Introduction

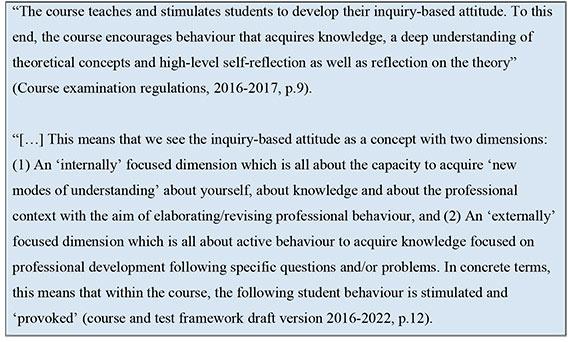

Current changes in society address new demands on professionals’ ability to respond to new and changing circumstances quickly and adequately (Coonen, 2006; Hargreaves & Fullan, 2012; 2002; OCW/EZ, 2009). This implies the necessity of continuous development to improve professional performance throughout the entire career. This general professional demand has consequences for teacher education (Darling-Hammond & Foundation, 2008; Scheerens, 2010). To support this lifelong professional learning, the development of an inquiry-based attitude (hereinafter: IA) is specifically recommended as a goal in teacher education (e.g. Cochran-Smith & Lytle, 2009). In Dutch teacher education at both initial and post-initial level, it is assumed that IA will allow teachers to create new knowledge of practice continuously with the aim to develop themselves as a professional and to improve their school context (Onderwijsraad, 2014). To be able to get more understanding about IA as a developable goal in teacher education, Meijer, Geijsel, Kuijpers, Boei and Vrieling (2016) conducted a multiannual empirical study and refined IA from an ill-defined global concept into a concept with reliable and valid characteristics. Their results indicated IA as a concept with two dimensions: an internal reflective dimension and an external knowledge-sourcing dimension. The internal dimension concerns intentional actions to acquire new professional modes of understanding and behaviour. The external dimension concerns intentional actions to gain new information and knowledge from relevant knowledge-sources. Our goal in this study was to create knowledge to support teacher educators’ in their pedagogical approaches to stimulate their students’ IA. However, the transfer of results from educational research into educational practice has proven to be complex (e.g.Broekkamp & van Hout-Wolters, 2007; OCW, 2011). To help bridge this gap, practice-based scientific mode-2 research design is presented as a research method that can help (Martens, Kessels, De Laat, & Ros, 2012). The assumption in this method is that partnership between researchers and practitioners will contribute to creating meaningful, generalisable knowledge and contribute to the transfer of this knowledge into practice. We therefore used this research design in our two-year follow-up study. In partnership with educators, we designed, tested and redesigned a professional development programme and we conducted a multiple case study. In this study (Meijer, Kuijpers, Boei, Vrieling, & Geijsel, in press) we gained insight into specific characteristics of professional development interventions that encourage teacher educators’ deep learning in stimulating IA-development of their students.

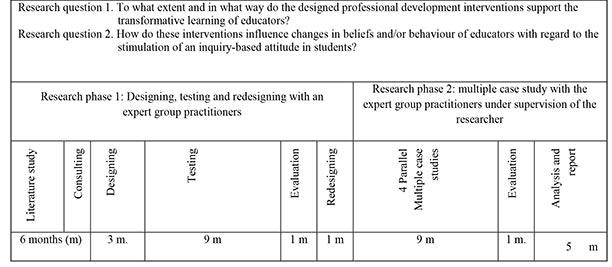

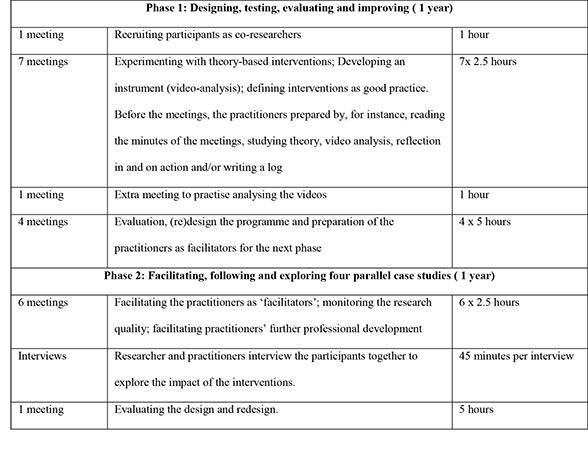

To our knowledge, there are few studies that provide specific insight into the design of practice-based scientific mode-2 research (hereinafter: mode-2 research) or into the actual impact of this methodology. To contribute to an understanding of how mode-2 research can help to bridge the gap between educational research and practice, this conceptual paper will reflect on how the partnership between the researcher and five educators resulted in creating practice-based scientific knowledge, professionalising teacher educators and simultaneously contributed to innovating teacher education practice. With this reflection, we aim to contribute to the development of mode-2 research as promoted in a research manifest on practice based scientific research (Martens et al., 2012). The study we are reflecting on is summarised in Table 1 and Table 2.

In what follows we first describe mode-2 research as a relatively new mode in social science and the general scientific requirements and usability criteria our research had to meet. Secondly, we report researchers role; recruiting practitioners and organising research meetings. Thirdly, we reflect from theoretical perspectives as to how and why our approach affected educators’ professional development and brought innovation to teaching practice. In conclusion, we present our working hypothesis on design principles in mode-2 research and discuss its complexity in design and the demands researchers must meet to monitor and facilitate simultaneously the quality of the research process and the learning of the practitioners.

