and teacher training, Emerging in others | Existing but only in the application/ entrance phase | Existing/ Emerging | Emerging | Existing in some courses/ programmes | Existing |

| Sample | ||||||

| Number of students | n=18 (10 BA, 8 Teacher training students) | n=15 | n=13 | n=18 | n=16 (13 for interviews, 3 for narratives) | n=32 |

| Study programmes | Sustainable Development & Professional Teacher Training | Digital technologies in VET-programmes | Medical School | Medical Laboratory Technology (MLT) | Different programmes, diversity of profiles (criteria of having been in learning situation using digital media in the previous school year or being enrolled in different courses at IPS | Education Studies |

| Bachelor/Master/PhD/ continuing education/ other | BA & Professional Teacher Training | Continuing education/adult education | Two BA groups, 1 MA group | BA | BA/MA | BA |

| Study year | 2nd year (BA), 1-year teacher students | Three classes of the same programme, two classes completed in autumn 2016 and one in sprint 2017 | Three different student groups; | 3rd year | three groups of students for interviews (diverse profiles), three Master students for narrative writing | 1st to 4th grade, During work placement – i.e. when they were beginning to utilise the ePortfolio |

| Response rate | N/A, targeted survey | 33% (15 /48 respondents) | 46% (6/20 BA; 7/8 MA) | 35% (18/52) | N/A, targeted survey | 27% (32/120) |

For investigating the students’ perspectives on ePortfolios there was a co-designed overall structure of themes and questions that was used in each participating country, however, the methods were applied based on the situation in each country. The common framework included four themes: 1) Students’ experiences and perspectives on ePortfolios, 2) Identification of the personal dimensions that facilitate students’ engagement in the ePortfolio process, 3) General competences and digital competences developed by students in the ePortfolio process (example: European Commission Framework, 2016: e.g. information and data literacy; communication and collaboration; digital content creation; safety and problem solving), and 4) The learning environments and organizational dimensions that support students in the ePortfolio process (engaging contextual conditions).

The methods of data collection and analysis as well as the content of the study from each country are introduced in Table 2.

Table 2. The methodology used to investigate students’ perspective on ePortfolios(Kunnari, Laurikainen, & Torseke 2017; Korhonen, Ruhalahti, & Torseke 2017; Poulsen & Dimsits 2017; Devaere, Martens & Van den Bergh 2017; Van Eylen, & Deketelaere 2018; Pires, Rodrigues & Pessoa 2018; Choistealbha 2018)

| FINLAND | DENMARK | BELGIUM 1 | BELGIUM 2 | PORTUGAL | IRELAND | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Method | ||||||

| Qualitative/ quantitative | Qualitative | Qualitative | Qualitative | Qualitative | Qualitative | Quantitative/ qualitative |

| Tool | Online questionnaire to a student focus group (GoogleForm) | Online survey | Online questionnaire | Online questionnaire (LimeSurvey) | group interviews and narratives written by students | Online survey (SurveyMonkey) |

| Distribution channel | Filled in during guidance session | By email | By email | By email | Personal contact | |

| Content | ||||||

| Questions | Discussion of the common themes and their sub-questions described above; In addition, specific questions for teacher students about the role of ePortfolios in becoming professional teachers, user experiences, benefits/challenges while creating ePortfolios, support for facilitation, ePortfolios in assessment. | Ten open questions, statements on: challenges and possibilities of ePortfolio, competences needed to create an ePortfolio, definition of the concept “ePortfolio”. | Open questions; BAs experience of their nursing internship during 2015 and 2016 summer and their patientcare internship in December 2016; MAs had no previous experience in ePortfolios | Discussion of the common themes and their sub-questions described above | Discussion of the common themes and their sub-questions described above | The research question “What are students’ perspectives of the benefits and challenges of using ePortfolios?” guided the research: Discussion of the common themes and their sub-questions described above |

| Analysis | ||||||

| Method | Collected, compiled and analysed with the focus on emerging ePortfolio use and what needs to be addressed and taken into account | Focus on meaning-making, statements of the respondents’ about how to understand/make sense of ePortfolios (concept, learning space) | Driven by two aspects: collecting the broad variety of answers due to the exploratory focus of this study and the frequency of answers given | The responses were further outlined by frequency diagrams and by descriptive analysis | Qualitative content analysis | Thematically in line with the survey questions |

Methods in investigating employers’ perspective

The research was implemented in a case study format. Again, there was a common framework and themes to investigate through individual or group thematic interviews with employers, representatives of career services, recruitment companies and other organizations. The themes to discuss were existing recruitment settings, the benefit of ePortfolios in these processes and how employers see their role in supporting the creation of ePortfolios of students, what kind of mutually benefitting collaboration there could be.

