I. Introduction

In this article, we identify the basic concepts informing multiprofessional competencies in arts and social work/care, focusing on their specific cultural contextualisation, as framed within the currently running project MOMU (Moving towards Multiprofessional Work in Art and Social Work) funded by the Erasmus+ Programme.[1] In short, the project aims to define competencies in teamwork and enhance educational/teacher knowledge and skills in arts and social work/care (MPW) by developing learning materials and handbooks in this area and embedding this in undergraduate HE provision. It builds on the work carried out in the project MIMO – Moving In, Moving On! which established and embedded the initial methods for MPW into professional practice in Finland and Estonia[2]. (TUAS, 2013)

The emphasis of this kind of MPW work lies in combining the strengths of different arts and social work/care professionals to work effectively together with individuals or communities to address the identified needs. It is a multiprofessional practice stemming from a multidisciplinary approach to working with communities and individuals.

This article will thus aim to a) articulate the cultural and critical contexts of relevant concepts and b) propose overarching criteria for learning frameworks which inform future training modules in the area of MPW.

II. Scope and context

As the initial project documentation suggests, there are ‘artists who are willing to work in new kinds of environments. In the field of social work there is a growing willingness to apply art, but it is not always easy when different professional cultures confront’. (Tonteri, 2013) Artists and arts professionals might feel that they cannot get inside the community of social work professionals or might perceive that by doing so, they leave their artistic integrity behind or open themselves to risks. Social Work/Care professionals, on the other hand, often feel that collaboration may make their work more complicated, and there is often a lack of confidence in applying artistically informed approaches. More often than not, although there is real enthusiasm and willingness, they do not perceive themselves as artists, and do not feel they have the credibility or confidence to use artistic methods. Art is perceived to be associated with a deeply informed, embodied and/or studied practice and thus represents a barrier towards a wider, or deeper application of arts-based approaches in social work/care contexts.

There are plenty of case studies and projects demonstrating on the one hand the positive impacts of art-based working with youth and ethnic minorities (and other communities), and on the other the effectiveness of multiprofessional approaches in health and social care (Glasby, 2007). This project builds on these and various premises that have been widely explored in other publications and embedded into policies and professional practices but focuses on joining these two specific areas of professional practice. For sake of clarity, the basic premises that underpin this work are listed below, provided with a few key recent publications supporting their assertions:

- Arts and culture engagement maximises social well-being and a nation’s productivity

(Carnwath & Brown, 2014; Daykin & Joss, 2016; Sacco, 2011; The National Youth Agency UK, 2009; The Finnish Ministry of Education and Culture‘s Child and Youth Policy Programme 2012–2015; The (Finnish) Art and Culture for Well-being 2010-2014; The Spanish National Strategy ‘Culture for all’; etc) - Multiprofessional working environments are a key component of modern healthcare/social care and policies dealing with children, young people and adults have already accepted/embedded the need to work with multiprofessional approaches as an effective means to achieve impact

(Barr, 1996; Lewitt, Cross, Sheward, & Beirne, 2015; The Scottish Government, 2012a, 2012b; Zwarenstein, Goldman, & Reeves, 2009; EU Youth Report 2012; The Spanish National Strategy on Disability 2012-2020; Government Green Paper entitled ‘Every Child Matters’; Children Act in the UK; etc) - Integrating both arts-based approaches and multiprofessional working methods within young people benefits growth, well-being and participation of young people (Krappe & Leino, 2013; Krappe, Parkkinen, & Tonteri, 2012; Leino, 2012; Tonteri et al., 2013; TUAS, 2013)

These underpinnings need to be inherent in any learning frameworks training young professionals in MPW in social care/work and art, allowing professionals not to lose sight of the need to be effective advocators of the connections between arts and society. The given basis that arts and culture engagement maximises social well-being and a nation’s productivity already appears in various policies, but what is often missing are more formal learning frameworks that help afford professionals to gain the skills, knowledge and competencies needed for effective MPW work to address the challenges of young people in our societies today. Additionally, learning frameworks will need to be able to address the cultural and national contexts of communities, welfare and political institutions as well as learning organisations.

This is where multiprofessional approaches can provide solutions by using the full depth of artistic engagement, while maintaining the community focused support specific to the needs and requirements of the social context. Examples of multiprofessional teamwork by arts and social work/care professionals already exist extensively, but there is a lack of learning frameworks that allow MPW teams to be supported by a structured process of negotiating roles and understanding their own responsibility in this collaborative process.

III. Linking arts-based methods and multiprofessional work

The concepts informing multiprofessional collaboration are widely used, but not often specifically defined in the context of arts and social work/care. Either they cover MPW education (or IPE – Interprofessional Education) (Davis & Smith, 2012; Lewitt et al., 2015), or they consider arts-based approaches in social work without the MPW element.

