Suvi Kiviniemi

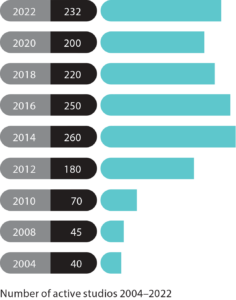

The number of game studios in Finland went down for years. So much so that those developing the local ecosystem were getting worried – including us at Metropolia UAS’s Turbiini campus incubation, since supporting the early steps of game studios is one of our areas of expertise. But now, for the first time in years, we are back on the rise. Between 2014–2020, the number of active studios dropped from 260 to 200, but in 2022, it was back up to 232 (Neogames 2023, 13; Figure 1).

The rise is slower than between 2010–2014, but that isn’t necessarily negative. Many of the studios established during those years, soon after the initial success of Supercell and Rovio, were built on unrealistic expectations of fast success.

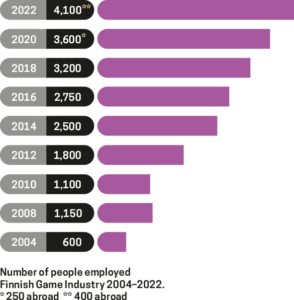

While the number of active studios is still slightly lower than 10 years ago, employment and turnover tell a different story. Between 2014 and 2020, the number of employees went up by 44%, and turnover by 78% (Neogames 2023, 21–25; Figure 2). The Finnish game industry is maturing; the vast majority of revenue and jobs are created by a minority of studios.

A maturing industry needs a healthy grassroots level. As Neogames points out, startups are better equipped to adapt quickly and take advantage of emerging opportunities than large studios (2023, 30). The innovative approach of startups is crucial to keep the industry resilient. A healthy ecosystem also has a balanced mix of first- and second-time founders. While first-timers’ studios are rarely successful, they lay down important learnings for a second round. And even for those who later become employees for other studios, starting their own is a learning experience like no other, as long as they don’t end up burned out or in debt.

In early 2023, Turbiini’s game program, LGIN, ran a survey aimed at fresh and future Finnish game industry professionals to map their attitudes towards entrepreneurship. The goal of the survey was to understand which factors make entrepreneurship attractive for them, and which undermine their will to set up their own studios.

Respondent profile

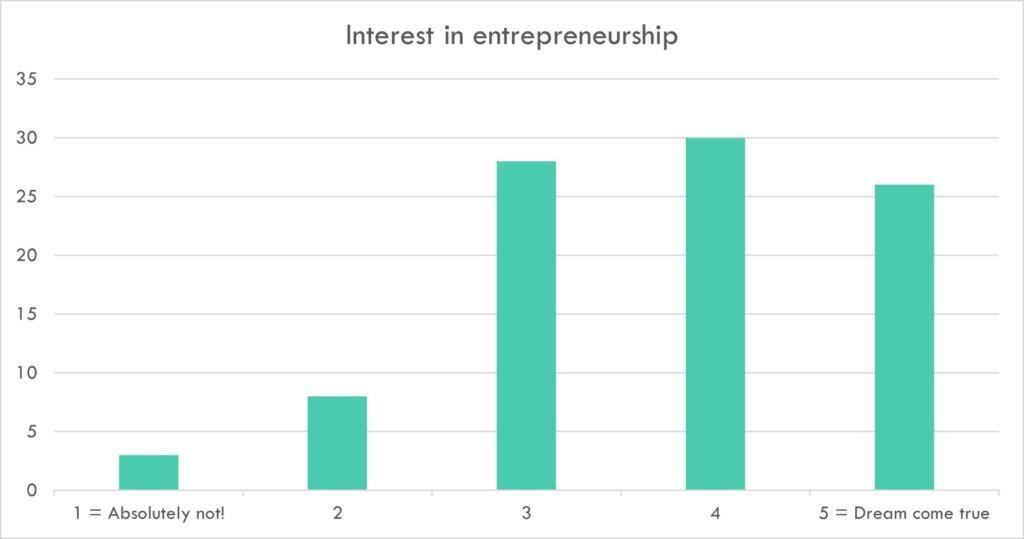

The vast majority, 92 out of 95 respondents, were in Finland. Their interest towards entrepreneurship was relatively high; the most commonly selected option was 4 on a scale from 1-5, where 1 was labeled as ”absolutely not”, and 5 as ”dream come true” (Figure 3). This result is not likely to represent the industry as a whole; people with higher interest in entrepreneurship are more likely to respond to a survey about it.

Most of the respondents (63 %) were students. Many were hobbyist developers (21 %), indie developers without a company (13 %), indie developers with a company (8 %), or startup founders or entrepreneurs (12 %). Only 16 % of the respondents were currently employed in the industry.