There were altogether twelve diversified cases from the participating countries: Finland with five case studies, Denmark with one, Belgium with three, Portugal and Ireland with two cases each. The cases came from the field of medical services, education, universities’ alumni and career services, human resources and recruitment services, project coordination offices, creative industries and digital services.

Methods in investigating teachers’ perspective

The participating HEIs were asked to collect data from their organizations related to teachers’ guidance practices in the ePortfolio process, how they are implemented, is the process integrated into curriculum and how sustainable it is, how the assessment is organized and what the structures for good utilization of ePortfolios in the learning infrastructure are. The research teams in participating HEIs utilized existing materials, discussed them with teachers and others involved in ePortfolio process, and based on these, drew a framework image of their organizational context related to ePortfolios.

During a seminar in Belgium in February 2018, the research teams had a wider discussion on the similarities and differences between each HEI’s context, and based on the discussions they further developed their own frameworks. A consensus was reached that it is very challenging to describe one frame that fits all HEIs due to differences in e.g. structures, programmes and digital environments. However, each HEI can present their own framework and highlight the good practices in it and thus, there is a collection of good practices that others can utilize depending on their own context.

Results of the analysis on three perspectives on ePortfolios

The methods and results from the field research in five countries on three different ePortfolio perspectives (student, teacher, employer) were reported in a structured summary by the participating HEIs. In addition, the preliminary results were presented in poster sessions during three different seminars: in Portugal in March 2017, in Ireland in September 2017 and in Belgium in February 2018. A common qualitative analysis of the findings was made based on both the summaries and the poster sessions. The following three sub-parts describe the findings from each perspective.

Students’ ePortfolio process and development of digital competence

What is evident from this research is that the use of ePortfolios is still emerging only in these six participating HEIs. There are some good examples in singular courses and study programmes but in general, the understanding of ePortfolios is not sufficient, with both students and teachers.

The students had a general positive and engaged attitude towards the use of ePortfolios but the benefits were not completely clear nor the possibilities. They could see how ePortfolios can support their personal and professional development and give transparency to the learning process, which correspond to the previous study related to students’ adaptation to ePortfolios by Lopez-Fernandez (2009). However, this study demonstrated the diversity of students’ experiences related to the use of ePortfolios as well as different conceptions about the process and the tools: not all of them were familiar with the definition of ePortfolio and thus understood it in several different ways. Nonetheless, generally it was seen “as an online student-owned learning space, based on technological and digital tools, that can store and share their reflections, learning outcomes, achievements and evidence of competences, by using non-traditional resources — such as blogs, CV’s, web pages and LinkedIn profiles.” (Kunnari, Laurikainen, Pires & Rodrigues 2017).

The findings showed that two types of digital competences are needed in the ePortfolio process: in the creation of ePortfolio (technical) and in compiling the ePortfolio (editing). In addition, in order to create content for the ePortfolio, students need transferable skills (e.g. reflection, collaboration, communication, organization and visualization). The study also revealed that students perceive their digital competences from intermediate to high level; however, even though they may be competent in using digital tools and apps in their leisure time and socializing purposes, they may not be aware of digital solutions in the learning context. This means that before starting to use ePortfolios, they need preparation and support in their digital skills. (Kunnari, Laurikainen & Torseke 2017).

Another issue students emphasized is that ePortfolio creation and development need to be integrated into curriculum throughout the studies, i.e. there needs to be time allocated for this as well as other resources such as teachers’ guidance. Eportfolio should be in the core of the learning process in collaboration with peers, employers and other stakeholders.

Competence transparency and its innovativeness – Employers’ perspective

In participating HEIs’ contexts, ePortfolios are mainly used as a learning space during the studies where students collect evidence of their skills and competences and utilize self- and peer-assessment to reflect their own learning. In many cases, the connection to life after graduation, i.e. when seeking for an employment and/or further studies, was lacking or not very evident. This corresponds to a more general challenge in Europe, which the European Union has recognized in its modernization agendas i.e. the models and intensity of cooperation between universities and businesses are scattered (European Union 2018). Nonetheless, ePortfolios can increase the potential for matching successfully the skilled future employees with the companies that are recruiting.

