Introduction

Entrepreneurship education has been high on the European agenda for many years as an effective mean of embedding an entrepreneurial culture in higher education institutions (HEI). Higher education has not traditionally prepared students for self-employment as HEIs’ primary mission has been to prepare students for employment (Fenton & Barry, 2014). Higher education is facing challenges in the definition of its purpose, role, and scope in society and the economy, and therefore universities have been recommended to expand their entrepreneurship education (OECD, 2012). Entrepreneurship education has evolved considerably in recent decades and it has gained both academic and political credibility (Henry, 2013).

Entrepreneurship education in higher education has shown to have a positive impact on the entrepreneurial mindset of students, their intention towards entrepreneurship, their employability and finally on their role in the society and the economy (European Commission 2012). At the global level entrepreneurship education is portrayed as critical to employment generation, innovation and economic growth and, therefore, it is promoted as a necessary core rather than an optional peripheral aspect of higher education curricula (Henry, 2013). The expectations for entrepreneurship education are high and e.g. Henry (2013) suggests that policy makers’ expectations may even have spiralled beyond what is both realistic and possible.

The entrepreneurial intentions of students at Finnish Universities of Applied Sciences (UAS) and in secondary education have been studied in a longitudinal research (Joensuu et al. 2014). In that study it was found that the entrepreneurial intentions of UAS students decrease during their studies. One reason for this seems to be that at the beginning of the studies students have more positive attitudes towards entrepreneurship as the time to actually make the decision to start a business after graduation seems to be far in the future. As they near graduation, their opinions towards entrepreneurship become more realistic and cautious. Furthermore, it was found that taking general entrepreneurship studies does not have an effect on entrepreneurial intention. However, entrepreneurial pedagogy requiring active participation of the students has a positive effect on the students’ confidence in their entrepreneurial capabilities and this in turn has a positive effect on entrepreneurial intentions (Joensuu et al. 2014).

A relevant policy-oriented question whether it would make more sense for a certain group of students to take more comprehensive entrepreneurship education rather than all students taking only basic entrepreneurship education has been raised (Søren, 2014). Entrepreneurship-specific education may provide students with an opportunity to accumulate transferable skills that can be employed in any organizational context, not only in business start-ups (Solesvik, Westhead, Matlay & Parsyak, 2013). This view supports the idea of offering entrepreneurship education widely in HEIs. On the other hand, if we think that entrepreneurship education should enhance students’ business start-ups, we should give more specific coaching for those students who already have entrepreneurial intention. As Fenton and Barry (2014) state, it is a fallacy to assume that more entrepreneurship education provision will lead to immediate graduate entrepreneurship as the route to self-employment is influenced by personal circumstances.

Another critical question raised within entrepreneurship education research is what we are really doing when we provide teaching and training in entrepreneurship. According to Fayolle (2015), we should think more critically about the appropriateness, relevance, coherence, social usefulness and efficiency of practices in entrepreneurship education. Entrepreneurship education is at the crossroads of entrepreneurship and education and, therefore, it should have a solid theoretical and conceptual foundation drawing from these both fields.

Keeping these two relevant and critical questions in mind, in this paper’s theoretical background the theoretical foundation behind our decision to concentrate on students with entrepreneurial intention is described firstly. Secondly, the educational foundation for our entrepreneurial coaching model is discussed.

Terms Related to Entrepreneurial Coaching

In research and political reports terms entrepreneurship education, enterprise education and entrepreneurial education seem to be used as related terms. However, these terms are slightly different and e.g. UK’s Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education QAA (2012) has defined enterprise education as follows: ’Enterprise education aims to produce graduates with the mindset and skills to come up with original ideas in response to identified needs and shortfalls, and the ability to act on them. In short, having an idea and making it happen’. Whereas entrepreneurship education ‘focuses on the development and application of an enterprising mindset and skills in the specific contexts of setting up a new venture, developing and growing an existing business, or designing an entrepreneurial organisation.’ (QAA, 2012, 8). The ultimate goal of enterprise and entrepreneurship education is to develop entrepreneurial effectiveness which can be defined as ‘the ability to behave in enterprising and entrepreneurial ways. This is achieved through the development of enhanced awareness, mindset and capabilities to enable learners to perform effectively in taking up opportunities and achieving desired results’ (QAA, 2012, 10-11).