Within the context of multiprofessional work in arts and social care/work, we define MPW as a collaborative practice stemming from an inherently multidisciplinary approach to working with communities and individuals. Its strength lies in combining the knowledges and skills of arts and social work/care professionals to work effectively together to address the identified needs.

Reappearing themes from prior projects, as well as the general literature, point towards the need to consider integrating supportive measures to address these. These recurrent themes include:

a) From practical, conceptual to organisational dimensions

MPW education does not stand in isolation, and like any multidisciplinary or newly emerging practice, the various dimensions in which it exists tend to become important when advocating for its efficacy. When considering degree level training and knowledge acquisition within universities, multi- and interdisciplinary practices are always influenced by various dimensions, including:

- the academic – multidisciplinary curricula and degree structures

- the organisational – institutional infrastructure for multiprofessional practice

- the social – disciplines underpinning professional practices are elementally social constructs (Boehm, 2007)

Parna referring to specifically MPW work (in Krappe & Leino, 2013) has similar divisions, from organisational, conceptual to practical. These different spheres continuously interact and need to be constantly negotiated in order to ensure that MPW can be embedded both in educational curricula, experiential learning or placement activities, as well as professional practice.

Thus as with any innovative learning practice, it will be of interest to academics and practitioners working in this field to ensure that we have the evidence to prove its efficacy in order to devise learning components that fit into existing organisational structures. Persuasive cases need to be made for the various organisational structures in order to allow effective MPW learning to happen, such as supporting multiprofessional team teaching; co-teaching of multidisciplinary students cohorts.

Outcome measurement thus becomes a necessity in order to afford the organisational dimensions to meet the needs at the theoretical and practical level. In a similar manner, how to measure the individual/pair impact of embedding MPW in professional practice interventions is a subject matter that needs to be integrated into educational provision. And as Carpenter (2005) identifies, outcomes can be at a number of different levels; about learner’s reactions, modification in attitudes and perceptions, acquisition of knowledge, changes in behaviour, changes in organizational practice and benefits to service users and carers.

b) MPW caught in the vocational vs academic debate

To understand and advocate effectively the facilitation of university-based learning environments for multiprofessional practice, it also helps to understand the question of multi-, inter-, and transdisciplinary knowledge creation in universities including their historical evolution that have widely influenced organisational structures.

Depth of knowledge has not always been prioritized over breadth, and the organisational challenges to mind the gaps between what is considered academic and what vocational; intellectual vs professional learning experiences; all these still stem from a 19th century model of intelligence. Certain subjects have come to be perceived as academic only since the 18th century and were reinforced as being ‘academic’ by the rise of the Humboldtian model of a university, which was accepted by most European and American universities. That the English and Scottish (and Irish) ancient universities have more recognisable remnants of their medieval origins may in some way also explain the wider acceptance of the ‘practice-based’ in British university contexts, as exemplified by music composition, drama, dance or creative writing. Whereas in the UK composition is taught in research-intensive universities, in Germany it is predominantly taught in conservatories and music colleges. Similarly, the Finnish HE system still displays a binary divide with universities on the one hand, and universities of applied science on the other, the latter usually not providing study to PhD level. Spanish universities are more and more adopting practice-based methods, however there are still clear differences between University degrees and ‘upper degree professional studies’ (‘formacion professional de grado superior’) which are the equivalent of Universities of Applied Sciences in Finland. Arts Schools in Spain also fall into this category[3]. Even in the UK, where the Further and Higher Education Act of 1992 placed the former polytechnics – with their more vocational and practice-based cultures – into the same framework as the old universities with their perceived predominantly academic provisions, the binary divide is still apparent and its value system perniciously remains, for example in the form of perceived research intensity.

As many of our modern European and US universities are built upon just this Humboldtian ideal of knowledge and intellect, some have argued (Boehm, 2007; Robinson, 2010) that this poses a challenge to our education systems, as well as to our means for knowledge production. The perceived difference between the ‘vocational’ and the ‘academic’ is based on this very specific intellectual model of the mind: that our perception of what academic study entails was formed at a time where the concept of intelligence was limited to the ability to reason deductively. Robinson (2010) sees this divide as being detrimentally influential in the secondary educational sector, but also suggests in his keynote speech to the RSA in 2010 that we need to scrap the perceived dichotomy between the ‘academic’ and the ‘non-academic’, the ‘theoretical’ and the ‘practical’. ‘We should see it as what it is: a Myth’.