1. Mode-2 research

Traditional methods of knowledge production and dissemination are the subject of debate in social science. Current scientific knowledge production does not transfer to practice adequately and opinions differ regarding the measures that should be taken to close the gap (Broekkamp & van Hout-Wolters, 2007). To bridge this gap, fundamental changes are suggested as a new research mode with regard to the interaction between science and society (Nowotny, Scott, & Gibbons, 2001). Social science production, in which socially robust knowledge is produced by social interventions in the context of application, was labelled by Gibbons et al. (1994) as Mode-2 research. Martens et al. (2012) promote this mode-2 research as an alternative to traditional educational research, in which randomised controlled trials still seem to be the golden standard. This, despite the fact that the complexity in educational research makes it impossible to control all variables (Cochran-Smith & Zeichner, 2010). Research based on randomised controlled trials aims to prove universal causal patterns in teaching and disparages the need for a stronger body of knowledge with practical, context-related relevance. The lack of knowledge with practical relevance is seen as one of the causes of the gap between science and practice. Hargreaves (1999) therefore even urged teachers to produce the knowledge they need by themselves. Martens et al. (2012) assume that research for which the questions are provided by practice – a partnership between researchers and practitioners – will contribute to creating meaningful, generalisable knowledge. From the perspective of learning, they argue that if practitioners participate in the knowledge creation process while participating in a practice-based scientific educational research in their own context, practical relevant knowledge will not only be created but it will also support the transfer of scientific knowledge into practice. Bronkhorst, Meijer, Koster, Akkerman and Vermunt (2013) found that collaboration with educators enabled the researcher to benefit from their expertise and that researchers’ position as a learner and researchers’ appreciation of the partnership impacts educators’ engagement ‘agency’ in the research . This means being an ‘agent’ and ‘owner’ instead being an ‘instrument’ or in other words ‘a tool for the researcher’ (p. 93). They found also that, compared to other research designs, collaboration supported the experience of research as an integrated part of everyday practice, which is also one of the goals in teacher education (Onderwijsraad, 2014). Researchers’ support of practitioner agency is thus seen as important because the more agency, the greater the chance that a solution will be found for the problem being researched (Bolhuis, Kools, Joosten-ten Brinke, Mathijsen, & Krol, 2012; Cochran-Smith & Lytle, 2009) and this will, as stated before, support the transfer of knowledge into practice.

1.1. Scientific requirements

Creating socially robust and practice-based educational scientific knowledge, under mode-2 conditions, has to meet the same generally accepted scientific standards as any other scientific research (Martens et al., 2012; Ros et al., 2012). However in mode-2 research, the relevance of the knowledge created is rooted in the (educational) context, in which the ‘problem’ occurred (Martens et al., 2012; Nowotny et al., 2001). A characteristic in this process of ‘local’ knowledge creation is to strive for external validity (i.e. generalisable insights) beyond the locus of knowledge production. Because practice-based research often works with small populations, it means that an attempt must be made, fitting within this type of search, to maximise generalisability without affecting the usability of the knowledge for the context in which the research took place (Ros et al., 2012; Verschuren, 2009). Furthermore, mode-2 research must be carried out in the wording of the scientific criteria that relate to the internal validity; controllability; cumulativeness and ethical aspects. The research must also meet the usability criteria with a view to the practice (Martens et al., 2012; Ros et al., 2012). The usability criteria define that the results must be accessible and understandable for the field of education; the results must be perceived as relevant and legitimate and the research must provide handles to improve educational practice.

1.2. Meeting scientific requirements in our study

In our two-year mode-2 research, we have secured internal validity by conducting it in the educational context in which the issue occurred. The study was executed in collaboration with an expert group of five teacher educators as co-researchers (Meijer et al., in press). The research process was characterised by iterative cycles of design, evaluation and redesign (McKenney & Reeves, 2013) and consisted of two phases: (1) a preparatory phase of designing, testing, evaluating and improving a theory-based professional development programme and (2) a main study phase in which the designed development programme was carried out. To build a strong partnership between the researcher and the participating practitioners, we followed Eri’s (2013) advice and involved them in constructing the design, and not only in testing the design, with the aim of supporting practitioners’ agency and ownership in the subject of the study.

To create generalisable knowledge we conducted the research as a parallel multiple case study (Swanborn, 2010) in four different teacher training courses. Four fairly homogeneous groups of teacher educators on four different teacher training courses at Bachelor and Master level at a professional university in the Netherlands were followed. The study resulted in clarification of the active ingredients of the designed interventions that supported the targeted development. We found that aligned ‘self-study’ interventions at personal, peer, and group level, guided by a trained facilitator, supported the aimed learning (Meijer et al., in press). To be able to reflect on this research from the perspective of partnership between researchers and teacher educators as co-researchers (hereinafter: expert group), we recorded and transcribed the research meetings (see table 2) with the expert group.

To meet the usability criteria we described our process of scientific knowledge construction and associated ethical aspects in a scientific publication and shared the results in the locus of the research. The way in which we further comply with the usability requirements is in fact seen in the focus of this reflective paper. In it, we look at how our collaboration with practitioners in the role of co-researcher resulted in socially robust scientific knowledge which contributed to professional development and is being implemented in practice. It should be noted that this implementation took place outside the scope of this research. This is because of the time that this implementation process took. In fact, the implementation process is still underway two years after the completion of this research.

2. Partnership between researcher and teacher educators in our study

The collaboration between practitioners and researchers is argued as a thriving force in developing new practices and educational change. To reflect on this assumption from our own research experience we will first successively report researchers role; recruiting practitioners and the research meetings between researcher and practitioners. Subsequently, in section 3, we will reflect on how our partnership between researcher and practitioners contributed to bridging the gap between science and practice. We reflect from theoretical perspectives on transfer of learning and development; practitioners’ knowledge creation and innovation and organisational learning.

2.1. Researcher

For mode-2 research it is important that the researcher(s) has coaching and consultancy skills in addition to research expertise and is able find balance between the relevance for the participating practitioners and the precision required by in scientific research (Martens et al., 2012). The researcher in this study (i.e. the first author) conducted research in her own professional context. She has an extensive experience as a teacher educator, trained supervisor/coach and is also responsible for the design of the professional Masters’ curriculum in the faculty where this research was conducted. This dialectic and simultaneous relationship between being a scholar and practitioner is an increasing phenomenon in educational research (Cochran-Smith, 2005). Before starting, and while conducting our research, the interwoven roles of the researcher were an explicit object of attention and reflection.

2.2. Recruiting the Practitioners

As pointed out above, besides creating practice-based scientific knowledge, the professional development of the collaborating practitioners is also one of the goals of mode-2 research. For this reason, we firstly based our research design on two preconditions in teacher-professionalisation, as reported by Van Veen, Zwart, Meirink and Verloop (2010): the subject of our study was in line with school policy and the participants were facilitated adequately by the management. Secondly, we decided to use the model of a professional learning community because this supports professional development (Lunenberg, Dengerink, & Korthagen, 2014; Van Veen et al., 2010), it supports innovation processes (Hargreaves & Fullan, 2012; Mourshed, Chijioke, & Barber, 2010) and it supports collaboration in designing, experimenting and re-designing (McKenney & Reeves, 2013; Van den Akker, Gravemeijer, McKenney, & Nieveen, 2006).