A clear majority of respondents were new to games as a profession; 70 % had 0-2 years of industry experience, and 13 % 3-5 years. Yet, there were some with even 10+ years of experience.

What makes game entrepreneurship attractive?

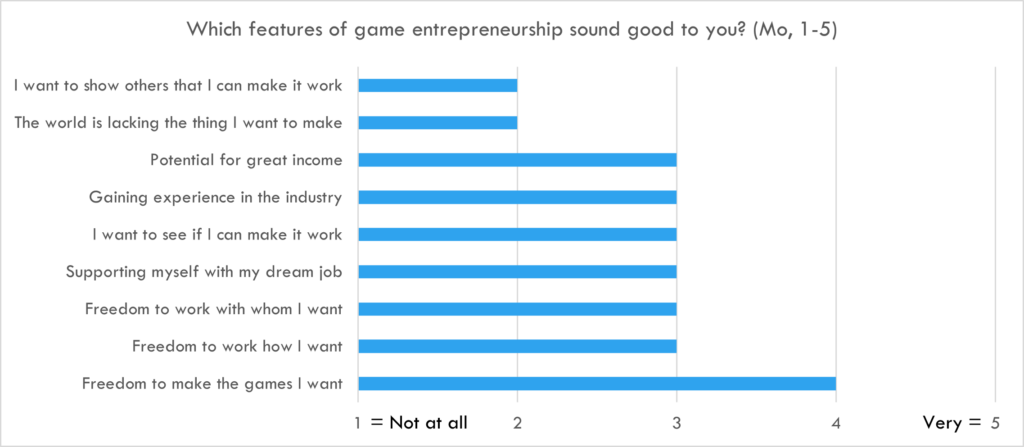

What makes setting up a studio attractive for the respondents? The survey had 9 response options for “which features of game entrepreneurship sound good to you?”. The respondents rated them on a scale from 1 to 5, where 1 was ”not at all” and 5 ”very”. The top four responses speak clear language; they were ”freedom to make the games I want” (Mo 4), ”freedom to work how I want” (3), ”freedom to work with whom I want” (3), and ”supporting myself with my dream job” (3). The respondents appreciate independence and agency and crave creative freedom.

Learning by doing, craving challenge, and financial stability were also popular options; both ”I want to see if I can make it work”, ”gaining experience in the industry”, and ”potential for great income” had a mode of 3. The least popular responses were ”the world is lacking the thing I want to make” (2), and ”I want to show others I can make it work” (2). The respondents seem to be highly internally motivated, and find less motivation in external factors, such as status. (Figure 4)

An open field prompt ”Something else that makes game entrepreneurship interesting for you?” gathered 20 responses, which were then categorized by the theme of their content. The most common theme (6 responses) was doing things that matter and leaving a mark. The second (4 responses) was potential for innovation and craving for challenge.

”I’d like to see if it’s possible to become a somewhat successful indie game developer and a potential employer for those people who are currently struggling to unleash their full potential – be it struggles with mental health or lacking the confidence or opportunities to pursue what they truly want to do. It won’t bring home millions, but maybe it could be made sustainable enough to do something that matters.”

Stoppers of game entrepreneurship

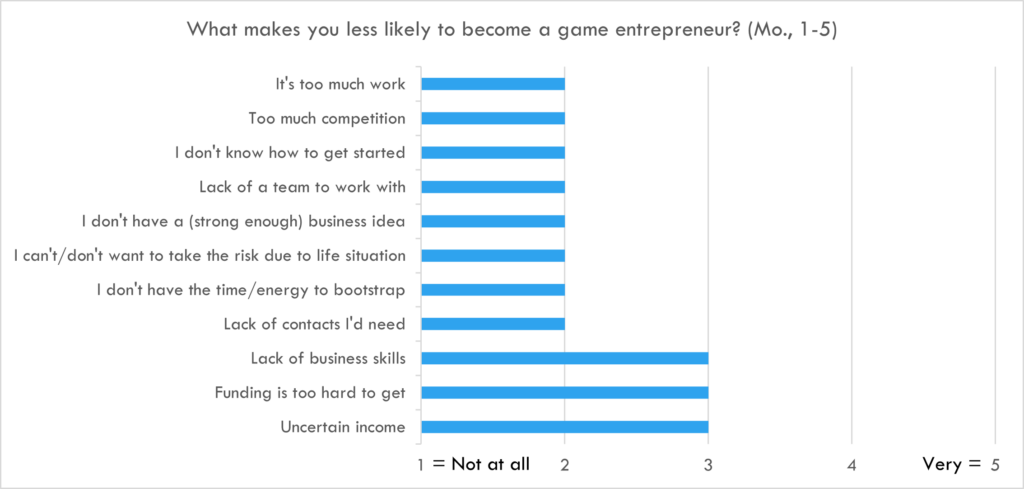

“What makes you less likely to become a game entrepreneur?” had 11 response options. The highest fervencies had the following options: ”uncertain income” (Mo 3), and ”funding is too hard to get” (3), and ”lack of business skills” (3). Financial uncertainty and lack of knowledge in business is the main reason the respondents will not start a game studio.