The scale and quality of adoption by universities of innovative professional practices, such as MPW in arts and social care, is affected and influenced by these contexts, and in turn affects the creation of the skills and competencies needed for multiprofessional work, and this has been repeatedly identified in the general MPW literature reaching back at least 40 years (see Lewitt 2015). For MPW work to be widely accepted in the HE sector, these national and international Higher Education policy drivers will need to be understood to devise convincing cases for adoption.

c) Multidisciplinary knowledge and multiprofessional practice

As multiprofessional work is based on multidisciplinary learning, research and practice, as indicated above, how we facilitate interdisciplinary and multidisciplinary learning in Higher Education becomes an important framework consideration. As part of this, knowledge institutions need to understand the nuances in relation to interdisciplinary knowledge. Thus apart from above structural dimensions, it also helps to see disciplinarity as an umbrella concept with individual terms referring to various nuances. According to Stember (Stember in Seipel, 2005) we can differentiate between knowledge formation in the following categories:

Intradisciplinary enquiries, which involve mainly one single discipline, such as a musician harmonically analysing a piece of music, or a social scientist using thematic analysis of structured interviews to consider important aspects of self-expressions of particular communities,

Cross-disciplinary enquiries tend to view one discipline from the perspective of another, such as understanding the history and social dynamic of British Pop Bands through Tajfels (1982) social identity models,

Transdisciplinary enquiries, in Stember’s words, are ‘concerned with the unity of intellectual frameworks beyond the disciplinary perspectives’. Seipel goes on to suggest that they may deal with philosophical questions about the nature of reality or the nature of knowledge systems that transcend disciplines.

Multidisciplinary enquiries draw on the knowledge domains of several disciplines, providing different perspectives on one enquiry in an additive fashion. ‘In multidisciplinary analysis, each discipline makes a contribution to the overall understanding of the issue.’ In this, a study of music performance can include insights derived from psychology as well as historical performance practice.

Interdisciplinary enquiries require ‘integration of knowledge from the disciplines being brought to bear on an issue. Disciplinary knowledge, concepts, tools, and rules of investigation are considered, contrasted, and combined in such a way that the resulting understanding is greater than simply the sum of its disciplinary parts. However, the focus on integration should not imply that the outcome of interdisciplinary analysis will always be a neat, tidy solution in which all contradictions between the alternative disciplines are resolved. Interdisciplinary study may indeed be ‘messy’. However, contradictory conclusions and accompanying tensions between disciplines may not only provide a fuller understanding, but could be seen as a healthy symptom of interdisciplinarity. Analysis which works through these tensions and contradictions between disciplinary systems of knowledge with the goal of synthesis—the creation of new knowledge—often characterises the richest interdisciplinary work.’ (Seipel in Boehm 2014)

Multiprofessional practices can thus be seen as the professional application of a knowledge domain that derives from multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary methods of enquiry. These multidisciplinary approaches will be facilitated by the educational frameworks developed by the current MOMU project. What will undoubtedly emerge is also genuine interdisciplinary knowledge and practice, where the result becomes more than merely the sum of the parts. This ‘interdisciplinary’ stage, represented by the synergy of different knowledge domains can conceptually be seen as the evolutionary development of disciplines and their associated professional practices (C. Boehm, 2007). However, it should be noted that multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary practices often exist simultaneously in a field, providing in the extreme both the opportunities of synergy of something new on the one hand, and an addition of existing deep knowledge on the other. This represents a rich environment in which new knowledge and its associated practices are formed for real-world challenges that our contemporary society is facing. MPW work thus adds a new knowledge and professional practice that will hopefully allow us to meet some of the challenges of today’s world.

d) Sharing competencies and capturing change: communication and documentation

Whether choosing a multiprofessional practice, or an interdisciplinary one, the process of formation of collectively shared competencies needs an intentional effort to communicate from one knowledge/practice domain to the other, from one expert/practitioner to the other. Structured communication channels are thus a key element in the toolset of any MPW practitioner.

Leino (2012), writing on the experiences of working in MPW teams as part of the MIMO project, emphasises the shift towards having to manage a collaborative owned knowledge: ‘The traditional concept of expertise is based on emphasizing the individual’s professional skill, which was seen to arise from the individual’s experience of working in the field in question.(…) Collective expertise means a shared kind of competence.’(Leino, 2012)