This study describes one model of entrepreneurship education called entrepreneurial coaching which is offered to master level students at Savonia University of Applied Sciences. In this study the term entrepreneurship education is used when discussing entrepreneurial, enterprise and entrepreneurship education in general, and when discussing the entrepreneurship education model of our university the term entrepreneurial coaching is used. Coaching as a term describes well our model which has a personalized approach focusing not only on the business idea but on the student as an individual. This model creates a context of learning that equips the students to find answers themselves through a creative process. The coach plays the role of a facilitator or catalyst but does not provide ready-made answers (see e.g. Audet & Couteret, 2012; International Coaching Federation, 2016).

Objectives, Approach and Methods

This study describes the foundations, model and methods of entrepreneurial coaching which is offered to the master level students of Savonia University of Applied Sciences. The students’ expectations for the coaching and how they utilize it to develop their business ideas are examined. An earlier version of this paper was presented in the RENT-conference in Zagreb, Croatia in November 2015 (Laukkanen & Iire, 2015).

In this study the students and their views are placed into focus, and it is examined how entrepreneurial coaching may enhance their personal development as entrepreneurs. Our entrepreneurial coaching model is presented as one way to enhance master level students’ capabilities and courage to start and develop their own businesses. The aim of the paper is to strengthen the entrepreneurship education research by analysing openly the educational foundations of our entrepreneurial coaching model. As Jones et al. (2014) state, in order to promote the development of entrepreneurship education it is important that the educators ‘reflect upon their practice, identify their teaching orientation and question their emphasis upon certain contents, processes and outcomes’ (Jones et al. 2014, 773).

This study adopted a qualitative research approach and a theme-based survey was conducted among 17 students who participated in entrepreneurial coaching. This data was used to describe the expectations of the students and the ways they utilize the coaching to develop their business ideas. We also arranged a kick-off seminar for these students and there we discussed their expectations and challenges concerning entrepreneurship. These discussions gave more depth to the themes which rose from the survey.

Furthermore, a more detailed look was taken into the coaching processes of four students with very different starting points, and short case stories of these students are told. Two of the students develop together a business idea which is based on their new product and service innovation. The third student is already an entrepreneur, but his business lacks all formal business planning, business model and formal strategy. The fourth student has a business idea based on her knowledge and skills which have developed during her long working experience. By these case stories it is depicted how this kind of flexible entrepreneurial coaching model can benefit students in their personal circumstances. These particular students were chosen as they have so different starting points.

Entrepreneurial Coaching Model – to Whom, What, How and Why?

In this chapter two critical perspectives related to whom and how entrepreneurship education should be implemented are discussed. Firstly, the theoretical foundation behind our decision to concentrate on master students with entrepreneurial intention is described. Secondly, the educational foundation of our entrepreneurial coaching model is discussed.

Entrepreneurship Education and Coaching for All or Only for Those with Entrepreneurial Intention

In entrepreneurship education research there is a lot of discussion around the question whether it would make more sense in higher education institutes to offer some students more comprehensive entrepreneurship education rather than some entrepreneurship education for a large group of students or even all students. The view which supports offering entrepreneurship education widely in HEIs states that entrepreneurship-specific education may provide students with an opportunity to accumulate transferable skills that can be employed in any organizational context, not only in business start-ups (Solesvik et al., 2013). Entrepreneurship-specific education has stated to accumulate the human capital assets required for entrepreneurial careers in new, established, small, large, public and private organizations (Solesvik, Westhead & Matlay, 2014).

Entrepreneurship education is booming worldwide, and entrepreneurship is becoming increasingly popular in business schools, engineering schools, universities and educational institutions (Fayolle, 2015). European Commission has adopted a very wide description of EE in a recent report saying that entrepreneurship education is taken to cover all educational activities that seek to prepare people to be responsible, enterprising individuals who have the skills, knowledge and attitudes needed to prepare themselves to achieve the goals they set for themselves to live a fulfilled life (European Commission, 2015). Offering entrepreneurship education widely in educational institutions has an important role producing skills to future entrepreneurs so that they are capable of thinking, acting and making decisions in a wide range of situations and contexts (Fayolle, 2015).