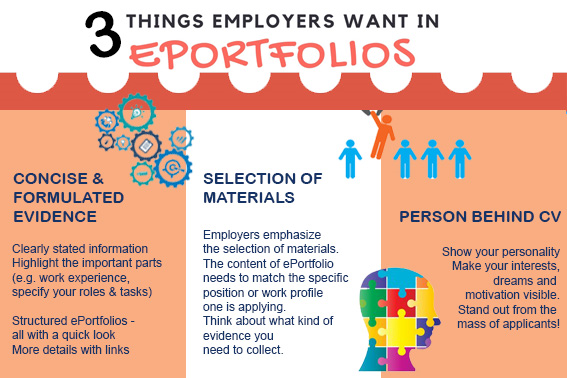

What is it then that the employers value in ePortfolios? The findings illustrated in Figure 1. are summarized in three main points: 1) concise and formulated personal evidence of competences, 2) selection of evidence or materials, and 3) person behind the CV.

The employers emphasized that ePortfolios need to be well structured and all the main information should be available in an understandable format with a quick look. They also highlighted that if they want to go deeper into something very specific, they should be able to find more details behind links. Thus, the structure and navigation should be carefully thought in order to make it simple and logical but having different layers of information. Another important issue the employers pointed out is that some crucial information e.g. work experience should be opened up in more detail to the reader. It means that instead of using just titles (place, position), one should explain more what the specific roles and tasks were, in what kind of networks one operated, etc.

This leads to the next point, which is selection. The employers accentuated that the content of ePortfolio should match the specific position or work profile, i.e. one should select from all the materials the ones that are relevant evidence of competences for a specific work position they are applying. In addition, it is beneficial to think about what kind of other material can support this specific application process – perhaps something from the leisure time activities e.g. voluntary work or maybe evidence of personal characteristics. In any case, the materials one selects should highlight the person behind the ePortfolio, which leads to the third point the employers pointed out.

Employers are mostly looking for the right kind of persons to fit to their working community, having the right kind of attitude and the way of working. Thus, it is important that they see the person behind the ePortfolio and all the selected evidence. Moreover, not only the person but also their dreams, visions, motivation, and what drives them further. As Dan Schawbel said in his blog on Forbes: “Job seeker passion has become the deciding factor in employment” (Forbes 2011)

Employers receive amounts of applications from equally educated and qualified people. This means that one needs to stand out from the mass and this can be done with cleverly planned and visually implemented ePortfolio where all the relevant information is available and also other supportive evidence to demonstrate e.g. transferable skills that are increasingly important for employability but in a much more flexible and visual way than mere CV.