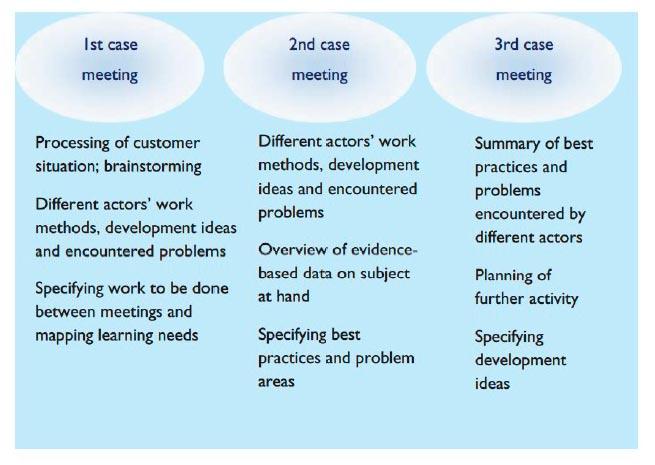

To facilitate this process of managing a shared collection of competencies, the MIMO project put forward the model below, which acted as a tool for learning, development and MPW work supervision (see Figure 1) and encompasses a concept of collective expertise through teamwork, thus facilitating the sharing of competencies between professionals from different fields (Leino 2012).

Thus central to the notion of collectively shared competencies and collective expertise development is the need to have structured communication channels available that support the sharing and combining of different knowledge and values. Communication becomes a vital part, specifically as different professional cultures will not have the same terminologies and concepts or have similar terms and concepts which mean different things whilst also having differing working methods and processes.

Besides the need to maintain structured communication channels to facilitate a process of experienced change, there is also the need to document just this process. Art and social work/care is known to allow and support transformational change, be it of perspective, personal boundaries, self-knowledge and reflection, personal or community identity, empathy or empowerment. However when working in MPW it is useful to ensure that teams are aware that the focus is often predominantly on the process rather than the product. So although artistic integrity and ‘depth’ is needed and even desired, the social contexts requires an artistic experience to provide some form of transformation or change through a process of engaging artistically or creatively. ‘Rather than the artistic end product, the most important aspect of the work was the process by which the opportunities (were) awarded by art’.(Leino 2012)

It might be worthwhile noting, that this emphasis on the creative process, rather than the creative artefact (or end product), as an inherent element of an artistic practice, differs from country to country. Music, as one of the most ‘ancient’ academic subjects has had the least resistance in being accepted as an academic study to PhD level in Universities in UK. But specifically those countries that were at the forefront of artistic subjects being accepted in academic contexts, e.g. those countries in which it has been possible to study Dance, Drama, Theatre and Creative Writing to PhD level, pushed forward the idea of practice-as-research, or PaR. ‘PaR acknowledges the significance of a direct engagement from within the practical activity as an integral part. What is often called a dialogical relationship between the practice on the one hand, and the conceptual and critical frameworks on the other, is integral to PaR. In this, it does have resemblances to methodologies such as action research.’ (Boehm, 2014) With the need for an ongoing dialogue as part of a rigorous, research informed practice, in short ‘praxis’, documentation becomes an integral part of that practice. And this in turn reflects similar good practices identified in the social work/care context. Here, McLaughlin (McLaughlin, 2012) has argued that practitioners should view their practice as research in action whereby they should evaluate their interventions and where practice should inform research and research should inform practice. But the national differences in this area of artistic ‘praxis’ does have ramifications for MPW in that documentation as part of a professional practice might be common knowledge for social work/care professionals, but might not be as inherently understood by all arts professionals. With a focus on the – by its nature – ephemeral process, it follows that documenting practice also becomes a vital part of MPW work and needs to be considered as part of the competency frameworks.

e) MPW learning improves adoption of MPW methods

Most literature about MPW in healthcare reflects the MOMU philosophy of the experiential value of learning with multiprofessional cohorts of students, and being facilitated to learn by multiprofessional teams of educators. Whether these learning experiences are labelled as interdisciplinary or interprofessional, intra-professional or interdisciplinary-interprofessional (Wiezorek, Sawyer, Serafini, Scott, Finochio in (Wiezorek, Sawyer, Serafini, Scott, Finochio in Lewitt et al., 2015), the underlying plausible assertion is that learning together will lead to an embodied understanding of how to better work together. Part of this is the premise that collaboration is itself a skill-based social process, and thus early experiences of MPW as part of skills and knowledge acquisition is vital. (Clark, 2006; Oandasan & Reeves, 2005a, 2005b)

It is noteworthy that MPW in healthcare is usually with people who are employed by the same employer, work in the same structures and share a common language. This is different from social work/social care and arts professional who are usually employed by different employers who may irregularly come together and have to develop a common language.