To recruit practitioners as co-designers and co-researchers in our research project, we organised a meeting with five experienced educators who were proposed by the management for practical reasons such as availability. We presented our research goal, basic design principles and the requirements that the participants had to meet. By being clear about our expectations of the participants’ qualities and commitment, we aimed to avoid drop-out on account of disappointment (e.g. Walk, Greenspan, Crossley, & Handy, 2015). First we presented our research goal as designing and redesigning a professional development programme based on theory and on practitioners’ knowledge and exploring which specific intervention characteristics support teacher educators’ professional development in stimulating students’ IA (Meijer et al., in press). We explained the importance of commitment in participating in a professional learning community during a two- year educational design-research within their own context. We also explained the importance of being an experienced teacher educator since we needed expert knowledge in designing a professional development programme. Experience was also important considering the plan that in the second phase of the study, the participants themselves would offer the designed programme to colleagues, and therefore we assumed that their credibility as a teacher educator should be beyond doubt. Furthermore, we highlighted the importance of being motivated to contribute to generalisable and reliable practice-based scientific knowledge by systematically, inimitably and accurately questioning their own practice. They also had to enjoy designing and redesigning interventions with the aim of improving them. Finally, we explained that they had to demonstrate commitment to participating in all the research meetings planned over the two years. Collaborating on this planning was presented as the first step in our partnership.

This meeting resulted in the voluntary participation of all five experienced (8-18 years) educators (hereinafter: expert group) aged between 43-58 and all female. They were facilitated with 90 hours of extra ‘professional development’ time over the two years, in addition to the standard annual time.

2.3. Research meetings

Before reflecting on ‘our’ partnership, we will give a short chronological overview of the research meetings between the researcher and the expert group (See Table 2, Overview of research meetings). All meetings can be characterised as ‘reflective dialogues’ (Mezirow & Taylor, 2009) between the researcher and the practitioners. Based on the practitioners’ wishes, we aligned our planning with the rhythm of our educational year. This meant no meetings during the busiest periods and not at the start and end of the year. The period between the meetings varied between two or three weeks.

3. Transfer of scientific knowledge into practice

To understand how collaboration with practitioners supported the transfer of scientific knowledge into practice, we firstly need to understand the underlying theories on the transfer of learning and professional development. Secondly, we need to comprehend the theories of practitioners’ knowledge creation and thirdly, we need to understand the theories of innovation and organisational learning. In these next sections, we will reflect – through the lenses of these theories – on our research journey, and illustrate our experiences with some vignettes.

3.1. Transfer of learning

The “changed and more experienced person is the major outcome of learning” (Jarvis, 2006, p. 132) is an important goal in mode-2 practice-based scientific educational research. In our research design, this learning concerned the development of teacher educators who participated as co-researchers. Since researchers in mode-2 research have to guide the participants’ learning and the transfer of this learning into educational practice, we built our research design on knowledge of learning theories in which the transfer of learning is a key concept.

Transfer of learning, and its underlying mechanisms, is still one of the most important educational research themes of the 21st century (e.g. Lobato, 2006). Thorndike (1906) introduced the concept of transfer and stated that the transfer of what is learned is dependent on the extent to which the new situations are the same as the original learning context. Thorndike conducted various empirical experiments and found that if an individual learns something in task A, it can be of benefit in task B if there are similarities between the two tasks. Although Thorndike’s view about transfer appeared to have been around for a century, later follow-up research showed that people can abstract things they have learned previously and subsequently apply this knowledge in contexts that are not obvious (e.g. Tomic & Kingma, 1988). However the transfer is stronger the more the contexts are alike. According to Piaget (1974), transfer occurs only if a measurement comes to the fore to show that what was learned had a demonstrable effect on the cognitive structure (knowing more) and that this knowledge can be operationalised in new situations. Piaget refers to this form of transfer as accomodating, by which he meant the capacity to adjust or transform familar strategies when a problem cannot (or can no longer) be resolved using the available tools and familiar methods. If this succeeds, previously acquired knowledge and insight is demonstrably transformed to a higher level.

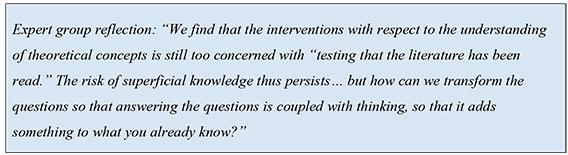

The theory of the transfer of knowledge to other contexts was further illuminated by Branson and Schwarz (1999) in their AERA award winning review of research into transfer. They described Thorndike’s original view on transfer as the ‘Direct application theory of transfer’ which means that a person can apply previous learning directly to a new setting or problem. Based on their review, Branson and Schwarz proposed an alternative view of transfer that broadens this traditional concept by “including an emphasis on people’s ‘preparation for future learning’” (p. 68). They explicated the implications of this view for educational practices and elaborated Broudy’s (1977) instructional procedures with the aim of supporting the ability to adapt existing knowledge, assumptions and beliefs to new situations. Bransford and Schwartz highlight that people “actively interact” with their environment to adapt to new situations “if things don’t work, effective learners revise” (Bransford & Schwartz, p. 83) (See for example vignette 1). This so-called active transfer involves openness to others’ ideas and perspectives and seeking multiple viewpoints that are also important as a characteristic of critical reflection.

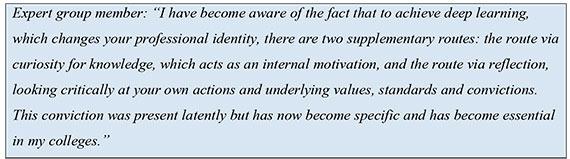

From the perspective of transfer, Illeris (2003, 2004, 2007; 2009) analyses leading theories of learning and differentiates four different learning types and looks at them in relation to their transfer capabilities. It is about mechanical learning, assimilating, accommodating and transforming. Each learning type is activated in different contexts, aims for different learning outcomes and varies according to the amount of energy learning requires. His learning theory rests on three different dimensions and two inseparable processes. He differentiates the cognitive (content), emotional (motivation) and social (interaction) dimension as well as the internal acquisition process in which new impulses are linked to earlier learning outcomes and the external interaction process that plays out between the learner, the teaching material and the social environment. According to Illeris (2014), professional learning already includes a change in practitioners’ work identity, the level of transformative learning. This happens only when the learner experiences a change in their own mental models with a perceivable impact on bringing about a change in attitude or behaviour. The individual then looks at the reality differently and also acts differently than previously (see for example vignette 2).

