Sebastian King, Kaija Koivusalo & Ville Saarikoski

This article reports on an ongoing project between Laurea University of Applied Sciences and a consortium of universities to create a 3 ECTS online course called Working Across Borders (WAB). With over 600 students participating annually from around the world, the WAB project illustrates well the potential for international collaboration to transform higher education.

Digitalization and internationalization in education

The Covid-19 pandemic has drastically changed the digital education scene and brought digital solutions to the fore. However, the potential to disrupt education (Christensen, Johnson & Horn 2011) with digital technologies has existed for some time.

Digital transformation is a techno-economic systemic change (Henriette, Feki & Boughzala 2015; Zhu, Ge & Wang 2021) that is reshaping our society. In a systemic change all elements need to change in a strongly interrelated and coordinated way (Sweeney & Meadows 2010). They also need to break free from structures of the past. The future in a digital world is thus particularly fuzzy.

A digital product or service is often noted for its special characteristics. It is ubiquitous, has zero marginal cost (Shapiro & Varian 1999) and is highly scalable. From this setting MOOCs (Massive Open Online Courses) have emerged and these can be viewed as one solution that is presently in a strong state of diffusion. What else might be diffusing remains in the dark.

The pandemic highlighted the need for virtual mobility and internationalization-at-home (IaH). The COIL model of Collaborative Online International Learning (first introduced in 2000 by SUNY COIL) is seen as a cost-effective solution for promoting internationalization in Higher Education (Vahed 2022). COIL modules are co-taught by the staff of the participating institutions, all interaction is online, intercultural competences are developed, and the learning is integrated into the curricula of the participating universities (Rubin & Guth 2015).

Working Across Borders in a nutshell

The Working Across Borders project embodies the key elements of a COIL but on a larger scale, as in a MOOC. In its ongoing development, the initiative exemplifies how a collaborative learning module can be integrated into the curricula of very different universities and maintained for successive years. A key ingredient to its success is the promotion of student activity and engagement.

The WAB project is now running for its sixth year in fall 2022. During each implementation of the project more than 600 students from about 15 universities (in Europe, Asia, Africa, North and South America) work together on a company consultancy project for 2,5 months. Laurea UAS is at present the only university in Finland offering the project annually for bachelor and master students. The 3 ECTS project is embedded in the curricula of all partner universities.