To support individual learners develop the team-working skills and competencies, mentoring (Lewitt et al., 2015), peer-led reviewing, peer-mentoring, experiential learning and placement shadowing (Lewitt et al., 2015) all have been identified as effective. Although no empirical study of the efficacy have been carried out, considering the very individualised and specifically contextualised needs of arts and social care/work projects, using a leadership-related-coaching approach with real experiential learning in real-life projects can be expected to become one best practice that supports teams on their own experiential journeys.

IV. Terminological quagmires, or building sandcastles with a shovel

The formation of a new knowledge domain and its professional practice arrives often with the formation of new concepts, words and associations. This terminological quagmire is made more complex when considering it across cultural and country boundaries, with their own cultural heritages and associations. Thus the words ‘multiprofessional’, ‘interprofessional’, ‘competency’, ‘applied arts’ might all seem harmless on their own, but when considered in different cultural contexts, the expert trained and practiced in one country faces the helplessness of being caught in a differently flowing maelstrom of concepts and meanings.

These interdependencies do not exist in isolation but are part of a wider political, cultural and social contexts of nations, both helping to shape and be shaped by these concepts. Language and culture thus often not only enlighten us, but make us humble in the acceptance that words are simply crude tools in our sandbox of quite sophisticated concepts, meanings and truths. Thus the communication of this knowledge, our knowledge exchange of which this article is one attempt, necessarily is like building the most intricate of sandcastles with a large shovel.

Thus it might be worthwhile to explore the complexities of certain terms in relation to different critical and cultural frameworks.

In the English language, ‘multiprofessional work’ is one term of many that is increasingly used to define a concept to describe a way of working with different professional sectors or services. Other terms often found relating to this are ‘interprofessional work’ or ‘interagency work’.

Although in MOMU we would normally consider the term to denote a model that necessitates collaborative team-work processes at every stage, in health and social care practices this is not always the case. A ‘consecutive’ working process with case handovers, joint case management, but not necessarily simultaneous collaborative multiprofessional team work, is also often considered to conform to this term, such as is described in various examples in Davis’ pedagogical handbook about multiprofessional work within child services (Davis & Smith, 2012). This might be considered to conform more to the UK-used term of ‘interagency work’, but the fluid and responsive nature of this kind of work and how it moves seamlessly from more linear case handovers to non-linear, simultaneous multi-sector involvement makes it difficult to find one term fitting all specific scenarios and contexts.

Historically, in 1997 the Centre for the Advancement of Interprofessional Education (CAIPE) put forward the definition that ‘interprofessional education occurs when two or more professions learn with, from and about each other to improve collaboration and the quality of care’(CAIPE, 1997).

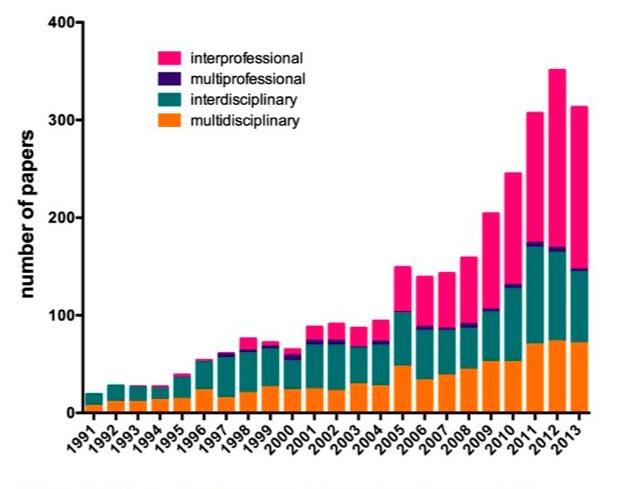

Lewitt (2015) points out that there is a renewed interest in MPW/IPW and they put forward an exponential rise in publications using these terms in key works (See Figure 2). Interestingly they point out that ‘publications using the terms multi–‐ or interdisciplinary tended to be practice–‐oriented, while approximately 50% of papers using the term interprofessional related to undergraduate or postgraduate education.’(Lewitt et al., 2015) The interdisciplinary underpinning stands out for Lewitt, who wrote: ‘There is lack of consensus and clarity around the use of the terms multiprofessional and multidisciplinary, both in the literature and in practice, and they are often used interchangeably.’

The discussion around the concept of ’multiprofessionality’ and ’multiprofessional work’ is highly topical in Finland where the arts sector has not had a long tradition of cross-sectoral cooperation or even ‘community arts’. This can be seen in public and media debates, in the most of extreme of these the concept of a multiprofessional practice was questioned in terms of disciplinary depth, e.g. from an artistic perspective the doubters put forward the danger of risking artistic integrity. The fear is often expressed in these debates that overwhelming demands on arts professionals would be made, being obliged to be multiply skilled persons or multi-taskers; artists who are at the same time therapists, teachers, counsellors, business managers, salespersons, project experts and so on.