On the other hand, if we think that entrepreneurship education should enhance students’ business start-ups, it demands more specific education and coaching for those students who already have entrepreneurial intentions. Donellon et al. (2014) argue that while demand for entrepreneurial competence has led to constant growth of entrepreneurship education, few programmes provide robust outcomes such as actual new ventures or entrepreneurial behaviour in real contexts. They emphasize that beyond acquiring knowledge and skills, entrepreneurial learning also involves the development of an entrepreneurial identity (Donellon, Ollila & Williams Middleton, 2014). Furthermore, the route to self-employment is highly influenced by personal circumstances (Fenton & Barry, 2014).

There seems to be a gap between entrepreneurial intention and action (Van Gelderen, Kautonen & Fink, 2015; Gielnik et al., 2014). Many people form intentions to start their own businesses but do little to translate those intentions into action. Acting upon intentions may be postponed or abandoned for several reasons; new constraints emerge, a person’s preferences change, or feelings of fear, doubt or aversion rise. Van Gelderen et al. (2015) show that self-control positively moderates the relationship between intention and action. It seems that supporting only the development of entrepreneurial knowledge does not necessarily lead to action, whereas factors of entrepreneurial goal intentions, positive fantasies, and action planning have combined effects on new venture creation (Gielnik et al. 2014).

At our university entrepreneurship is considered an important thing to promote since we see it as one way to develop the economy and well-being of the region. Therefore, at our business school we offer all students general entrepreneurial skills which are useful in all organizational contexts and may lead to business start-ups in future. All bachelor level business students get general knowledge and skills of entrepreneurship since these issues are taught in academic courses. They all also practice entrepreneurship skills during their first year in a virtual enterprise which they establish in teams of ten students. After this, all business students also at the bachelor’s level have an opportunity to choose entrepreneurial coaching courses if they have a preliminary business idea and/or entrepreneurial intentions.

The master’s level entrepreneurial studies are aimed at those students who already have entrepreneurial intentions. They choose these studies knowing that the goal is to develop their own business ideas and business models. We have named these studies entrepreneurial coaching to separate them from more general entrepreneurship education. In addition, we think that the term ‘coaching’ describes our model very well as coaching discussions are an essential part of the process. These entrepreneurial coaching studies are offered also to students from other fields than only business. At the master’s level we have had students from the business, tourism, engineering and healthcare sectors. Several previous studies have also emphasized that entrepreneurship education should move beyond the traditional business school context and offer entrepreneurial learning pathways also to students from other faculties or schools (Jones, Matlay and Maritz, 2012; Crayford et al. 2012).

Educational Foundation for Entrepreneurial Coaching

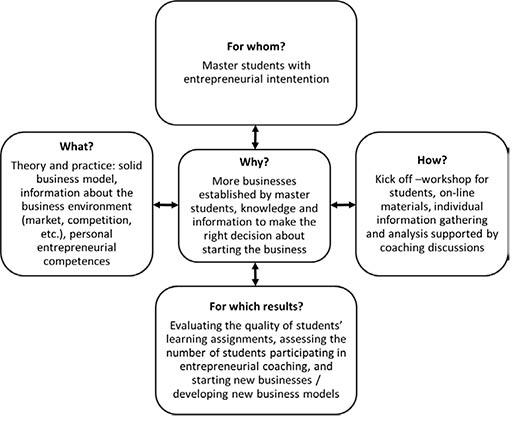

Fayolle (2015) emphasizes that entrepreneurship education should have a strong intellectual and conceptual founding drawing from the fields of entrepreneurship and education. Similarly Jones et al. (2014) call for stronger pedagogical content knowledge for entrepreneurship education. In his article Fayolle (2013) presents a good generic teaching model for entrepreneurship education. In this paper his model is used as a basis to give a comprehensive description of the educational founding for our entrepreneurial coaching (figure 1).