At the tail end of options, each with a mode of 2, were other business-related challenges – ”lack of contacts I’d need”, and ”I don’t have a strong enough business idea” – or personal life situations – ”I don’t have the time/energy to bootstrap” and ”I can’t/don’t want to take the risk due to life situation”. Similarly, at mode 2, were ”lack of team to work with”, ”I don’t know how to get started”, and ”too much competition”, and ”it’s too much work” – the respondents are willing to find their teams, face the competition, and work hard towards their dreams. (Figure 5)

The open field prompt ”something else that makes you less interested in game entrepreneurship?” gathered 26 responses, which were hard to classify, due to a lot of variation and highly emotional content. However, 4 responses were mainly about self-doubt, and many others touched upon it. Building up the confidence to start a studio, especially as a junior, can be overwhelmingly hard.

”Creative sector in general requires a great deal of vision and self-confidence – and those are sometimes extremely hard to maintain.”

At the end of the survey, there was an open field prompt ”Free word! Want to say something that doesn’t fit in the other questions?” 14 respondents took the opportunity, their responses varying from brief thank-yous to over a hundred-word commentaries on the state of the game industry, risks of entrepreneurship, or even critique of the current financial system. The responses made it clear that the young people of the industry are hard-working and passionate towards their craft, but often feel their success is not in their own hands.

”The Global economy is unforgiving and cruel to most entrepreneurs, and I don’t really want to be subject to its whims. I don’t think I have the mental fortitude to risk getting crushed by its weight, although no one is really safe from that anyway.”

Conclusions

The young, entrepreneurial talent of games craves meaningful work, creative freedom, and interesting challenges. They are intrinsically motivated and see potential for innovation in the industry and its technologies. They also see entrepreneurship as a potential path to the careers they want to build.

Simultaneously, they worry about financial uncertainty in a highly competitive market, know they don’t yet have the business knowledge they need to start their own studio, and often cannot bootstrap – i.e. work on their studio for long periods of time without pay, or alongside a full-time job – due to their situation in life.

The respondents’ worries are realistic. Finding a profitable business in games usually takes years, and there is little early-stage funding available in Finland; in practice, Avek’s Digidemo grants – concept 5000€, demo 10 000€ or 20 000€ (Avek 2023) – are often the only option for those without an investor or their own money, and neither is likely for industry juniors. 20 000€ does not take you far; even a small game typically takes several months’ worth of full-time work by a team of professionals. Not to mention that one game is unlikely to get a studio to the point of any meaningful income.

Granted, it is no-one’s responsibility to finance an entrepreneur’s dreams. Still, it is a fact that in Finland, the current social security system strongly discourages starting new companies in industries in which becoming profitable takes years. For many, the only option is starting a company while being employed elsewhere, which is a big personal risk; a job can always be lost. Unemployment benefits are theoretically possible, but in practice notoriously hard to get if you own a significant part of a company, even if the company is not active and has never had any significant income. The Startup Grant (roughly 700 €/month), which is meant to support becoming a full-time entrepreneur, is capped at one year (KEHA Centre 2024).

Often, the smartest way for game teams is to not risk their access to social security by setting up a studio, and instead keep the project as a hobby on the side of a full-time job. This means that the ownership of the project is often unclear, and any income or a member of the team leaving makes things complicated.

And yet, the number of new studios is on the rise, and many people are excited to start new projects, eager to learn the ropes. It is heartbreaking to know how big the risks they need to take are. When there is little early-stage funding available, and social security structures punish entrepreneurs in industries where getting to profitability typically takes years, many personal risks are unavoidable.

Situations like this pose ethical questions for incubation programs. Should we still encourage young people to set up companies, or would they be better off keeping their hard work as a hobby, on the side of a full-time job?

Suvi Kiviniemi, B.A.Sc., Specialist, Metropolia University of Applied Sciences, suvi.kiviniemi(at)metropolia.fi.

References

KEHA Centre 2024. Start-up grant – support for a new entrepreneur. Available: https://tyomarkkinatori.fi/en/services/af2667af-e1b5-43dd-9b46-5e49ad1b1c9c/starttiraha—aloittavan-yrittajan-tuki

Kopiosto 2023. Creademo and Digidemo. Available: https://www.kopiosto.fi/en/AVEK/funding/avek-grants-and-support-guidelines/creademo-digidemo/.

Neogames 2023. The Game Industry of Finland Report 2022. Available: https://neogames.fi/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/FGIR2022report.pdf.