The term multiprofessional seems to have gone out of fashion in the UK as Banks (2010, p.281) notes: ‘The idea of “multi-professional working” (different professionals working alongside each other) is being replaced by “interprofessional working” (different professionals working closely together, with shared goals and perhaps with interchangeability of roles).’(Banks, 2010)

Of interest to us are the notions of ‘working closely together’, ‘shared goals’ and ‘interchangeability’ The working closely could involve two or more workers jointly sharing a case or a project and doing everything together to the situation of a key worker coordinating the contributions of other workers to achieve an agreed aim. Shared goals whereby the workers would have jointly assessed a need and agreed a plan building on the strengths of both, or more, workers identifying who would do what. Interchangeability is interesting as it suggests the final destination of interprofessional working for workforce analysts might be to question whether the two workers are always needed or whether we need a new type of professional an interprofessional worker or even a non-professional interprofessional worker.

‘Multiprofessional working’, ‘interprofessional practice’, ‘multi-disciplinary working’ or collaborative practice are often used interchangeably but all contain a notion that by working together their will be a pooling of resources, and where the ‘whole is believed to be greater than the sum of the parts’.

In the UK some social work programmes have had dual professional qualification programmes e.g. learning disability nurse and a social worker. However, even though qualified workers were qualified in both disciplines they found it difficult to obtain jobs which used both their skill sets and instead were forced into joining one profession or the other McLaughlin (McLaughlin, 2012b). This also reminds us that professions are not neutral entities and that professions like social work/social care and the arts are involved in an exercise of occupational boundaries claiming control of their own area of practice. Thus change in one profession’s claims may have knock on effects in others (Abbott, 1988).

In England there are 72 approved social work qualifying programmes in social work who enrol approximately 4,500 students per year (Skills for Care, 2016). As part of the heavily prescriptive curriculum social work students are expected to develop skills in interprofessional practice especially as the failure of the caring professions and the police to work together has been highlighted in all UK child death inquiries since Maria Colwell (1974) to Peter Connolly (Baby P 2007). The Health and Care Professions Council ((HCPC) who currently regulate social work require qualifying and registered social workers as part of their Standards of Proficiency to be able to:

- be able to work in partnership with others, including those working in other agencies and roles (9.6)

- be able to contribute effectively to work undertaken as part of a multi-disciplinary team (9.7) (HCPC, 2012:11)

These standards have to be achieved by all qualifying social workers, but are generally seen in relation to working with education, health services and the police rather than with artists. This is not to say that the arts have not been used in social work, for example in the development of ‘life story books’ for children moving to alternative permanent families or the use of art, poetry, drama or music with people suffering from mental illness or dementia. It is just that artistic approaches have never been mainstreamed within social work education or practice. Hafford-Letchfied, Leaonard and Couchman (2012) in their editorial to a special edition of Social Work Education: The International Journal on the use of arts in social work note that although artistic methods are becoming more common they remain underused, connected to the lack of critical mass of evidence for their effectiveness.

The concepts around the term of MPW have thus various dimensions and contexts in which different sets of meanings and associations, and specifically for this project the professional connotations and the national contexts are relevant in order for consistent, but possibly not conform, methods of MPW education to be established.

V. Conclusion

In this first article as part of the three year EU funded MOMU project, we have explored some of the basic critical and cultural contexts in which multiprofessional work in arts and social care resides. As an inherently multidisciplinary practice, emerging from the more interdisciplinary challenges that our complex societies throw at us, it provides challenges to educational providers that derive their historical and cultural understanding from a modernity point of view of prioritising depth of disciplines. We felt that it was necessary to understand this underpinning before moving on to exploring multi- and interdisciplinary learning frameworks that will train the next generation of professionals working in this area.

Our specific learning frameworks will be the subject of a separate article, but from these explorations it becomes already clear that any learning frameworks put forward will need to cover the following aspects, whose critical and conceptual frameworks have been explored in this article:

a) Art as a basic human right (see section II);

b) Creativity and its connection to health and well-being;

c) Learning components that fit into existing organisational structures, as well as make a persuasive case for multiprofessional teaching teams and co-teaching (see section IIIa);

d) Importance of measuring outcomes of MPW work and MPW learning for demonstrating impact (see section IIIa);

e) Ability to address various national and international policy related drivers (see section IIIb);

f) Understand the academic-vocational divide as a myth, and allow experiential learning (see section IIIb);

g) Appreciation of MPW as the professional application of a knowledge domain that derives from multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary methods of enquiry (see section IIIc);

h) Skills related to communication and documentation are part of the professional practice (see section IIId);

i) MPW learning Is most effective as an MPW practice (see section IIIe);

j) Sensitivity to terminological quagmires and respect the interdisciplinary, interprofessional and intercultural interdependencies of terms and concepts (see section IV).