The entrepreneurial coaching studies for master’s level students at our university consist of three courses (5 ECTS each). Students can include these studies in their curricula as elective studies, and they can choose one, two or three of these courses. In the following the studies are described in more detail.

For whom?

The students are studying at Savonia University of Applied Sciences in order to get a master’s level degree. They already have a bachelor’s level degree and at least three years of working experience after completing the bachelor’s degree. They have preliminary business ideas, and/or entrepreneurial intentions. The students’ reasons for participating in these studies vary. Some of them already have quite clear business ideas which they want to develop into solid business models. Some students have the entrepreneurial intentions, but not any clear business ideas. Some of them are already entrepreneurs, but they feel that their business ideas and models need to be clarified.

Why?

One clear objective for offering these studies is to increase the number of master’s level students’ business start-ups. However, achieving this goal takes time and the actual starting up may happen years after completing the degree. Another important goal is to give master students an opportunity to take time to ponder their entrepreneurial and personal goals and find versatile information about the industry, markets, competition, etc. which helps them to make decisions.

We also tell our students that these studies give them an opportunity to gather information to make the right decision whether to proceed with the business idea towards a start-up, or to postpone or abandon the commercial use of the idea. This is an ethical issue; we should also help the students to make a no-go decision if, after wide and versatile information gathering and analysis, it seems that the business idea has no commercial potential.

What?

In our entrepreneurial coaching model we mix theoretical knowledge and practice-oriented approaches. The theoretical knowledge contains issues such as opportunity recognition, business model generation, business environment analysis and entrepreneurial skills. These issues are discussed in a kick-off workshop and in on-line materials. The students are expected to find more information about these issues focusing on their own business ideas. Otherwise the studies are very practice-oriented as the students work on their own ideas. The students’ information gathering and individual pondering is supported by coaching discussions when needed.

The coaching teachers also have skills that mix theoretical and practical knowledge. There are two ‘main coaches’, one of them has a doctoral degree in entrepreneurship and has been an entrepreneur herself, the other has a master’s degree in administrative sciences and a long and profound experience in developing business models in organizations. In addition, other professionals at our university can be employed as coaches when their special knowledge is needed (for example innovation management or financial management issues).

How?

The entrepreneurial coaching process starts with a kick-off workshop for the whole group. In this workshop the students are offered short lectures on essential entrepreneurship knowledge. After that the students brainstorm and jointly develop the ideas. They also study how to use business model generation tools.

After that the students start to work on their own business ideas independently and the development process is supported during coaching sessions with the teachers. The coaching teachers also provide ideas on how the students should and could develop the needed network. An on-line learning environment is formed to contribute to the learning process. In the learning environment the students find relevant material, links and they can also ask the coaches questions. The students report on their learning by producing written learning assignments.

The studies consist of three separate courses, and a student can choose only one or two, or all three of them. These three courses have different learning objectives. In the first course the students ponder their own entrepreneurial intentions and skills and form the first business model around their business ideas. In this phase the students critically analyse their own entrepreneurial motivation and skills. The students are advised to enhance their self-reflection with tests which measure entrepreneurial intentions and capabilities.

In the second course they choose and justify one specific part of their business model which needs further studying and gather information related to this. And finally in the third course the students should be able to present holistic and profound business models and plans to show how they are going to turn their ideas into business. At this stage the students should form action plans on how their entrepreneurial intentions will translate into action (see e.g. Van Gelderen et al. 2015). At all stages the students are expected to gather versatile theoretical and practical information.

For which results?

The students develop their business ideas and models and they report on the development processes in the learning assignments. These assignments are evaluated and the students get their grades on the basis of the evaluation criteria which include e.g. the following: setting and achieving the goals of the process, use of versatile and profound knowledge base (theoretical and practical), usefulness of the gained information, versatile and professional discussion and reporting and logical conclusions. The students also get feedback which helps them to move forward in the development of their business models.

We assess the entrepreneurship outcomes of the coaching by following the number of students who participate, the start-ups of the students and new business models developed for the existing firms of the students. However, it is difficult to report on these assessments yet since the processes of the students are long and the actual results often come about later.