3.1.1. Supporting Practitioners’ Transformative Learning

To facilitate transformative learning Greeno (2006) calls for a learning environment in which stimulating and organising broad meaningful domain knowledge and automously founded actions are applied as two pro-transfer and inseparable factors. In this context, Kessels (2001) and Kessels and Keursten (2002) call for a knowledge-productive learning environment in which no educational material is prescribed, and instead research and reflection are the prime tools used to stimulate and facilitate meaningful learning. This is in line with the meta review by Taylor (2007) which indicates that accumulating personal learning experiences in a unique context about which there is critical reflection from various perspectives is one of the most powerful tools is promoting transformative learning. This is a process of communicative learning in which identifying and problematising ideas, convictions, values and feelings are critically analysed and given consideration. This requires a setting in which the participants dare to give themselves over to uncertainty and a certain degree of ‘discomfort’ so that they can learn personally. It is about daring mutual questioning of personal ‘truths’ and being prepared to modify existing paradigms on the basis of new insights. The shape transformative learning takes in education is in part dependent on the lecturer’s personal ideas about learning theories combined with the understanding of the reciprocal relationship between: (life) experience; critical reflection; dialogue; holistic orientation; context understanding and authentic relationships (Mezirow & Taylor, 2009). “Transformative learning is always a combination of unlearning and learning” (Bolhuis, 2009, p. 62). It is a radical process of falling down and getting back up again. According to Bolhuis, the unlearning element receives too little attention in research into and the forming of theories about learning. The helping hands that are offered with regard to ‘unlearning’ are implicit and are focused on reconstructing mental models and experimenting with new behaviour that can respond to behaviour and context through repetition and reflection.

In summary, this means that if mode-2 practice-based scientific educational research wants to contribute to the professionalisation of teachers, the research design must be based on ideas about learning theories with respect to the level of learning that is intended. In research into the professional beliefs and behaviour of the educator, a research setting in which transformative learning by the practitioners is facilitated is one of the design principles. This means that a research setting that is productive to knowledge is created, one which encourages and facilitates shared interactive research and the (re-)development of practical knowledge, beliefs and behaviour from different perspectives, with the aim of contributing to creating a ‘changed and more experienced person’ (see for example vignette 2).

Looking back over our research, we can typify our design of the learning environment in which the researcher and educators design and research together as a learning environment in which various levels can be learned. The accent in this was (1) having reflective dialogue which was dominated by: obtaining conceptual clarity about key concepts and the significance of this for practical actions and research into personal beliefs and the impact of these on actions; (2) the design of a theory-based analysis tool that, over a number of cycles, we ‘tested, reflected on, modified and again tested until we could work satisfactorily with it and were confident that the participants in the follow-up study could deal with effectively; (3) the design of interventions at ‘individual, peer and group level’ (Meijer et al., in press) via cycles of testing, reflecting on what worked, why it worked and how it could be improved; and (4) the design of a coherent professional development programme based on the interventions with the associated supporting materials and the basic premises of supporting learning from the participants. Because the practitioners researched with the researcher what interventions had an impact on their own development as well as how and when, they created new knowledge about professional development. They also integrated conceptual scientific knowledge about the subject of the research, ‘stimulating the inquiry-based attitude’, into their own educational repertoire.

3.2. Supporting Practitioners’ knowledge productivity

Following on from European and Americans examples (e.g. Cochran-Smith & Lytle, 2009; Loughran, 2007; Pickering et al., 2007), in the Dutch educational context and teacher training, we are increasingly seeing practitioner research used as a professional learning strategy to support individual and organisational learning. The teachers do their own research in their own context and the research itself as seen as an intervention (Bolhuis et al., 2012). According to Bolhuis et. al, practically-focused research by professionals contributes to more conscious consideration about the aims and effects of the work and promotes this approach where professionals create practical knowledge and use other people’s knowledge more in their work. The concept of practitioners’ knowledge productivity as a process in which new knowledge is created to contribute to innovation in the workplace was introduced by Kessels (1995; 2001). It refers to using relevant information to develop and improve products, processes and services. Supporting processes of practitioners’ knowledge creation requires expertise, such as “making tacit knowledge explicit, facilitating work and teambuilding, and supplying mentors and coaches with appropriate guidance abilities” (Kessels, 1998, p. 2). Knowledge productivity refers to ‘breakthrough’ learning’ which means that learners develop new approaches and are able to break with the past (Verdonschot, 2009). Both Kessels and Verdonschot believe that innovation processes are denoted as social communicative processes in which participants work in collaboration, whereby the quality of the interaction is important and should provide access to each other’s knowledge and connect these (see for example vignette 3). Paavola, Lipponen and Hakkarainen (2004) introduced the knowledge creation metaphor as a learning metaphor that concentrates on mediated processes of knowledge creation. A learning model based on knowledge-creation conceptualises “learning and knowledge advancement as collaborative processes for developing shared objects of activity […] toward developing […] knowledge” (p. 569)

3.2.1. Collaborative learning

In collaborative learning, the literature makes frequent reference to professional learning communities, group learning or learning from peers, and is seem as the most powerful driver for educational innovations (Hargreaves & Fullan, 2012; Mourshed et al., 2010). The concept of a professional community is multidimensional in nature and can be unpacked as practitioners’ peer learning with the goal of developing a shared vision that provides a framework for shared decision making on meaningful practice questions (see for example vignette 4). The aim is to improve practice from the perspective of collective responsibility, in which both group and individual learning are promoted. (Hord, 1997; Stoll, Bolam, McMahon, Wallace, & Thomas, 2006).