This is an exciting time for multiprofessional learning, and we expect that there will be many possible approaches taken across Europe to explore how best we can train future professionals. We would hope that the MOMU approach will be one of the models that will meet the challenges. Thus, we have covered in this article the specific cultural and critical contexts and propose frame criteria for learning frameworks which inform and develop future training modules in the area of MPW.

VI. Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the ERASMUS+ programme for funding this project, and everyone within the project team as well as all other individuals that have already been involved in, or contributed to the project in various ways, including interview participants, survey participants, workshop attendees or simply people we meet and talk to. The list goes on. We believe this project, which is interfaced between arts, health and wellbeing, is important, and we are thankful to be working in an area where we meet people on a daily basis that are as passionate about arts and well-being as we are. Thank you.

[1] The idea of the project was developed in cooperation with four European Universities involved intensively in arts and social work provision: Turku University of Applied Sciences (Finland), Manchester Metropolitan University (UK), University of Tartu Viljandi Culture Academy (Estonia) and University of Castilla-La Mancha (Spain).

[2] MIMO was a research and development project running from 2010–2013 funded from the Central Baltic INTERREG IV A 2007–2013 programme, the project developed multiprofessional teamwork models and applied art-based methods for participatory youth work and embedded the approach within its own educational provision and many external youth organisations.

[3] See http://www.escueladeartelapalma.org/ and http://eacuenca.com/ (Last accessed 2016/07/23)

Authors

Carola Boehm, Manchester Metropolitan University, UK; Associate Dean; MA; C.Boehm(at)mmu.ac.uk

Liisa-Maria Lilja-Viherlampi, TUAS, Finland; Principal lecturer I Culture and Well-being; PhD; Liisa-maria.lilja-viherlampi(at)turkuamk.fi

Outi Linnossuo, TUAS, Finland; Senior teacher/Social Worker; PhD; Outi.M.Linnossuo(at)turkuamk.fi

Hugh McLaughlin, Manchester Metropolitan University, UK; Professor; H.McLaughlin(at)mmu.ac.uk

Emilio Jose Gomez Ciriano, Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha, Spain; Professor; EmilioJose.Gomez(at)uclm.es

Oscar Martinez Martin, Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha; Señor Lecturer; oscar.martinez(at)uclm.es

Esther Mercado García, Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha; Associate Professor; esther.mercado(at)uclm.es

Suvi Kivelä, TUAS, Finland; Project manager; suvi.kivela(at)turkuamk.fi

Ivar Männamaa, TÜ Viljandi Kultuuriakadeemia, Estonia; ivarman(at)ut.ee

Jodie Gibson, Manchester Metropolitan University, UK; Director Axis Arts Centre, MSc; J.Gibson(at)mmu.ac.uk

[vc_tta_accordion active_section=”0″ no_fill=”true” el_class=”lahteet”][vc_tta_section title=”References” tab_id=”1458134585005-b3f22396-5506″]

Abbott, A. D. (1988). The system of professions : an essay on the division of expert labor. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Banks, S. (2010). Interprofessional ethics: A developing field? Notes from the Ethics and Social Welfare Conference, Sheffield, UK May, 2010, Ethics and Social Welfare., 4(3), 280–294.

Barr, H. (1996). Interprofessional education in the United Kingdom: Some historical perspectives 1966–‐1996. Supplement to: Creating an Interprofessional Workforce: An Education and Training Framework for Health and Social Care.: Centre for the Advance of Interprofessional Practice and Education.

Boehm, C. (2007). The discipline that never was. Journal for Music, Technology and Education, Vol 1, 2007.

Boehm, C. (2014). A brittle discipline: Music Technology and Third Culture Thinking. In E. Himoinoides & A. King (Eds.), Researching Music, Education, Technology: Critical Insights. Proceedings of the Sempre MET2014 (pp. 51-55). London: University of London.

CAIPE. (1997). Centre for the Advancement of Interprofessional Education (CAIPE), Interprofessional education – a definition. London: CAIPE Bulletin 13, p.19.

Carnwath, J., & Brown, A. (2014). Understanding the Value and Impacts of Cultural Experiences: a Literature Review. Manchester.

Carpenter, J. (2005). Evaluating outcomes in social work education. Scottish Institute for Excellence in Social Work Education (SIESWE) and Social Care Institute for Excellence (SCIE). Dundee and London.