Students’ Experiences of Entrepreneurial Coaching

As mentioned, master students’ reasons for participating in entrepreneurial studies vary. In a survey among the students their motives to participate were asked, and we also discussed these motives during a kick-off workshop and coaching discussions. Some of the students have strong entrepreneurial intentions and quite clear business ideas, while some have the intention, but the business idea is still very vague. There are also students who have clear business ideas, but they want to take time to ponder how they could match entrepreneurship with their personal circumstances. And finally, there are students who already are entrepreneurs, but whose business ideas and models need to be clarified. Therefore a flexible coaching model is good for master students as it takes into account the students’ personal circumstances. Here are some citations to describe these different motives:

My goal is to explore profoundly if my business idea has real potential and if I have it in me to be a successful entrepreneur.

I want to attain more knowledge about entrepreneurship. On the other hand, these studies ‘force’ me to reflect my entrepreneurial skills and explore the potential of my business idea.

I want to clarify our firm’s business model. We haven’t done what we should have done at the beginning stage of the firm… Now it is a good time to clarify these essential aspects of our business.

We have students from different sectors; business, tourism, engineering and health care. This gives us a challenge as the students have different educational backgrounds. Business and tourism students already have quite strong general business and entrepreneurship knowledge, whereas engineers and students with health care degrees have studied these subjects much less. Therefore, some of the students expected to have more lectures on general business themes such as forms of enterprise and financial issues.

The execution of the studies is good. However, I expected to get more general business information – I mean basic things about issues which entrepreneurs face when they start a business. Having an opportunity for coaching discussions is great.

The participating students have found it important to get the opportunity and support to develop their business ideas as part of their studies. This seems to be one good way to promote the business start-ups of graduates as well as to enhance the chances of success of their businesses. As Fenton and Barry (2014) also found, entrepreneurial coaching at the graduate level provides a welcome ‘breathing space’ to develop students’ business ideas.

I find entrepreneurial coaching very useful for me. It is great that I have this opportunity to explore the potential of my idea as a part of my studies.

It is extremely important to get support for developing my business idea and get more knowledge from entrepreneurship experts.

The best way to describe the versatile motives, situations and processes of the students might be to tell short case stories. Therefore the stories of four students are told here: Helen and Sarah (innovation based idea), John (existing firm with no formal business model), and Mary (knowledge based idea). The names of the students are changed to ensure their anonymity. The processes of these students are still going on, and therefore the final outcomes and decisions which they will make concerning their business ideas cannot yet be told. These stories describe their entrepreneurial processes so far.

Helen and Sarah are master students from two different fields; Sarah is a business student and Helen is a healthcare management student. They met in an innovation knowledge course where they worked in the same study team and developed Helen’s original innovation idea which is a mobile phone application for persons with a certain type of food allergy. During the first course of entrepreneurial coaching they defined the customer segments for their application, analysed competition and formed their first business model draft. Helen and Sarah concluded in their report that they now have a preliminary understanding of the earning logic of their business. However, they now need a more profound market survey, and they need to plan and design the application. They are planning to focus on these aspects in their second and third entrepreneurial coaching courses and utilize the know-how of our university’s other departments (technology and design management).

John’s friends established a new firm in 2012 after recognizing a new import business opportunity. John started working for the company in autumn 2012 and bought his share of stocks in spring 2013. All three key persons had a technical education and background. Due to the strong demand, the business was good and the customers were found quite easily. The whole company adopted a culture of busy doing; there was no role for planning and foreseeing. John began to think about the future in the longer run. He started his master level business studies and soon realised that there is a huge need in their company to both increase efficiency and plan a proper business strategy for long term success. John took the entrepreneurial coaching studies because of the proper opportunity to take time to think about his own skills as an entrepreneur and also plan his business further. He is preparing the business model for their company. He thinks that the support from the tutoring professionals (coaching teachers) and the opportunity to think and plan by himself and reflect the results with the fellow students and tutors are the main reasons to participate in the entrepreneurial coaching studies.