The positive impact of collaborative learning methods is convincingly present in research literature. The meta analysis by Pai, Sears and Maeda (2015) showed that compared to individualistic learning methods, learning in small groups ( 2-5 participants) promotes students’ acquisition of knowledge and has also positive effects on increasing the transfer of students’ learning experiences and outcomes into practice. From the perspective of cognitive load theory, that considers a collaborative learning group as an information processing system (Janssen, Kirschner, Erkens, Kirschner, & Paas, 2010), students working in a group outperform students working individually, because a group has more processing capacity than individual learners. Sharing the cognitive load increases the cognitive capacity to understand the learning objectives at a deeper level (Kirschner, Paas, & Kirschner, 2009).

Pai, Sears and Maeda (2015) found that the positive interdependence between the group members, interpersonal skills and carefully structured interaction contributed effectively to collaborative learning achievements. There is also general agreement that the reflective dialogue plays a key role in the interaction in collaborative learning (e.g. Fielding et al., 2005; Lomos, Hofman, & Bosker, 2011) and that critical friendship, with the emphasis on ‘friendship’, in the sense of equality, trust, openness and vulnerability (Schuck, Aubusson, & Buchanan, 2008) is a prerequisite for collaborative learning. Personal commitment, as in the sense of learner engagement (see for example vignette 5), is indicated as another precondition to resolve complex practice-based problems and find acceptable solutions. (Bolhuis et al., 2012; Fielding et al., 2005)

In their exploration of the relation between teacher learning and collaboration in innovative teams, Meirink, Imants, Meijer and Verloop (2010) found that collaboration in teams that focused on both “sharing of ideas and experiences” and “sharing identifying and solving problems” contributed to a higher level of interdependence. Collegial interaction that can be typified as ‘joint work’ is indicated as interaction with the highest level of interdependence. This is in line with other findings from research into factors that influence the transfer of good practice (e.g. Fielding et al., 2005). In this study, the transfer of good practise is seen as ‘joint practice development’ which depends on relationships, institutional and teacher identity, having time, and most important learner engagement. The importance of “the quality of relationships between those involved in the process” (p. 3) is highlighted because the transfer of practice is relatively intrusive and hard to achieve.

In summary, this means that supporting practitioners’ knowledge productivity during mode-2 research requires a research design incorporates the theoretical ideas regarding collaborative workplace learning. Here, the practitioners use practice-focused as a professional learning strategy and not just as a tool to create knowledge.

Looking back on the knowledge productivity of the educators in our research design, we see strong correlations with, for example, the practitioner research self-study method (Loughran, 2007; Lunenberg, Zwart, & Korthagen, 2010). The aim of our research is very close to the central goal of the self-study methodology. This goal is to uncover deeper understandings of the relationship between teaching and learning about teaching, with the aim of improving the alignment between intentions and actions in the practitioners’ teaching practice. Like the self-study approach, our research design strongly appeals to individuals’ scholarly notions and qualities, where the systematic collation and analysis of personal data in a personal context supports a personal deeper professional understanding that can be shared with other colleagues. However, where we differ explicitly from the self-study approach is that our research design centred around ‘collective’ learning in multiple settings with the aim of creating a collective deeper understanding and generalizable scientific knowledge, and implementing this new knowledge into the practice of teacher educators. The importance of well-guided collaborative knowledge creation in small-peer groups is thereby emphasised by the expert group. The expert group highlighted the importance of flexible research guidance that is aligned with the ‘reality of the daily working context’ as a precondition to staying motivated to participate in this research project (see for example vignette 6).

3.3. Innovation in education

As well as professional teaching, mode-2 research also aims for innovation in the professional context. Therefore it is relevant to understand the relationship between individual and collective organisational learning (Argyris, 2002; Senge, Cambron-McCabe, Lucas, Smith, & Dutton, 2012). Innovation in education programmes is a complex, broad concept and concerns multiple relations and dimensions within multiple programme components. For a definition of what we can understand innovation in education, we use Waslander’s (2007) description in her review of scientific research on sustained innovation in secondary education. To her, an innovation is a set of activities which together comprise a concept or an idea which if implemented improves practice. An innovation is something ‘new’ that has added value for the future. Further, there is only an innovation of this ‘news’ manifests itself in people’s behaviour and is embedded in their day-to-day routine.

Innovations at the organisation level always relate to relationship between individual and collective learning and successfully triggering collective learning is a first step towards innovating. The research by Peck, Gallucci, Sloan and Lippincott (2009) into teacher education practices shows that the problems related to individual practice (raised by new policies) are often the trigger for faculty (collective) learning. Even though collective learning still delivers such well designed interventions and knowledge, it is no guarantee of successful implementation at the level of the organisation (Verdonschot, 2009). Based on her meta analysis of innovation practices, Verdonschot established that the skills and ambition of the individual implementing the intervention influence its success. In addition, the new knowledge that is to be integrated must be well-timed, relevant and appropriate (Eraut, 2004, 2007; Peck et al., 2009). If the knowledge was not acquired in a personal context, but through formal learning such as, for example, schooling, it often has to be transformed to the personal situation because the new knowledge doesn’t fit the actual situation in which it is required. To integrate the new knowledge requires practitioners’ meta cognitive skills in transforming knowledge and skills to the personal situation.

3.3.1. Supporting innovation in education

In supporting professional learning that is focused on innovating, it is essential to facilitate the generation of new reality constructions (Homan, 2005). Generating new reality constructs is central to the theory on organisational learning in the familiar work by Argyris and Schön (1978) and is aligned with the previously discussed theory on transfer of learning. Argyris (1992; 2002) differentiates between single-loop learning and double-loop learning. With single-loop learning, a lot is learned but nothing is learned about how to learn better. It is generally about solutions that are more of the same. Single-loop learning will therefore not contribute to innovations because it concerns only correcting errors without altering underlying governing values. To resolve complex problems for which new solutions are needed, double-loop learning is needed. This means calling on the ability to fundamentally think the problem through and learn from this through critical reflection. Argyris stated that to change organisational routines with success, organisational and individual double-loop learning processes should both be encouraged. In his opinion, it is impossible to change organisational routines without changing individual routines, and vice versa. Senge, Cambron-McCabe, Lucas, Smith and Dutton (2012) talk in this context about fundamental changes in mental models, systems and interactions which are a prerequisite to redesigning and changing the current situation. To support double loop-learning, Argyris calls for an increase in people’s capacity “to confront their ideas, to create a window into their minds, and to face their hidden assumptions, biases, and fears by acting in these ways toward other people” (2002, p. 217). He highlights the importance of encouraging self-reflection and advocating personal principles, values, and beliefs in a way that invites inquiry into them. This is in line with Eraut’s research (2004, 2007) in which he emphasises the critical importance of support and feedback in enhancing organisational learning, especially within a working context of good relationships and supporting managers. In addition, opportunities for working alongside others or in groups, where it is possible to learn from one another, are important.