Teachers’ engaging assessment and guidance processes

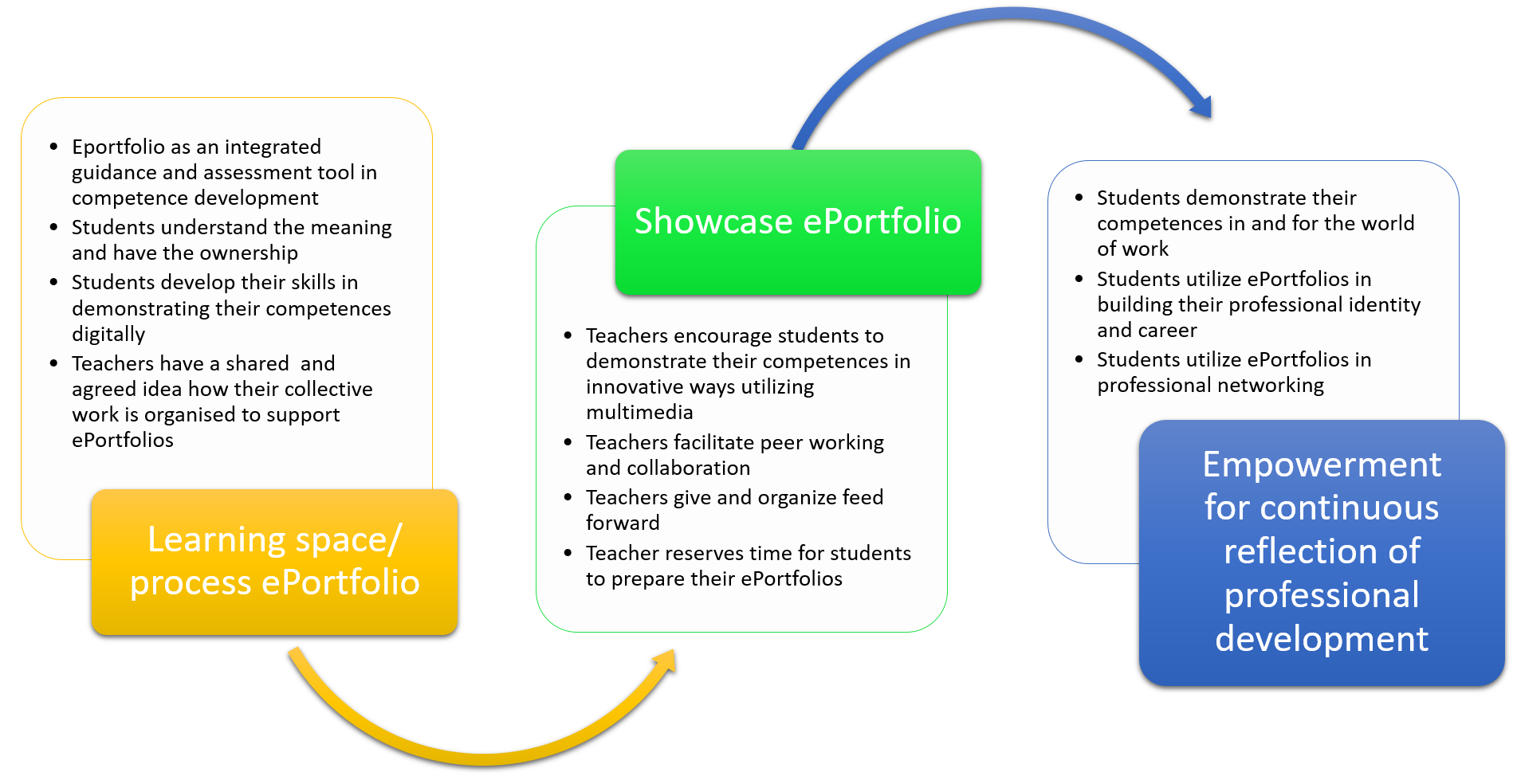

As has been stated before, the findings of the analysis on teachers’ processes reveal that ePortfolio as a learning space exists, although not systematically, but the second phase i.e. showcase ePortfolio is still rather challenging for many universities (see figure 2.). As the whole connection with the world of work, also the showcase ePortfolio process needs to be developed and requires new kind of thinking from the teachers and the educational organizations in how they understand their role in the surrounding society. In addition, students need to see the benefit of ePortfolios from the lifelong learning perspective, i.e. how they can utilize their ePortfolio after graduation as a tool to find their first employment and later on to build their professional identity and career aspirations.

The foundation for a successful use of ePortfolios as an essential part of learning processes is that it is embedded to curriculum. This means that ePortfolio process is in the structures and there is allocated time and resources to develop it. However, in order to establish the use of ePortfolio systematically in the entire programme (and organizational) level and throughout the studies requires that teachers collaborate with each other and plan the ePortfolio process together. Thus, at first teachers (or at least most of them) need to see the benefit of ePortfolios. Further, teachers need to realize how ePortfolios can support student-centered and competence-based education, continuous guidance and assessment processes and how students themselves should take the role in these processes and ownership of their own learning.

As in student-centered education in general, the role of a teacher shifts more towards a facilitator of learning and building of competences; this is the case with ePortfolios as well. Students need to have the ownership of their ePortfolios and freedom to build them the best way for their own purposes and goals. First, teachers need to justify the benefits and purpose of ePortfolios to students and then give them space for creativity in demonstrating the competences, collaborating with their peers and others as well as networking with the world of work. However, sometimes the structures of HEIs do not support the building of students’ ownership.

Many HEIs use standardized ePortfolio platforms that do not leave much space for students’ creativity. There are some good tailored examples of platforms (e.g. in IE with Mahara) that are structured but give some possibilities for students to modify the layout of their ePortfolios. Nonetheless, certain space for creativity motivates and engages students more and thus, builds up the ownership of their ePortfolios. Further, the ideal situation would be that students could choose their ePortfolio platform or tool themselves. Another issue, which could be solved with students’ own choice of ePortfolio is related to the ideology of lifelong learning; in many cases if the HEI has its own ePortfolio platform, the students lose their access to it after they graduate. They can only download the content but cannot edit it anymore. This is a problem when thinking about the whole purpose of ePortfolio as a tool to demonstrate personal and professional growth, especially in transition phases in life such as from education to employment. (e.g. Cejudo 2012; Vuojärvi 2013; Fiedler 2012)

In the creation of the showcase ePortfolio, the role of a teacher is crucial, as students do not always have a clear view of how to demonstrate their strengths – if they can first even identify them. In addition, sometimes students do not have a full understanding of the world of work and its requirements. Teachers need to encourage students to be innovative with feedforward and support the peer cooperation between students so that they can benefit from other points of view and further develop their own ideas and evidence of competences. (Kunnari, Laurikainen, Pires & Rodrigues 2017).

