Authors: Minna Scheinin & Mauri Kantola.

Introduction

The purpose of the present article is to discuss the characteristics of an online learning network of experts. Further, the article discusses how to create a social community and interaction between people who share the same interest topics and the concerns attached to them. Expert groups often evolve within a project and work well through the lifecycle of the project. However, it is generally experienced that a group of experts is often dispersed at the end of the project. The participants easily lose interest towards collaboration when the funding is finished and the formal structure of the collaboration comes to its end. Can we find any personal characteristics of the participants or features of an expert group, which could support the cooperation to outlive the time span of a project? These are the main focus areas of the present article.

Background and Framework

The study is carried out within the framework of the Finnish project eAMK, the aim of which is among other things to develop a mutual digital study tray for all universities of applied sciences (UASs). The eAMK project has largely discussed the future visions of a national study offering together with the visions of the future learning ecosystems (Scheinin 2017). This is ”a golden age for universities to redefine their role in the environment of ubiquitous knowledge and intelligence” (Mulgan 2018, 175). In order to reach the project aim, ie. a flexible national online study tray of all Finnish UASes, it is crucial that the participants of the project work well together and are able to mutually understand the importance of national cooperation. These matters can be looked at by mirroring the discussions about Higher Education development on several levels. The top-down approach starts from the ideas for the future by the European Union. The fact that digitalization enables us to easily share knowledge and experiences has led to the discussions about the role and structure of HE institutions. The focus on teaching is shifting towards learning: who is teaching and where does learning take place, who is responsible for learning and what is the role of the institutions? The EU renewed agenda for higher education (COM 2017) lists three priorities for action:

- Promoting excellence in skills development

- Ensuring higher education institutions to be able to contribute to innovations

- Supporting effective and efficient higher education systems

All these are crucial focus areas when learning is going to online and the institutions aim to offer high-quality online courses for the students.

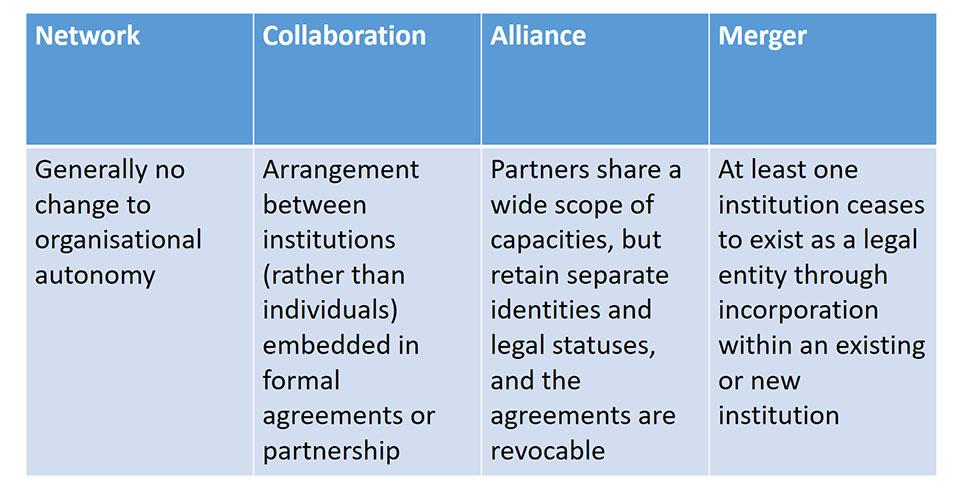

OECD introduces the concept of networks within higher education on the basis of the strength of cooperation. From the looser typed of cooperation towards the more structured or intensive, they are listed as network, collaboration, alliance and merger (Williams, 2017, p.4).

This approach is valuable to understand for the present eAMK project. As we are acting nationally towards a mutual online study offering, we need to understand the importance of the level our cooperation and if it has the potential to be intensified. In Finland, the universities of applied sciences are very autonomous and self-regulating as far as the structure and curricula are concerned. Therefore, it is not always a straightforward matter to unify practices or collaborate across the institutions. The structures and the funding systems do not support flexibility.