Clark, P. G. (2006). What would a theory of interprofessional education look like? Some suggestions for developing a theoretical framework for teamwork training 1. Journal of interprofessional Care, 20(6), 577-589.

Davis, J. M., & Smith, M. (2012). Working in Multi-professional Contexts: Sage Publications Ltd.

Daykin, N., & Joss, T. (2016). Arts for health and wellbeing: An evaluation framework.

Glasby, J. (2007). Understanding health and social care. Bristol: Policy.

Hafford-Letchfield, T., Leaonard, K., & Couchman, W. (2012). Arts and Extremely Dangerous’: Critical Commentary on the Arts in Social Work Education. Social Work Education: The International Journal, 31(6), 683-690.

HCPC. (2012). Standards of Proficency: Social Workers in England. Retrieved 16/07/2016, from http://www.hcpc-uk.org/assets/documents/10003B08Standardsofproficiency-SocialworkersinEngland.pdf

Krappe, J., & Leino, I. (2013). “A fruitful challenge” – Description of multiprofessional work in the MIMO project. In A. Tonteri, J. Krappe, I. Leino, T. Parkkinen, S. Pyörre & M. Susi (Eds.), MOVING ON! Encounters and Experiences in Arts – Working Multiprofessionally with the Youth. Turku, Finland: Turku University of Applied Science.

Krappe, J., Parkkinen, T., & Tonteri, A. e. (2012). MOVING IN! Art-Based Approaches to Work with the Youth. MIMO Project 2010-2013. (Vol. 127). Turku: Turku University of Applied Science.

Leino, I. (2012). First steps in multiprofeesional teamwork within the MIMO project. In J. Krappe, T. Parkkinen & A. e. Tonteri (Eds.), Moving In! Art-Based Approaches to Work with the Youth (Vol. 127). Turku: Turku University of Applied Science.

Lewitt, M., Cross, B., Sheward, L., & Beirne, P. (2015). Interprofessional Education to Support Collaborative Practice: An Interdisciplinary Approach. Paper presented at the International Conference of the Society for Research into Higher Education 2015.

McLaughlin, H. (2012). Understanding social work research (2nd ed. ed.). London: SAGE.

McLaughlin, H. (2012b). Keeping interprofessional practice honest: fads and critical reflections. In B. Littlechild & R. Smith (Eds.), Inter-professional and Inter-agency Practice in the Human Services: Learning to Work Together (pp. 50–61). Harlow: Pearson Education.

Oandasan, I., & Reeves, S. (2005a). Key elements for interprofessional education. Part 1: the learner, the educator and the learning context. Journal of interprofessional Care, 19(Suppl 1), 21-38.

Oandasan, I., & Reeves, S. (2005b). Key elements for interprofessional education. Part 2: factors, processes and outcomes. Journal of interprofessional Care, 19(Suppl 1), 39-48.

Robinson, K. (2010, 4/2/2010). Changing Education Paradigms. Annual Conference for the Royal Society for Arts, from http://comment.rsablogs.org.uk/2010/10/14/rsa-animate-changing-education-paradigms/

Sacco, P. L. (2011). Culture 3.0: A new perspective for the EU 2014 – 2020 structural funding programming.

Seipel, M. (2005). Interdisciplinarity: An Introduction (Lecture Notes). Retrieved 5/12/2012, from http://mseipel.sites.truman.edu/files/2012/03/Introducing-Interdisciplinarity.pdf

Skills for Care. (2016). Social Work, Leeds: Skills for Care. Leeds.

Tajfel, H. (1982). Social identity and intergroup relations. Cambridge Cambridgeshire; New York, Paris: Cambridge University Press; Editions de la Maison des sciences de l’homme.

The Scottish Government. (2012a). Common core of skills, knowledge & understanding and values for the “children’s workforce” in Scotland: Final common core & discussion questions.

The Scottish Government. (2012b). A guide to Getting it Right For Every Child.

Tonteri, A. (2013). Developing Multiprofessional Working Skills in Art and Social Work.

Tonteri, A., Krappe, J., Leino, I., Parkkinen, T., Pyörre, S., & Susi, M. e. (2013). MOVING ON! Encounters and Experiences in Arts – Working Multiprofessionally with the Youth: MIMO Project 2010–2013. Turku, Finland: Turku University of Applied Science.

TUAS. (2013). MIMO – Moving In, Moving On! Application of Art Based Methods to Social and Youth Work. Retrieved 20/04/2016, 2016, from http://mimo.turkuamk.fi/

Zwarenstein, M., Goldman, J., & Reeves, S. (2009). Interprofessional collaboration: effects of practice–‐based interventions on professional practice and healthcare outcomes.

[/vc_tta_section][/vc_tta_accordion]