In summary, this means that if mode-2 practice-based scientific educational research wants to help in innovating educational context, more is needed than stimulating double-loop learning by practitioners during joint design and research. Encouraging transfer between individual and collective learning and securing its implementation in the professional context requires a research design that is based on innovation theories that are leading in the monitoring of this complex form of learning.

Looking back over our research, we have experienced that the transfer of personal learning into organisational learning and innovation is highly complex and time-consuming. In our opinion, a well-designed implementation plan that is guided by principles from theories on organisational learning and innovation is needed prior to the start of the research. In our view, this plan must include management support and implementation facilities to ensure that the implementation doesn’t come to a halt when the researcher leaves.

In the study we are reflecting on, the researcher had a management position in two of the four participating educational settings and was able to influence the organisational policy concerning educating teachers and the demands the educators have to meet. In these two settings, our mode-2 research resulted in a successful transfer of scientific knowledge into our practice policy (see for example vignette 7).

In the other two settings, our research design was only successful from the perspectives of knowledge creation and professional development. Once the (co-) researcher had left, further implementation came to a halt. Our explanation is that having an implementation plan that is supported by the management (e.g. Eraut, 2004, 2007; Van Veen et al., 2010) is a prerequisite to implementing the innovation at the organisational level. We recommend that that if the researcher is not to execute the implementation plan personally, this should be done by an engaged practitioner who, in line with Verdonschot’s research (2009), has the courage, ambition and mandate to make the implementation a success. Looking back on our innovation we can see that, like many other innovations, it was triggered by new policy (Peck et al., 2009). This policy concerns the ambition of the Dutch Educational Council (2014) to promote the development of an inquiry-based attitude on the part of teachers.

4. Working hypothesis concerning design principles in mode-2 research

This conceptual paper is a reflection of our previous two-year mode-2 research journey (Meijer et al., in press) in which our partnership between researcher and practitioners successfully contributed to bridging the research-to practice-gap in education. That research concerned a multiple case study as part of which we worked with five experienced educators to design, test and explore a professional development programme. Our reflection shows that the partnership in our research helped to create socially robust scientific knowledge and that this collaboration contributed to the transfer of the knowledge created into the practice in which the research was conducted. The new knowledge was not just integrated into the practitioners’ actions, in two of the four settings where the research was conducted, it was also translated into internal policy documents. These policy documents are definitive in ensuring curriculum innovation and thus the required educational behaviour in the setting in which the researcher works.

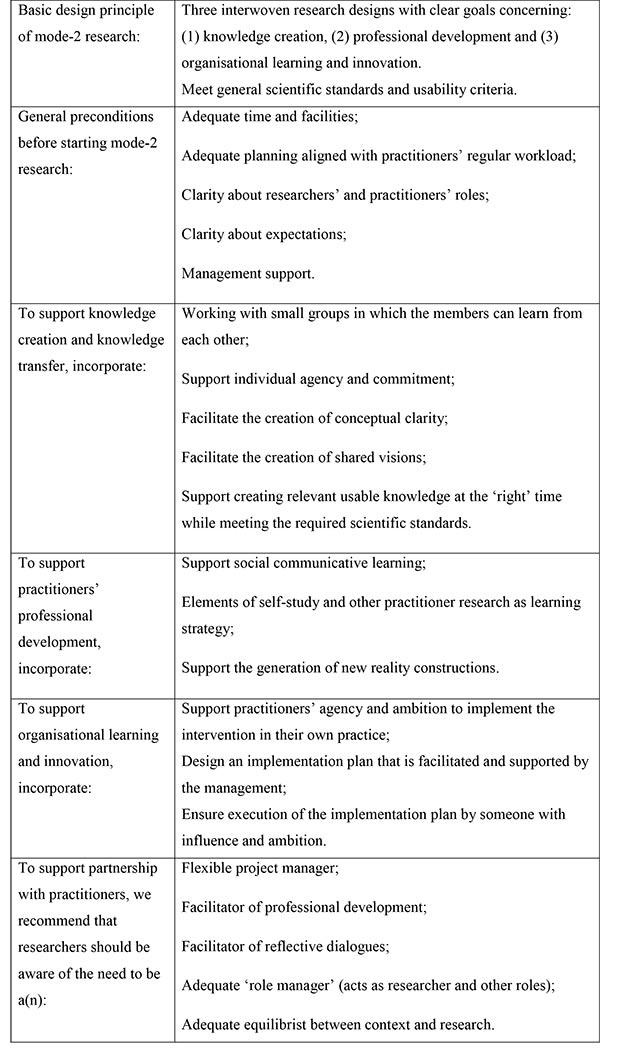

Our contribution in shaping the theory regarding the design of mode-2 research comprises firstly the finding that partnership between the researcher and practitioners in creating practice-based scientific knowledge succeeds in closing the gap between theory and practice if the research design includes the objectives and a theoretically-based approach to both practitioners’ knowledge creation, practitioners’ development and the proposed organisational learning and innovation. Secondly our reflection resulted, from various theoretical perspectives of the partnership with practitioners, in concrete design principles, preconditions and recommendations for supporting and guiding practitioners during mode-2 research. We have set these out in the table below (see Table 3) and these can be seen as a working hypothesis for designing and guiding this kind of research. Allocation to the categories used is not a distinction because some of the recommendations apply within multiple categories.

To summarise: in this conceptual paper, we have reflected on the theoretical aspects of transfer of learning; professional development; practitioners’ knowledge creation; innovation and organisational learning on how partnership with practitioners can help in bridging the gap between theory and practice.