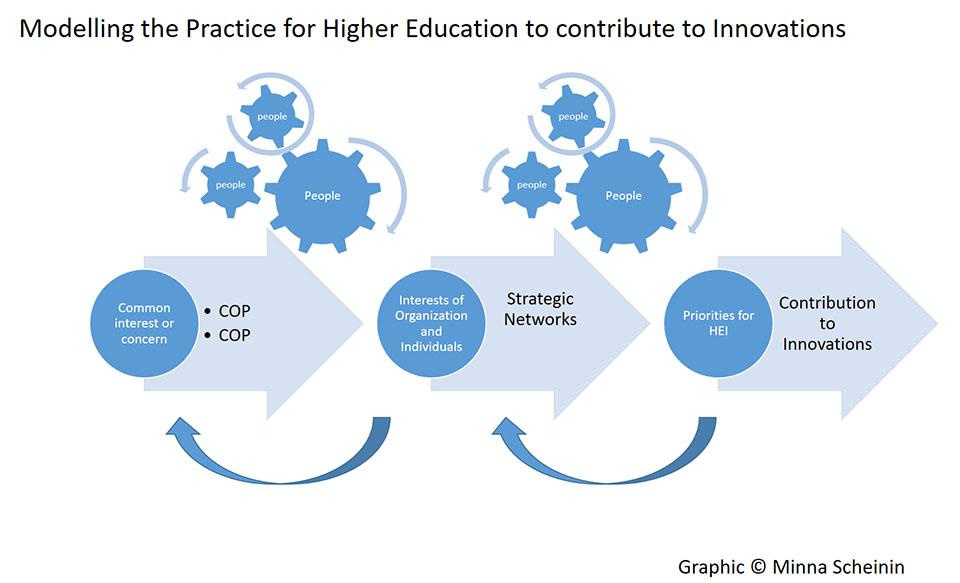

The Finnish Ministry of Education and Culture launched a vision for Higher Education in Finland 2030 (OKM 2018). This vision emphasizes a strong and multifaceted higher education as a change agent in the society and business structure, better ability to foresee, react and innovate. All this supports the brave initiatives to act differently and to find new paths for designing learning. This is where we understand that the national effort for the online study tray finds its rationale on the ministerial level. Finally, the concept of cooperation and networks is important not only by giving a framework for the different structural models for HEIs. It also covers another crucial point, namely how strategic networks are built and how they operate. Kantola et al. (2011, p. 185) argue that discussions about strategic networks are not only the in interest of the organizations but also of individuals. This means that it is justified to focus also on people, not only on structures. Cooperation is also noticed in several learning and strategic approaches of the HEIs, for example the innovation pedagogy developed at Turku University of Applied Sciences (Konst et al. 2018).

What has been said above, is summarized in a Figure 2 as follows:

Reading from right to left, in order to contribute to innovations, HEIs should look at their strategic networks as well as the people who operate. How people operate in an expert group can be studied with the help of the model called Communities of Practice (COI). This will be focused on in the next chapter.

Expert group as a community of practice

Communities of practice (COI) is one model of an environment, in which a group of ”people share a concern, a set of problems or a passion about a topic, and who deepen their knowledge and expertise in this area by interacting on ongoing basis “ (Wenger et al. 2002). Such communities also foster mutual trial and understanding about the facts that tie together the participants (Palonen et al. 2017, p. 54). In the principals for cultivating COI Wenger brings the following elements into discussion: COIs are organic and the design elements should be catalysts for the evolution. The participation can occur on different levels and for different reasons. All live communities have a coordinator. In dynamic communities both private and public connections take place. What is important for the communities to thrive is that they deliver value for the organization, as well as for the teams and members of the community. Successful communities bring both new ideas as well as familiar topics into discussion. Finally, the communities also have a rhythm similarly as other everyday life (Wenger 2002, pp. 49‒64). We use the model of COI for further develop the evolving learning network of experts.

Method

The present study was carried out within the eAMK project. The aim of the project, the mutual learning platform, was opened in August 2018 under the name of CampusOnline.fi. It is based on the concept of the summer portal of the UASs, which has been organized for three summers. In the autumn 2018, a total of 68 courses were provided. The teachers of these courses, together with the project participants, are members of the evolving learning expert group studied here. These members are in different phases of their professional development in e-learning: less experienced teachers as well as experienced e-learning teachers, who acted as coaches and mentors within the group. All teachers were trained with a series of webinars concentrating on the good quality of e-learning. After the webinars, a two-day F2F seminar was organized, where the course materials were discussed and peer-assessed on a practical level in smaller groups. At this point, we carried out a questionnaire about the characteristics of the learning group of experts, which we considered had been evolved. The questionnaire was sent to 100 participants of the seminar and we received 44 answers.

Results

The aim of the questionnaire intervention was to study the characteristics of a learning network of experts and how such groups evolve digitally. We were also interested in the lifecycle of digital groups, when such consortia are built around a project and whether an expert group can outlive the life span of a project.

We studied what kind of people we had in the group with regard to how they experience themselves as undertaking new tasks. We found out that the participants are always enthusiastic about finding new ways of acting. They like to try out new things and the uncertainty does not seem to have an effect on their motivation and activity. The participants also experienced that the expert group is a good learning path for the professional development and a good learning forum, as the participants are in different phases in digitalization and carrying out online courses. We also found out that the participants are interested in the matters, from which they do not benefit themselves. They are willing to act across the institutional boarders in order to gain mutual benefit.