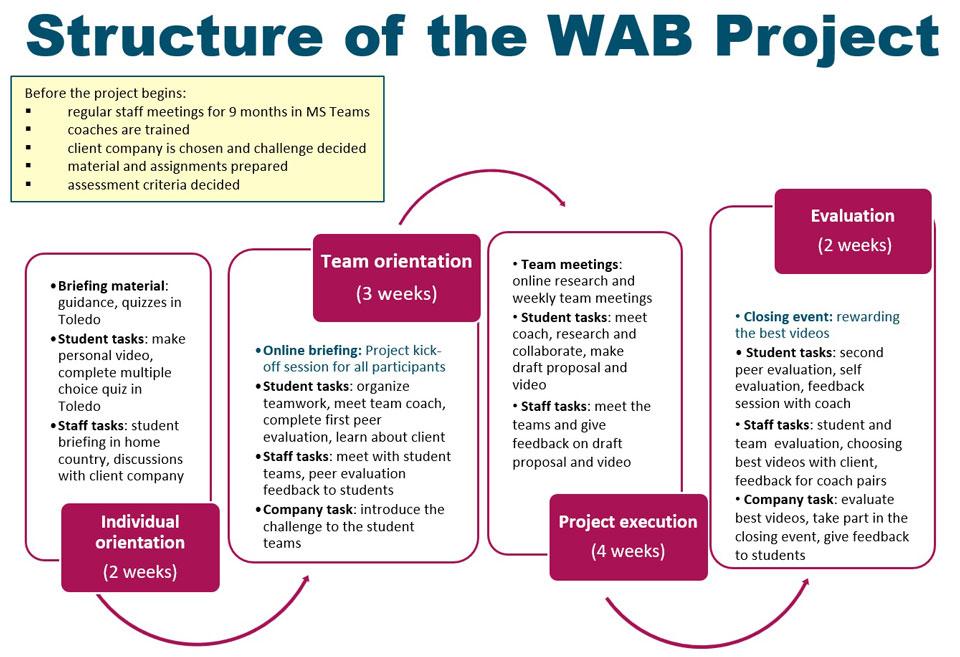

The impetus for the project came from the founder partner, University College Leuven-Limburg (UCLL) in Belgium, and today they supply the largest cohort of students. The basic structure of the project has remained the same through its iterations: after initial orientation, students are presented with a challenge by a client company in a kick-off ceremony; they are then divided into international teams to work on a solution to the challenge; finally, they present their solution at the end of the project, with the winning proposal selected by the client. During recent years clients have come from such sectors as urban mobility, clothing, flooring materials and cleaning products.

Benefits for students and clients

The project offers clear benefits to its stakeholders. Students exchange ideas and gain experience of the realities and challenges of cross-border collaboration. They develop intercultural competence while interacting with peers in multi-cultural teams, and skills in using collaboration tools common in today’s workplace.

In addition, students develop business competence by working on an authentic case for the client company. The precise nature of the challenge will depend on the client, but a common theme is sustainability. Cases focus on a target country, with several teams allocated one country and the whole group considering 10-15 target countries. In this way students also acquire practical understanding of cross-border business issues.

The benefits for the client are also evident. Although such project assignments are common in business programs, the scale of the WAB project is exceptional. Since there are typically over 600 students participating in the project, working in teams of 5, clients receive over 100 video presentations with innovative solutions for their particular challenge in a range of key markets. As well as being a rich source of ideas, the project offers an excellent opportunity to raise the company’s profile among a key demographic.

Development of the WAB concept

Throughout its development innovations have been introduced to help the WAB project better achieve its desired objectives.

A key issue in early iterations was uneven student activity and engagement. Students were placed on the project by their home institutions, but motivation levels were not equally high. This led to frustration in the teams as members struggled to contact teammates when completing project tasks. The effort participants were willing to put into achieving project outcomes was variable and some teams became dysfunctional.

Several solutions were developed to deal with this issue. In the first instance, it was felt that motivation levels were affected by the status of the project within the partner universities’ curricula. Early on it was agreed that the project become a part of the compulsory studies in the programs where it was implemented, ideally representing an equivalent workload of 3 ECTS. This would foster a common level of commitment as students viewed their activity as a key part of their studies and the stakes for working on the project would be even.

A further solution came by developing the project timeline as shown in Figure 1. Rather than placing all students in teams from the outset and having them immediately work on the business case, two preliminary phases were created to allow individual and then team orientation. A tollgate at the end of the individual phase was set so inactive students would naturally drop out and not be placed on a team. Materials and tasks created for these phases were designed to be engaging and raise awareness of issues likely to be encountered.

A third innovation was to develop the tools for collaboration and interaction offered to students. In early iterations students had been left to discover their own methods. This inevitably led to over-reliance on WhatsApp and poor systems of document collaboration. MS Teams was thus introduced for all teams and online meetings encouraged already in the team orientation phase.

Also important was the development of a role for coaches within each participating institution to guide teams forward. A final innovation related to the development of peer assessment checkpoints to ensure students focus on behaviours to facilitate collaboration and sensitivity to teamwork issues.

In some respects, the staff developing the project have faced challenges similar to those of the student teams.

In particular, the importance of regular face-to-face meetings online was soon recognized. These are held from January onwards on a weekly or fortnightly basis with members joining in from Ecuador to Indonesia. The meetings are used to discuss such matters as reviewing the feedback from the previous implementation, selecting the client, defining the tasks that need to be carried out, rewriting guidance materials, and preparing instructions and assessment rubrics. During the implementation phase, meetings focus on practical matters needing urgent attention.