Our reflections have highlighted the importance of having three interwoven research designs in mode-2 research: (1) one design concerning the scientific knowledge creation process based on practitioners’ knowledge creation; (2) one design concerning the practitioners’ learning support in knowledge creation, professional learning and knowledge transfer and (3) and one design that guarantees implementation into practitioners’ practice at the organisational level. To gain a deeper scientific understanding in critical design variables in mode-2 research which at the same time help to create scientific practice-based knowledge, professionalise practitioners and ensure innovation, we recommend that mode-2 researchers write conceptual papers from the perspective of three interwoven designs to allow further meta analysis to be carried out in the future. We also advise further investigation into the qualities a mode-2 researcher must demonstrate as a facilitator of professional development and innovation. The researchers can use the design principles we have proposed as a working hypothesis for designing and guiding their own mode-2 research. Follow-up research into these design principles can support deeper understanding of how mode-2 research in education can bridge the gap between theory and practice.

Corresponding Author

Marie-Jeanne Meijer, PHD-student, Curriculum director at Windesheim University of Applied Sciences, Movement & Education, The Netherlands, mj.meijer(at)windesheim.nl

Author

Marinka Kuijpers, PHD, Professor at Welten Institute, Open University, The Netherlands, marinka.kuijpers(at)ou.nl

[vc_tta_accordion active_section=”0″ no_fill=”true” el_class=”lahteet”][vc_tta_section title=”Bibliography” tab_id=”1458134585005-b3f22396-5506″]

Argyris, C. (1992). On Organizational Learning. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers.

Argyris, C. (2002). Double-loop learning, teaching, and research. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 1(2), 206-218.

Argyris, C., & Schön, D. A. (1978). Organizational learning: A theory of action perspective (Vol. 173): Addison-Wesley Reading, MA.

Bolhuis, S. (2009). Leren en veranderen. Bussum: Coutinho.

Bolhuis, S., Kools, Q., Joosten-ten Brinke, D., Mathijsen, I., & Krol, K. (2012). Praktijkonderzoek als professionele leerstrategie in onderwijs en opleiding.

Bransford, J. D., & Schwartz, D. L. (1999). Rethinking Transfer: A Simple Proposal With Multiple Implications Review of research in education (Vol. 24, pp. 61-100).

Broekkamp, H., & van Hout-Wolters, B. (2007). The gap between educational research and practice: A literature review, symposium, and questionnaire. Educational Research and Evaluation, 13(3), 203-220.

Bronkhorst, L. H., Meijer, P. C., Koster, B., Akkerman, S. F., & Vermunt, J. D. (2013). Consequential research designs in research on teacher education. Teaching and Teacher Education, 33, 90-99.

Broudy, H. S. (1977). Types of knowledge and purposes of education. Schooling and the acquisition of knowledge, 1-17.

Cochran-Smith, M. (2005). Teacher educators as researchers: Multiple perspectives. Teaching and teacher education, 21(2), 219-225.

Cochran-Smith, M., & Lytle, S. L. (2009). Inquiry as stance: Practitioner research for the next generation. New York: Teachers College Press.

Cochran-Smith, M., & Zeichner, K. (2010). Studying teacher education: The report of the AERA panel on research and teacher education: Routledge.

Coonen, H. (2006). De leraar in de kennissamenleving: beschouwingen over een nieuwe professionele identiteit van de leraar, de innovatie van de lerarenopleiding en het management van de onderwijsvernieuwing: Garant.

Darling-Hammond, L., & Foundation, G. L. E. (2008). Powerful learning: What we know about teaching for understanding: Jossey-Bass San Francisco.

Eraut, M. (2004). Informal learning in the workplace. Studies in Continuing Education, 26(2), 247-273.

Eraut, M. (2007). Learning from other people in the workplace. Oxford Review of Education, 33(4), 403-422.

Eri, T. (2013). The best way to conduct intervention research: methodological considerations. Quality & Quantity, 47(5), 2459-2472.

Fielding, M., Bragg, S., Craig, J., Cunningham, I., Eraut, M., Gillinson, S., . . . Thorp, J. (2005). Factors influencing the transfer of good practice.

Gibbons, M., Limoges, C., Nowotny, H., Schwartzman, S., Scott, P., & Trow, M. (1994). The new production of knowledge: The dynamics of science and research in contemporary societies: Sage.

Greeno, J. G. (2006). Authorative, Accountable Positioning and Conected, General Knowing: Progressive Themes in Understanding Transfer. The Journal of the Learning Sciences, 15(4), 537-547.

Hargreaves, A., & Fullan, M. (2012). Professional capital: Transforming teaching in every school: Teachers College Press.

Hargreaves, D. H. (1999). The knowledge‐creating school. British journal of educational studies, 47(2), 122-144.

Homan, T. H. (2005). Organisatiedynamica: Theorie en praktijk van organisatieverandering.

Hord, S. M. (1997). Professional learning communities: Communities of continuous inquiry and improvement.

Illeris, K. (2003). Towards a contemporary and comprehensive theory of learning. International Journal of Lifelong Education, 22(4), 396-406.

Illeris, K. (2004). The Three Dimensions of Learning: Roskilde University Press.

Illeris, K. (2007). How we learn : learning and non-learning in school and beyond (2nd rev. English ed ed., pp. XIII, 289). London: Routledge.

Illeris, K. (2009). Transfer of learning in the learning society : How can the barriers between different learning spaces be surmounted, and how can the gap between learning inside and outside schools be bridged? International journal of lifelong education (Vol. 28, pp. 137-148).

Illeris, K. (2014). Transformative learning and identity. New York: Routledge.

Janssen, J., Kirschner, F., Erkens, G., Kirschner, P. A., & Paas, F. (2010). Making the black box of collaborative learning transparent: Combining process-oriented and cognitive load approaches. Educational psychology review, 22(2), 139-154.

Kessels, J. (2001). Learning in organisations: a corporate curriculum for the knowledge economy. Futures, Vol. 33, 497-506.

Kessels, J., & Keursten, P. (2002). Creating a Knowledge Productive Work Environment. Lifelong Learning in Europe, 7(2), 104-112.

Kessels, J. W. M. (1995). Opleiden in arbeidsorganisaties. Het ambivalente perspectief van de kennisproductiviteit [Training in organizations: The ambivalent perspective of knowledge productivity]. Comenius, 15(2), 179-193.

Kessels, J. W. M. (1998). The development of a corporate curriculum: the knowledge game. Gaming/Simulation for Policy Development and Organizational Change, 29(4), 261-267.

Kessels, J. W. M. (2001). Verleiden tot kennisproductiviteit [Tempting towards knowledge productivity]. Inaugural lecture. Enschede.