We asked an open question: what is needed for the expert group to have the potential to outlive the time span of the project? The answers were grouped under five main headings:

- Strategic management ‒ the activity becomes a part of the normal activities within all UASs.

- Resources – teachers’ resources to participate in the development nationally

- Clear aims and an action plan for the activity – a responsible party for the group

- Contacts – contacts both online and F2F

- Environment – a user-friendly platform

To summarize, certain characteristics of the participants, such as enthusiasm and openness for new things are prevalent in the present expertise group. The participants are also apt to work for mutual benefit. We also found out that certain characteristics of the group seem to be crucial if we expect the group to outlive the time span of the project itself. Such characteristics are, for example, strategic management, clear aims and responsibility of the group, as well as a user-friendly environment. These features coincide partly with the principles for cultivating COIs. The results provide a framework to further study these principles and how they are prevalent in the group that continues to grow during the project.

Conclusion and further studies

To answer to our main question in the beginning of this article, we think that it is possible to find characteristics of the participants or features of an expert group, which support the cooperation to outlive the time span of a project. The eAMK project has developed a loose e-learning community of experts in UASs and the network has grown through webinars and seminars carried out in the eAMK project. We have also found some characteristics that can help to further study the Principles for Cultivating Communities of Practice and how the experts group will outlive the project.

The Future results may help us to understand what kind of challenges are involved in the cooperation of HIEs. As we know that the drivers for the change come from the surrounding society, the modelling of a new practice for HIE is necessary. Strategic networks are needed as well as communication and new kind of communities of practice. These can help the support HEI for innovations while keeping mind that it is people who make the connections, not the structures.

Authors

Minna Scheinin, Lic. Phil., MA(ODE), Head of Future Learning Design, Turku University of Applied Sciences, minna.scheinin(at)turkuamk.fi

Mauri Kantola, MA, Senior Advisor, Turku University of Applied Sciences, mauri.kantola(at)turkuamk.fi

[vc_tta_accordion active_section=”0″ no_fill=”true” el_class=”lahteet”][vc_tta_section title=”References” tab_id=”1458134585005-b3f22396-5506″]

COM (2017). Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. https://ec.europa.eu/education/sites/education/files/he-com-2017-247_en.pdf. Retrieved 25. August 2018.

Kantola, M., Kettunen, J. & Helmi, S. (2010). Strategic regional networks in higher education. In Regional Innovation Systems and Sustainable Development: Emerging Technologies. Information Science Reference. Hershey and New York.

Konst, T. & Kairisto-Mertanen L. (2018). Innovation Pedagogy. Preparing Higher Education Institutions for Future Challenges. Suomen yliopistopaino – Juvenes Print. Tampere.

Mulgan, Geoff (2018). Big Mind, How Collective Intelligence Can Change Our World. Princeton University Press, Princeton and Oxford.

OKM (2018). Korkeakoulutuksen ja –tutkimuksen visio 2030, http://minedu.fi/korkeakoulutuksen-ja-tutkimuksen-visio-2030. Retrieved 26 January 2018.

Ordóñez de Pablos, P., Lee, W.B. & Zhao, Jingyuan (eds.) (2010). Regional Innovation Systems and Sustainable Development: Emerging Technologies. Information Science Reference. Hershey and New York.

Palonen, T., Lehtinen, E. & Hakkarainen K. (2017). Asiantuntijuuden kehittyminen ja tieteenalan jäseneksi kasvaminen. Teoksessa: Murtonen, M. Opettajana yliopistolla. Korkeakoulupedagogiikan perusteet. Vastapaino. Tampere.

Scheinin, M., Kantola, M. & Simola, S. (2017). Yhteisen opintotarjonnan kehittäminen ammatillisia rajoja rikkovaksi avoimeksi verkkotutkinnoksi – mahdollisuuksia ja haasteita. http://www.eamk.fi/fi/digipolytys/yhteisen-opintotarjonnan-kehittaminen

Retrieved 30 April 2018.

Wenger,E., McDermott,R. &Snyder, W.M. (2002). A Guide to Managing Knowledge. Cultivating Communities of Practice. Harvard Business School Press. Boston. Massaschussetts.

Williams, J. (2017) Public Policies for Collaboration, Alliance, and Merger among higher Education Institutions, OECD Working Paper No 160 – forthcoming; https://minedu.fi/documents/1410845/4177242/EDU-WKP-2017-9.pdf/e3d72fd4-fcae-41d4-b8eb-87760435fa4d/EDU-WKP-2017-9.pdf.pdf. Retrieved 26.9.2018.

[/vc_tta_section][/vc_tta_accordion]