Conclusions and discussion

The results from the research on three perspectives (student, employer, teacher) on ePortfolios show that there already are good ePortfolio practices in Europe but mostly they are isolated islands within higher education institutions, not systematically implemented in programme (not to even mention institutional) level throughout the studies. The following conclusions and recommendations arise from the findings:

1) Understanding the benefits of ePortfolios:

- Teachers need to understand how ePortfolios can support students’ employability by making their skills and competences visible and transparent.

- Teachers need to highlight the lifelong learning perspective of ePortfolio and students need to understand how ePortfolio serves them in different situations in their lives. If they find the process meaningful and they are empowered and engaged during the ePortfolio process, this should happen automatically.

2) Embedding ePortfolios into curriculum and normal educational structures within the institution:

- Time and resource allocation for students to create ePortfolios and for teachers to facilitate and guide the process,

- Collaboration between teachers to implement the use of ePortfolios in the entire programme level

- Teachers need to understand assessment as a continuous process where students take an active role

3) Freedom and ownership of students:

- Teachers need to support the ownership of students in the ePortfolio process and give space for students’ creativity, collaboration with their peers and networking with world of work.

4) Skills needed

- Two types of digital skills are needed: technical skills to establish ePortfolio and editing skills to compile the content for ePortfolio

- In addition, certain transferable skills are needed and developed during the ePortfolio process (e.g. reflection, collaboration, communication, organization and visualization).

5) Clear formulation of the content of ePortfolio

- Concise and well-formulated personal evidence of competences

- Simple and clear structure (easily browsed, more detailed information available behind links)

- Selection of evidence to match the specific work profile the employer is looking for

- Selecting the evidence is probably the most difficult part in building up the ePortfolio. Perhaps one should have a “meta ePortfolio” with many kinds of information and select the most suitable evidence to a showcase ePortfolio that suits the specific situation or purpose.

6) Show personality

- Employers emphasized that they want to see the person behind the CV

- Show your interests, dreams, goals, passion and motivation in order to stand out from the mass of applicants

Even though this research was done in higher education context, these recommendations can be transferred to any level of education (with perhaps some adjustments in lower levels). The future generation, the digital natives are used to operating in digital environments from their first years of education and digital appearance is a norm to them. In addition, the digitalization of the world of work, and the whole society, requires new kind of digital management and presentation of competences and personal identity. It is easy to foresee that ePortfolio will be a common tool to be used in education (and beyond) in the future where the presence in digital networks and social media and digital branding is probably a skill one needs to learn very early on in life.

Authors

Marja Laurikainen, M.BA., Education Development Specialist (Global Education), Häme University of Applied Sciences

Irma Kunnari, M.Ed., PhD Fellow, Principal Lecturer (Global Education and Research), Häme University of Applied Sciences

[vc_tta_accordion active_section=”0″ no_fill=”true” el_class=”lahteet”][vc_tta_section title=”References” tab_id=”1458134585005-b3f22396-5506″]

Barrett, H. (2010). Balancing the Two Faces of ePortfolios, Educação, Formação & Tecnologias (Maio, 2010), 3 (1), pp. 6-14. Submitted: December, 2009 / Approved: March, 2010 http://eft.educom.pt/index.php/eft/article/viewFile/161/102

Biggs, J. & Tang, C. (2011). Teaching for quality learning at university. 4th Edition. The Society for research into higher education & open university press.

Cejudo, M. (2012). Assessing Personal Learning Environments (PLEs). An Expert Evaluation. New Approaches in Educational Research, 2(1), 39–44.

Choistealbha, J. (2018). The benefits and challenges of using ePortfolios. HAMK Unlimited Journal 31.1.2018. Retrieved 15 March 2018 from https://unlimited.hamk.fi/ammatillinen-osaaminen-ja-opetus/the-benefits-and-challenges-of-using-eportfolios

Connor, S. (2012) Using frames and making claims: the use of multimodal assessments and the student as producer agenda, Enhancing Learning in the Social Sciences, 4:3, 1-8.