A key to effective collaboration has been acceptance of the need to divide the workload fairly, so that for example meetings have a rotating chairperson and working groups are set up to carry out tasks. Cultural differences can perhaps be observed in terms of variations in assessment practices, or differing attitudes to deadlines, but meetings are always good natured, and the spirit of collaboration is very strong. Over the years the exact composition of the project partners has changed and the question of how to smoothly integrate new arrivals into project preparation and delivery perhaps remains to be resolved.

Reflections and future directions

The WAB project continues to evolve with each iteration. In future more can be done to maximize the networking potential of the project for its participants, and gamification elements could be introduced to further stimulate engagement.

From the student perspective, WAB resembles a MOOC in terms of its size and global reach. This is brought home during the kick-off and closing sessions when everyone is present online. One challenge of MOOCs is the high drop-out rate (Burd, Smith & Reisman 2015) and in its early iterations this was an issue with WAB, specifically a lack of engagement and participation. To tackle this issue attention had to be paid to how the project was structured.

Unlike MOOCs, which are open, WAB has restricted access. In MOOCs students participate as individuals, whereas WAB is a collaborative enterprise for participants and creators. The WAB project seems, in hindsight, to have combined elements of COIL implementations and MOOCs. In a sense, it could be described as a MOCC, or Massive Online Collaborative Course.

The WAB project has provided an opportunity to move outside a national educational system context and its potentially interlocked established practices to rediscover the relationships between the parts and reorganize these to work together in a novel way.

Ultimately, the WAB project provides a great window of exploration to study the potential for digital transformation and systemic change in the education sector. Dufva & Dufva (2019) refer to digital grasping, while Johnson (2011) sees spaces of innovation, i.e., where good ideas emerge, as coffee houses, underlining that good ideas need time to incubate with the collision of slow hunches and “the adjacent possible”. The WAB project has created for several years, using Johnson’s terminology, “a coffee house” for discovery.

Sebastian King, Senior Lecturer, MA, Laurea University of Applied Sciences, sebastian.king(at)laurea.fi

Kaija Koivusalo, Senior Lecturer, MSc, Laurea University of Applied Sciences, kaija.koivusalo(at)laurea.fi

Ville Saarikoski, Principal Lecturer, PhD, Laurea University of Applied Sciences, ville.saarikoski(at)laurea.fi

References

Burd, E. L., Smith, S. P. & Reisman, S. (2015). Exploring business models for MOOCs in higher education. Innovative Higher Education. Vol. 40, no. 1, pp. 37–49. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10755-014-9297-0

Christensen C. M., Johnson C. W. & Horn M. B. (2011). Disrupting class : how disruptive innovation will change the way the world learns. New York: McGraw-Hill Professional.

Dufva, T. & Dufva, M. (2019). Grasping the future of the digital society. Futures. Vol. 107, pp.17-28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2018.11.001

Henriette, E., Feki, M. & Boughzala, I. (2015). The shape of digital transformation: a systematic literature review. MCIS 2015 Proceedings. 10. Accessed 26 October 2022. https://aisel.aisnet.org/mcis2015/10/

Johnson, S. (2011). Where good ideas come from: the seven patterns of innovation. London: Penguin.

Rubin, J. & Guth, S. (2015). Collaborative online international learning: an emerging format for internationalizing curricula. In: Moore, A. S. & Sunka, S. (eds). Globally networked teaching in humanities. New York: Routledge.

Shapiro, C. & Varian, H. R. (1999). Information Rules – A Strategic Guide to the Network Economy. Boston, Mass.: Harvard Business School Press.

Sweeney, L. B. & Meadows, D. L. (2010). The systems thinking playbook : exercises to stretch and build learning and systems thinking capabilities. White River Junction Vermont: Chelsea Green.

Vahed, A. (2022). Factors enabling and constraining students’ collaborative online international learning experiences. Vol. 25, no. 3, pp. 895-915. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10984-021-09390-x

Zhu, X., Ge, S. & Wang, N. (2021). Digital transformation a systemic literature review. Computers and Industrial Engineering. Vol. 162, C. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cie.2021.107774