Kirschner, F., Paas, F., & Kirschner, P. A. (2009). A cognitive load approach to collaborative learning: United brains for complex tasks. Educational Psychology Review, 21(1), 31-42.

Lobato, J. (2006). Alternative Perspectives on the Transfer of Learning: History, Issues, and Challenges for Future Research. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 15(4), 431-449.

Lomos, C., Hofman, R. H., & Bosker, R. J. (2011). Professional communities and student achievement–a meta-analysis. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 22(2), 121-148.

Loughran, J. (2007). Researching teacher education practices responding to the challenges, demands, and expectations of self-study. Journal of teacher education, 58(1), 12-20.

Lunenberg, M., Dengerink, J., & Korthagen, F. (2014). The Professional Teacher Educator. Roles, Behaviour, and Professional Development of Teacher Educators (Vol. 13). Rotterdam, Boston, Taipei: sense Publishers.

Lunenberg, M., Zwart, R., & Korthagen, F. (2010). Critical issues in supporting self-study. Teaching and Teacher Education, 26(6), 1280-1289.

Martens, R., Kessels, J., De Laat, M., & Ros, A. (2012). Praktijkgericht wetenschappelijk onderzoek. Practice-based scientific research. Research manifest LOOK. Heerlen, the Netherlands: Open Universiteit Nederland.

McKenney, S., & Reeves, T. (2013). Conducting educational design research: Routledge.

Meijer, M., Geijsel, F., Kuijpers, M., Boei, F., & Vrieling, E. (2016). Exploring teachers’ inquiry-based attitude. Teaching in Higher Education, 21(1), 64-78.

Meijer, M., Kuijpers, M., Boei, F., Vrieling, E., & Geijsel, F. (in press). Professional Development of Teacher-Educators towards Transformative Learning. Professional Development in Education.

Meirink, J. A., Imants, J., Meijer, P. C., & Verloop, N. (2010). Teacher learning and collaboration in innovative teams. Cambridge Journal of Education, 40(2), 161-181.

Mezirow, J., & Taylor, E. W. (2009). Transformative learning in practice: Insights from community, workplace, and higher education. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Mourshed, M., Chijioke, C., & Barber, M. (2010). How the world’s most improved school systems keep getting better. Retrieved from London:

Nowotny, H., Scott, P., & Gibbons, M. (2001). Re-thinking science: Knowledge and the public in an age of uncertainty: SciELO Argentina.

OCW/EZ. (2009). Naar een robuuste kenniseconomie, Brief aan de Tweede Kamer. Den Haag.

Onderwijsraad. (2014). Meer innovatieve professionals. Den Haag.

OCW. (2011). Nationaal Plan Toekomst Onderwijswetenschappen. Den Haag: ministerie van OCW.

Paavola, S., Lipponen, L., & Hakkarainen, K. (2004). Models of innovative knowledge communities and three metaphors of learning. Review of educational research, 74(4), 557-576.

Pai, H.-H., Sears, D. A., & Maeda, Y. (2015). Effects of small-group learning on transfer: A meta-analysis. Educational Psychology Review, 27(1), 79-102.

Peck, C. A., Gallucci, C., Sloan, T., & Lippincott, A. (2009). Organizational learning and programme renewal in teacher education: A socio-cultural theory of learning, innovation and change. Educational Research Review, 4(1), 16-25.

Piaget, J. (1974). The construction of reality in the child. New York: Ballantine Books.

Pickering, J., Daly, C., Pachler, N., Gowing, E., Hardcastle, J., Johns-Shepherd, L., . . . Simon, S. (2007). New designs for teachers’ professional learning: Institute of Education, University of London London.

Ros, A., Amsing, M., Ter Beek, A., Beek, S., Hessing, R., Timmermans, R., & Vermeulen, M. (2012). Gebruik van onderwijsonderzoek door scholen. Onderzoek naar de invloed van praktijkgericht onderzoek op schoolontwikkeling. Retrieved from s Hertogenbosch:

Scheerens, J. (Ed.) (2010). Teachers Professional Development, Europe in international comparison. Luxembourg: European Commission.

Schuck, S., Aubusson, P., & Buchanan, J. (2008). Enhancing teacher education practice through professional learning conversations. European journal of teacher education, 31(2), 215-227.

Senge, P. M., Cambron-McCabe, N., Lucas, T., Smith, B., & Dutton, J. (2012). Schools that learn (updated and revised): A fifth discipline fieldbook for educators, parents, and everyone who cares about education: Crown Business.

Stoll, L., Bolam, R., McMahon, A., Wallace, M., & Thomas, S. (2006). Professional learning communities: A review of the literature. Journal of Educational Change, 7(4), 221-258.

Swanborn, P. (2010). Case study research: What, why and how? : SAGE Publications Limited.

Taylor, E. W. (2007). An update of transformative learning theory: a critical review of the empirical research (1999–2005). International Journal of Lifelong Education, 26(2), 173 – 191.

Thorndike, E. L. (1906). Principles of teaching. New York: Seiler.

Tomic, W., & Kingma, J. (1988). Accelerating Intelligence Development through Inductive reasoning Training. Advances in Cognition and Educational Practice, 5, 291-305.

Van den Akker, J., Gravemeijer, K., McKenney, S., & Nieveen, N. (2006). Educational design research: Routledge.

Van Veen, K., Zwart, R., Meirink, J., & Verloop, N. (2010). Professionele ontwikkeling van leraren. Retrieved from Leiden:

Verdonschot, S. G. M. (2009). Learning to innovate: a series of studies to explore and enable learning in innovation practices: University of Twente.

Verschuren, P. (2009). Praktijkgericht onderzoek. Ontwerp van organisatie-en beleidsonderzoek [Practice-oriented research. Design of organisation and policy research]. The Hague, the Netherlands: Boom Lemma.

Walk, M., Greenspan, I., Crossley, H., & Handy, F. (2015). Mind the Gap: Expectations and Experiences of Clients Utilizing Job‐Training Services in a Social Enterprise. Annals of Public and Cooperative Economics, 86(2), 221-244.

Waslander, S. (2007). Leren over innoveren. Overzichtsstudie van wetenschappelijk onderzoek naar duurzaam vernieuwen in het voortgezet onderwijs.

[/vc_tta_section][/vc_tta_accordion]