Devaere, K., Martens E. & Van den Bergh, K. (2017). Analysis on students’ ePortfolio expectations. HAMK Unlimited Journal 5.1.2018. Retrieved 15 March 2018 from https://unlimited.hamk.fi/ammatillinen-osaaminen-ja-opetus/analysis-on-students-eportfolio-expectations

European Union (2017). DigComp Digital Competence Framework for citizens. Retrieved 10 March 2018 from https://ec.europa.eu/jrc/en/digcomp/digital-competence-framework

European Union (2018, June 8). The European Higher Education Area in 2018: Bologna Process Implementation Report. Retrieved 10 June 2018 from https://eacea.ec.europa.eu/national-policies/eurydice/sites/eurydice/files/bologna_internet_0.pdf

Fiedler, S. (2013). Emancipating and Developing Learning Activity: Systemic Intervention and Re-Instrumentation in Higher Education. Academic dissertation. University of Turku, Centre for Learning Research. Turku: Painosalama.

Forbes (2011). http://blogs.forbes.com/danschawbel/2011/02/21/5-reasons-why-your-online-presence-will-replace-your-resume-in-10-years, accessed on 15 March 2018.

Friedman, T. (2006). The World is Flat: a Brief History of the 21st Century. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Korhonen, A-M., Ruhalahti, S. & Torseke, J. (2017). How to put all my knowledge into words?. HAMK Unlimited Journal 13.12.2017. Retrieved 15 March 2018 from https://unlimited.hamk.fi/ammatillinen-osaaminen-ja-opetus/how-to-put-all-my-knowledge-into-words

Kunnari, I. & Laurikainen, M. (2017). Collection of Engaging practices on ePortfolio Process, pp. 7, Hämeenlinna, HAMK Publications. Retrieved 10 March 2018 from https://eepeu.wordpress.com/publications/

Kunnari, I., Laurikainen, M., Pires, A. O. & Rodrigues, M. R. (2017). Supporting students’ ePortfolio process in Higher Education. HAMK Unlimited Journal 12.12.2017. Retrieved [date] from https://unlimited.hamk.fi/ammatillinen-osaaminen-ja-opetus/supporting-students-eportfolio-process-in-higher-education

Kunnari, I., Laurikainen, M. & Torseke, J. (2017). Triggering students to create ePortfolios. HAMK Unlimited Journal 15.12.2017. Retrieved 15 March 2018 from https://unlimited.hamk.fi/ammatillinen-osaaminen-ja-opetus/triggering-students-to-create-eportfolios

Kunnari, I. & Lipponen, L. (2010). Building teacher-student relationship for wellbeing. Lifelong Learning in Europe. 2, 2010.

López-Fernández, O. (2009). Investigating university students’ adaptation to digital learner course portfolio. Computers & Education, 52(3), 608–616.

Medland, E. (2016). Assessment in higher education: drivers, barriers and directions for change in the UK. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 41(1), 81-96.

Pires, A., Rodrigues, M. & Pessoa, A. (2018). Transforming pedagogy in Higher Education. HAMK Unlimited Journal 26.1.2018. Retrieved 15 March 2018 from https://unlimited.hamk.fi/ammatillinen-osaaminen-ja-opetus/transforming-pedagogy-in-higher-education

Poulsen, B. K. & Dimsits, M. (2017). Making sense with ePortfolios. HAMK Unlimited Journal 20.12.2017. Retrieved 15 March 2018 from https://unlimited.hamk.fi/ammatillinen-osaaminen-ja-opetus/making-sense-with-eportfolios

Ryan, R.M. & Deci, E.L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55, pp. 68-78.

Van Eylen, K. & Deketelaere, A. (2018). Students’ perspectives on using an ePortfolio and their digital competences. HAMK Unlimited Journal 8.1.2018. Retrieved 15 March 2018 from https://unlimited.hamk.fi/ammatillinen-osaaminen-ja-opetus/students-perspectives-and-digital-competences

Vuojärvi, H. (2013). Conceptualising Personal and Mobile Learning Environments in Higher Education. Academic dissertation. University of Lapland. Rovaniemi: Lapland University Press.

Yin, R.K. (2009). Case Study Research. Design and Methods, (4th ed.). Applied Social Research Methods Series, vol. 5. USA: Sage Publications.

[/vc_tta_section][/vc_tta_accordion]