Mary has a profound professional background as a controller, and she had an idea of starting her own business which would offer controlling and financial management services to entrepreneurs who lack these skills (firms which have been established leaning on the entrepreneurs’ professions). She developed the business model through versatile information gathering from both theory and practice. The practical information was gathered from managers in different sectors, and she also offered these services to one small company in the health care sector and tested the service there as a pilot case. During this process Mary found that there would be actual demand for her service business. However, she started to feel that this business would be too similar to the work she had done as an employee for a long time. Her interest started to focus more on the health care sector during her pilot process, and she now looks for new business opportunities in that sector. She also wants to be a part of a team instead of working as a consultant for a one- woman firm.

By telling these three case stories it is shown how different the starting points of students can be. Therefore we cannot offer some kind of one-size-fits-all solutions in entrepreneurial coaching. Instead, we need to appreciate the personal goals of the participants.

Conclusions and Implications

This study provides guiding principles for good practices in entrepreneurial coaching in higher education, and especially in practice-oriented universities such as universities of applied sciences. The findings of this study show that there is a need for a flexible entrepreneurial coaching model for master level students. On the basis of our experiences it can be said that entrepreneurial coaching should be student focused taking personal circumstances into account. Furthermore, the entrepreneurial studies should be compatible with the students’ curricula. This means that the curriculum is flexible enough and these entrepreneurial coaching studies can be included into the students’ personal study plans.

Using versatile learning methods seems to be good for developing entrepreneurial skills. A kick-off workshop where students become familiar with the business model development combined with e-learning environment and on-line material gives basis for the work which the students do independently. The students’ independent learning is supported in coaching discussions.

During this process the students also reflect and develop their own entrepreneurial identity. As Donellon et al. (2014) argue; if the educational objective is learning for the practice of entrepreneurship, then entrepreneurial identity construction is as important a goal as the development of knowledge and skills. The students are encouraged to critically evaluate their own skills and life goals and reflect them to attributes related to successful entrepreneurship. Context is an important contributor to entrepreneurial identity and the students need to confront their own internal dialogue about how the entrepreneurial identity fits with their social groups’ expectations and their own life expectations. We encourage our students to do this kind of reflection as part of their learning assignments.

Through the entrepreneurial coaching process master level students enforce their capabilities to develop their business ideas and business models. The process also enhances their courage to take their first steps (or new direction) as entrepreneurs. The students of our entrepreneurial coaching seem to have gained similar kind of immediate value as Kirkwood et al. (2014) also reported: confidence, entrepreneurship knowledge and skills, a sense of reality and practical solutions (Kirkwood, Dwyer and Gray, 2014). The coaching process forces the students to gather versatile information related to the planned business model. Therefore they will form stronger confidence in their skills. This and the coaching discussions enhance the courage to take the needed steps.

The entrepreneurial coaching process is an important learning experience also for those students who, after profound information gathering, decide to postpone or abandon the commercial use of their ideas. The process has offered them experimental learning opportunity which may in future give them better skills to recognize and analyse potential business opportunities, and gather versatile information to form solid business models.

This study contributes to entrepreneurship education research by presenting one model how entrepreneurial coaching can be organized in higher education. As Fayolle (2015) states, it is important that entrepreneurship education has a solid theoretical and conceptual foundation, drawing from both entrepreneurship and education. Therefore our model’s educational foundations are also clearly opened in this paper.

There are certain limits to this research, as it was undertaken at one university of applied sciences, and in a unique, regional environment. Therefore, it is influenced by policies, priorities and factors of the region and our university. However, by describing our model openly we hope to encourage entrepreneurship education professionals to develop practice-oriented coaching models using blended teaching methods.

Author

Virpi Laukkanen, Savonia University of Applied Sciences, Principal Lecturer, Ph.D. (Econ.), Virpi.Laukkanen(at)savonia.fi

[vc_tta_accordion active_section=”0″ no_fill=”true” el_class=”lahteet”][vc_tta_section title=”References” tab_id=”1458134585005-b3f22396-5506″]

Audet, Josée and Couteret, Paul. 2012. Coaching the entrepreneur: features and success factors. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 19 (3), 515-531.

Crayford, Judith, Fearon, Colm, McLaughlin, Heather and van Vuuren, Wim. 2012. Affirming entrepreneurial education: learning, employability and personal development. Industrial and Commercial Training, 44 (4), 187-193.

Donnellon, Anne, Ollila, Susanne, Williams Middleton, Karen. 2014. Constructing entrepreneurial identity in entrepreneurship education. The International Journal of Management Education, 12 (2014), 490-499.

European Commission. 2012. Effects and impact of entrepreneurship programmes in higher education. European Commission, DG Enterprise and Industry.

European Commission. 2015. Entrepreneurship Education: A road to success – A compilation of evidence on the impact of entrepreneurship education strategies and measures. European Commission, Directorate-General for Internal Market, Industry, Entrepreneurship and SMEs.

Fayolle, Alain. 2015. Personal views on the future of entrepreneurship education. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 25 (7-8), 692-701.

Fenton, Mary & Barry, Almar. 2014. Breathing space – graduate entrepreneurs’ perspectives of entrepreneurship education in higher education. Education + Training, 56 (8/9), 733-744.

Gielnik, Michael, M., Barabas, Stefanie, Frese, Michael, Namatovu-Dawa, Rebecca, Scholz, Florian, A., Metzger, Juliane, R. & Walter, Thomas. 2014. A temporal analysis of how entrepreneurial goal intentions, positive fantasies, and action planning affect starting a new venture and when the effects wear off. Journal of Business Venturing, 29 (6), 755-772.

Henry, Colette. 2013. Entrepreneurship education in HE: are policy makers expecting too much? Education + Training, 55 (8/9), 836-848.

Higgins, David & Elliot, Chris. 2011. Learning to make sense: what works in entrepreneurial education? Journal of European Industrial Training, 35 (4), 345–367.

International Coaching Federation. 2016. What is professional coaching? http://coachfederation.org/need/landing.cfm?ItemNumber=978&navItemNumber=567. Last accessed 6th October 2016.

Joensuu, Sanna, Varamäki, Elina, Viljamaa, Anmari, Heikkilä, Tarja and Katajavirta, Marja. 2014. Yrittäjyysaikomukset, yrittäjyysaikomusten muutos ja näihin vaikuttavat tekijät koulutuksen aikana. Seinäjoen ammattikorkeakoulun julkaisusarja A. Tutkimuksia 16.

Jones, Colin, Matlay, Harry and Maritz, Alex. 2012. Enterprise education: for all, or just some? Education + Training, 54 (8/9), 813-824.

Jones, Colin, Matlay, Harry, Penaluna, Kathryn & Penaluna, Andy. 2014. Claiming the future of enterprise education. Education + Training, 56 (8/9), 764-775.

Kirkwood, Jodyanne, Dwyer, Kirsty and Gray, Brendan. 2014. Students’ reflections on the value of an entrepreneurship education. The International Journal of Management Education, 12 (2012), 307-316.

Laukkanen, Virpi & Iire, Antti. 2015. Entrepreneurial Coaching for Master Students. Supporting Skills and Courage. Proceedings of RENT XXIX –conference. Research in Entrepreneurship and Small Business, Zagreb, Croatia, November 18-20, 2015.

OECD. 2012. A Guiding Framework for Entrepreneurial Universities.

QAA. 2012. Enterprise and entrepreneurship education: Guidance for UK higher education providers. The Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education.

Solesvik, Marina, Westhead, Paul, Matlay, Harry & Parsyak, Vladimir, N. 2013. Entrepreneurial assets and mindsets. Benefit from university entrepreneurship education investment. Education + Training, 55 (8/9), 748-762.

Solesvik, Marina, Westhead, Paul & Matlay, Harry. 2014. Cultural factors and entrepreneurial intention. The role of entrepreneurship education. Education + Training, 56 (8/9), 680-696.

Støren, Liv Anne. 2014. Entrepreneurship in higher education. Impacts on graduates’ entrepreneurial intentions, activity and learning outcome. Education + Training, 56 (8/9), 795-813.

Van Gelderen, Marco, Kautonen, Teemu & Fink, Matthias. 2015. From entrepreneurial intentions to actions: Self-control and action-related doubt, fear and aversion. Journal of Business Venturing, 30 (2015), 655-673.

[/vc_tta_section][/vc_tta_accordion]